Since I started this blog in February 2012, I have written a number of stories about rice genetic resources and their conservation at the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) in the Philippines, one of the centers of the Consultative Group on Agricultural Research (CGIAR).

Since I started this blog in February 2012, I have written a number of stories about rice genetic resources and their conservation at the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) in the Philippines, one of the centers of the Consultative Group on Agricultural Research (CGIAR).

Written over several years, there is inevitably some overlap between the posts. I have now brought them together. Just click on the red boxes below to read each one or expand an image.

I was privileged to manage the International Rice Genebank at IRRI (the IRG, formerly known as the International Rice Germplasm Center or IGRC until 1995) for a decade from July 1991, as Head of the Genetic Resources Center (GRC) [1].

The IRRI campus at Los Baños, 70 km south of Manila. The Brady Laboratory (second from left) houses the genebank cold stores.

There are twelve CGIAR genebanks, and IRRI’s is one of the largest. It’s certainly the oldest. In April, IRRI will celebrate its 65th anniversary [2]. For almost six and a half decades, IRRI has successfully managed the world’s largest collection of rice genetic resources (farmer or landrace varieties, improved varieties, wild rice species, genetic stocks, and the like).

There’s perhaps no crop more important than rice. It’s the staple food of half the world’s population on a daily basis. The genebank is a crucial resource for plant breeders who use the germplasm to sustain and increase agricultural productivity, with the aim of reducing hunger among the world’s poor.

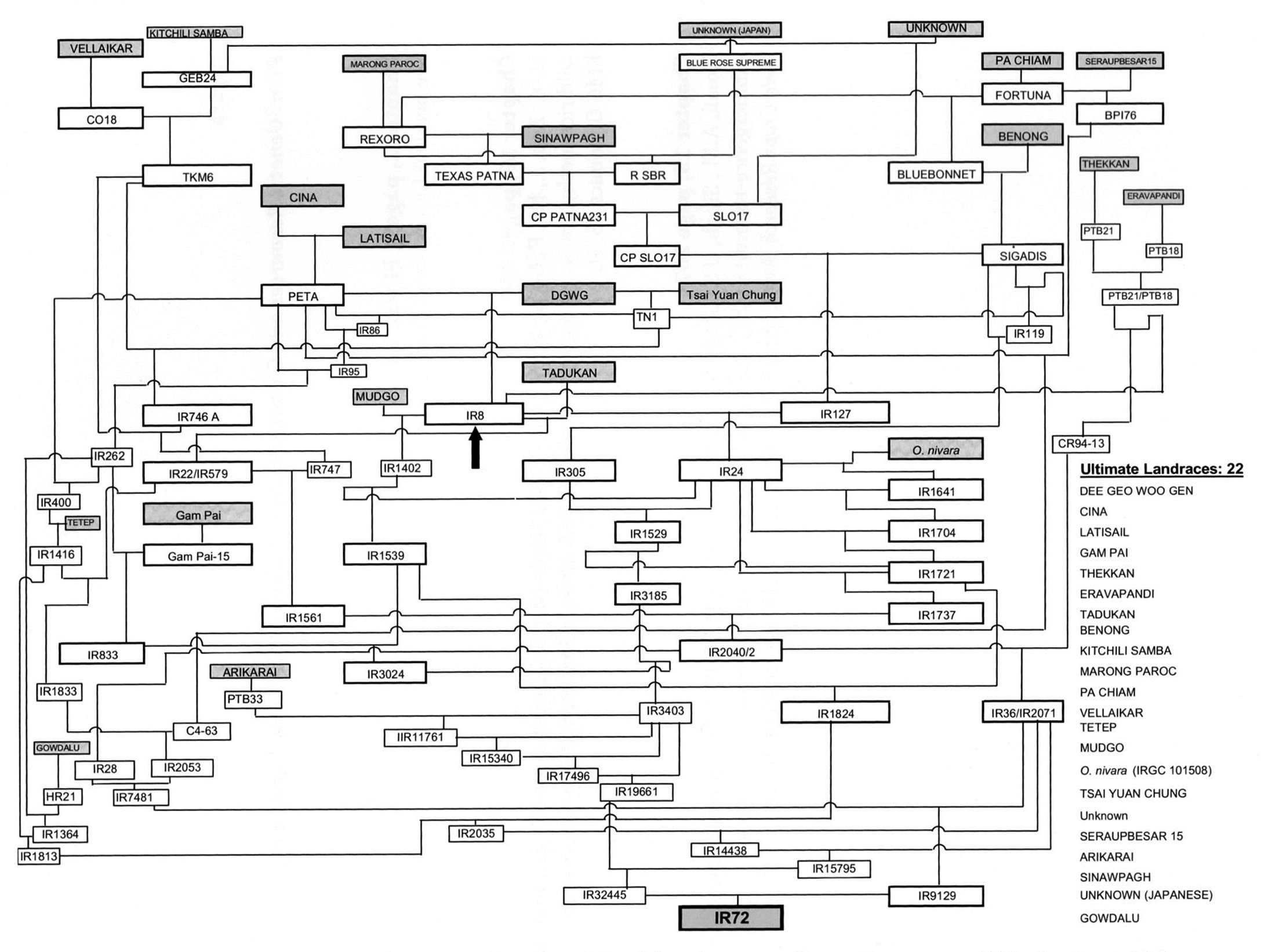

IRRI released the first of the semi-dwarf varieties in the 1960s; many others have followed over the decades, with increasingly more complex pedigrees.

Pedigree of rice variety IR72 showing 22 landraces (boxes with bold lines) and one wild species, Oryza nivara. In contrast, IR8, the first of the widely-grown modern semi-dwarf varieties (indicated by the arrow) had only three landraces in its pedigree.

When I joined IRRI, there were just over 70,000 seed samples (or accessions as they are known in genebank parlance) in the genebank.

During the 1990s, the collection grew by about 30% to a little over 100,000 accessions. This was quite remarkable in itself, given that the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) had come into effect in 1992, and for for at least a decade or more thereafter, many countries were reluctant to share their national germplasm until benefit-sharing mechanisms had been worked out. It says a lot about the mutual respect between national programs (particularly in Asia) and IRRI that we were able to mount a significant program to collect rice varieties and wild species. But more on that later.

During the 1990s, the collection grew by about 30% to a little over 100,000 accessions. This was quite remarkable in itself, given that the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) had come into effect in 1992, and for for at least a decade or more thereafter, many countries were reluctant to share their national germplasm until benefit-sharing mechanisms had been worked out. It says a lot about the mutual respect between national programs (particularly in Asia) and IRRI that we were able to mount a significant program to collect rice varieties and wild species. But more on that later.

Today the collection is approaching 135,000 accessions, safely duplicated in the Svalbard Global Seed Vault (SGSV, under the auspices of the Government of Norway and the Crop Trust). Prior to 1991, and for at least the next decade or more, duplicates samples were also held in so-called ‘black box’ storage at the National Laboratory for Genetic Resources Preservation in Fort Collins, Colorado. I’m not sure whether IRRI has continued its arrangement with Fort Collins now that the SGSV is open.

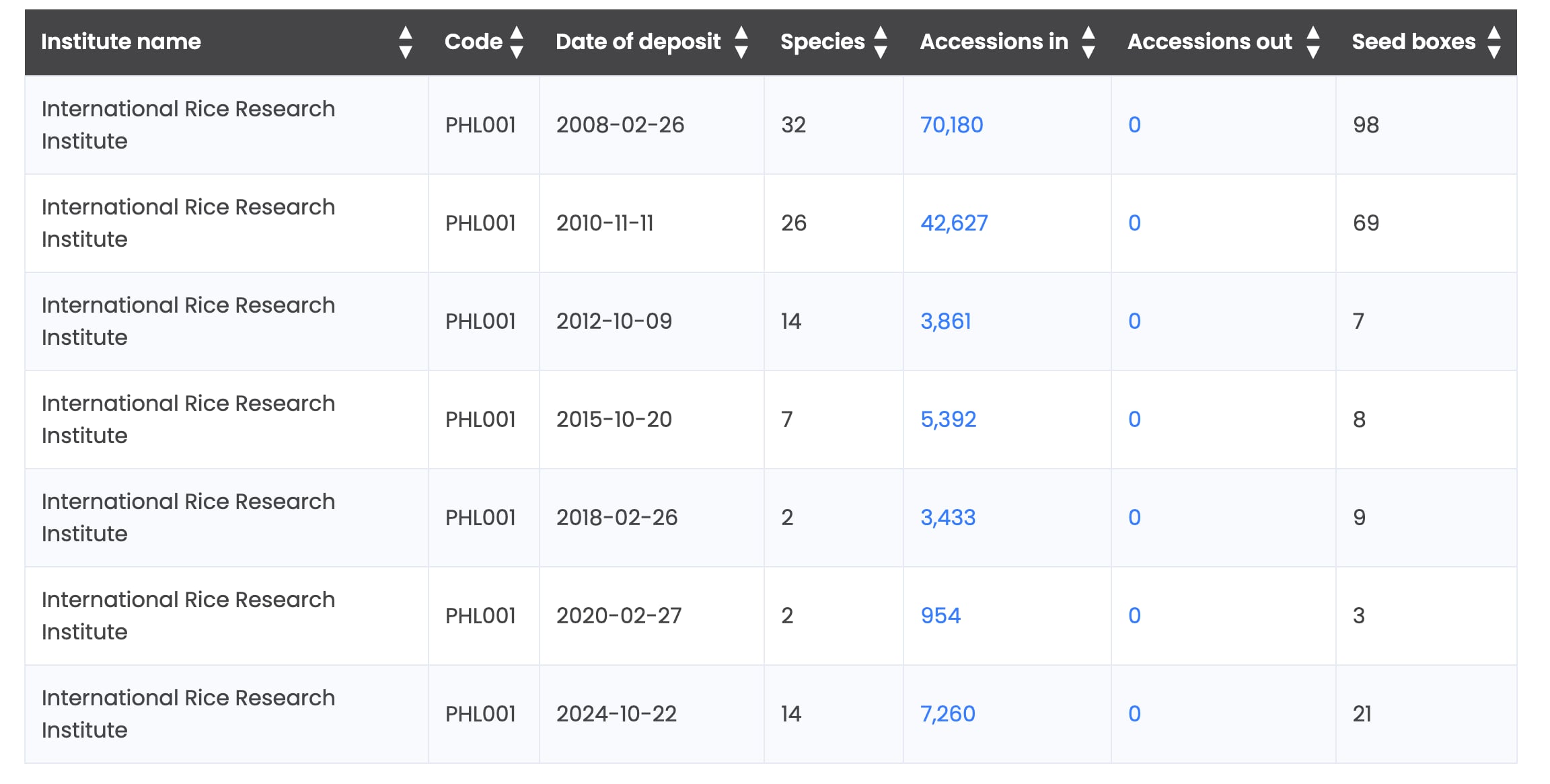

When the SGSV vault was opened in 2008, IRRI deposited more than 70,000 accessions, the first to be registered in the Vault. Since then, IRRI has made six more deposits, for a total of 133,707 accessions, almost the entire collection.

Given the amount of publicity that the SGSV has received, one could be forgiven for not knowing that there are many more genebanks around the world.

Inevitably there has been some misguided (as far as I’m concerned) criticism of the SGSV that I attempted to rebut in the next post.

The IRRI genebank became the first genebank of the CGIAR system to be identified by the Crop Trust for in-perpetuity funding that will ensure the availability of the conserved germplasm decades into the future.

The fact that IRRI was able to deposit so many accessions in the SGSV and receive in-perpetuity funding is due—in no small part—to the many changes we made to the management of the genebank and its collection during the 1990s. And which pre-emptively prepared it for the changes that all the CGIAR genebanks would eventually have to make.

But I’m getting ahead of myself just a little.

Although I had been involved with the conservation and use of plant genetic resources since 1970 (when I arrived at the University of Birmingham to attend the one-year MSc course on genetic conservation), I’d never worked on rice nor managed a genebank when I joined IRRI in 1991. All my experience to date had been with potatoes in South and Central America, and several grain legumes while teaching at Birmingham during the 1980s.

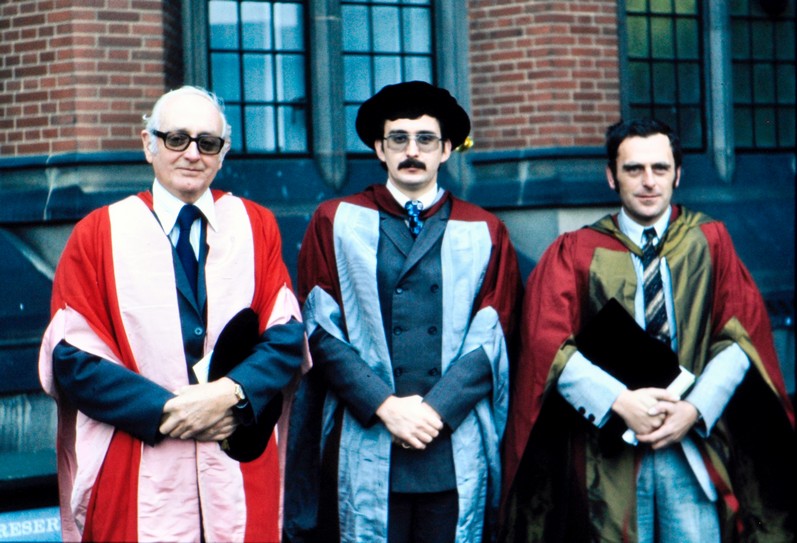

1991 was a fortuitous time to join IRRI. I was recruited by Director General Klaus Lampe (right), who had been appointed by the institute’s Board of Trustees in 1998 to revive the institute’s fortunes and refurbish its ageing infrastructure.

1991 was a fortuitous time to join IRRI. I was recruited by Director General Klaus Lampe (right), who had been appointed by the institute’s Board of Trustees in 1998 to revive the institute’s fortunes and refurbish its ageing infrastructure.

Lampe was very supportive of the genetic resources program, and it helped that I had a senior position as a department head, so was able to meet with him directly on a regular basis to discuss my plans for the genebank.

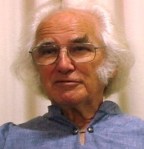

Before 1991 quite a number of staff retired, including the previous and first head of the IRGC, Dr Te-Tzu Chang (known universally simple as ‘TT’). TT and I had very different management styles, and I was determined to involve my genebank staff in the changes that I believed should be made. I spent six months determining how the genebank operations could be significantly enhanced.

As I said, Klaus Lampe was supportive, approving recruitment of junior staff to help with the considerable backlog of seed samples for cleaning and registering in the genebank, as well as including the genebank in the institute’s program of infrastructure refurbishment and equipment upgrades.

These two posts describe many of the changes we made, and include a video about the genebank that I made in 2010 just before I left IRRI.

I was fortunate to inherit a great group of staff, totally dedicated to the genetic conservation cause, and much more knowledgeable about rice than I ever became [3].

I quickly identified Ms Flora ‘Pola’ de Guzman (all Filipinos have a nickname) as a potential genebank manager, and she continued in that role until her retirement a couple of years back. When the in-perpetuity agreement was signed in 2018, Pola was given a special award, recognising her 40 years service to the conservation of rice genetic resources.

Inside the International Rice Genebank Active Collection, with genebank manager Pola de Guzman

I asked Renato ‘Ato’ Reaño to manage all the genebank’s field operations. Ato has also now retired.

One of the key aspects that had to be addressed was data management. As you can imagine, for a collection of 70,000+ accessions that I inherited in 1991, there was a mountain of data about provenance, as well data on morphological characters and response to biotic and abiotic stresses, across the cultivated rices (two different species) and 20+ wild species of Oryza. Essentially there were three databases that couldn’t effectively talk to each other. Big changes had to be made, which I described in this post.

It took almost two years, but when completed we had developed the International Rice Genebank Collection Information System (IRGCIS) to manage all the operations of the genebank. It has now been superseded by an international system based on the US-developed germplasm information network, GRIN.

That information situation also reminds of another information ‘bee in my bonnet’, which I wrote about here.

In my interviews at IRRI in January 1991, I stressed the need for the genebank to carry out research, something that had not been contemplated when the GRC position was advertised the previous year. In fact, I made it a condition of accepting a job offer that the genebank should conduct germplasm-relevant research, such as studies of seed survival, rice taxonomy, and the management of the collection.

I had concerns that we had insufficient information about the longevity of seeds in storage, or how the environment at Los Baños affected the quality of rice seeds grown there. We developed new seed production protocols, and post-harvest management in terms of seed drying. We installed a bespoke seed drying room with a capacity of over 1 tonne of seeds. In the 2000s (after I had moved from GRC to a senior management position at IRRI), seed physiologist Fiona Hay was recruited who improved on the seed handling protocols that we developed and which had already shown to be effective in increasing seed quality for long-term conservation.

Early in the decade, and with funding from the British government, we set up a collaborative project with my former colleagues at the University of Birmingham as well as at the John Innes Centre to study how molecular markers could be used to study the diversity in the rice collection and its management.

In 1994, we received a large grant (>USD 2.3 million) from the Swiss government:

- to collect rice varieties and wild species throughout Asia, Africa, and parts of South America (essentially to try and complete the collecting of germplasm that had been little explored);

- to conduct research about on-farm management of rice genetic resources; and

- to train personnel from national germplasm programs in collecting, conservation techniques, and data management.

During the 1990s, IRRI had a special rice project with the Government of Laos, and a staff member based in Vientiane. Since little rice germplasm had been collected in that country, we recruited Dr Seepana Appa Rao to collect rice varieties there.

Appa Rao (right) and his Lao counterpart, Dr Chay Bounphanousay (left) sampling a rice variety from a Lao farmer.

Over a five year period he and his Lao colleagues collected more than 13,000 samples, now safely conserved in the International Rice Genebank. We also built a small genebank near Vientiane to house the germplasm locally.

My colleagues and I were quite productive in terms of research and publications. This post lists all the publications on which I was author/co-author, and there are links therein to PDF copies of many of them.

Every year, IRRI receives thousands of visitors, and when I first arrived at IRRI, it seemed as if anyone and everyone who wanted to visit the genebank was allowed to do so. On more than one occasion—until I put a stop to it—I’d find our colleagues from Visitor Services taking a large party of visitors, hordes of schoolchildren even, into the cold stores. With such large numbers it was not possible to keep all the doors closed, disrupting the carefully controlled temperature and humidity environment in the genebank and its laboratories.

I had to limit the number of visitors inside the genebank significantly, and ask my staff to take some of the load of attending to visitors. Nevertheless, I do understand the need to explain the importance of genetic resources and the role of the genebank to visitors, and build a constituency who can support the genebank and what it aims to achieve.

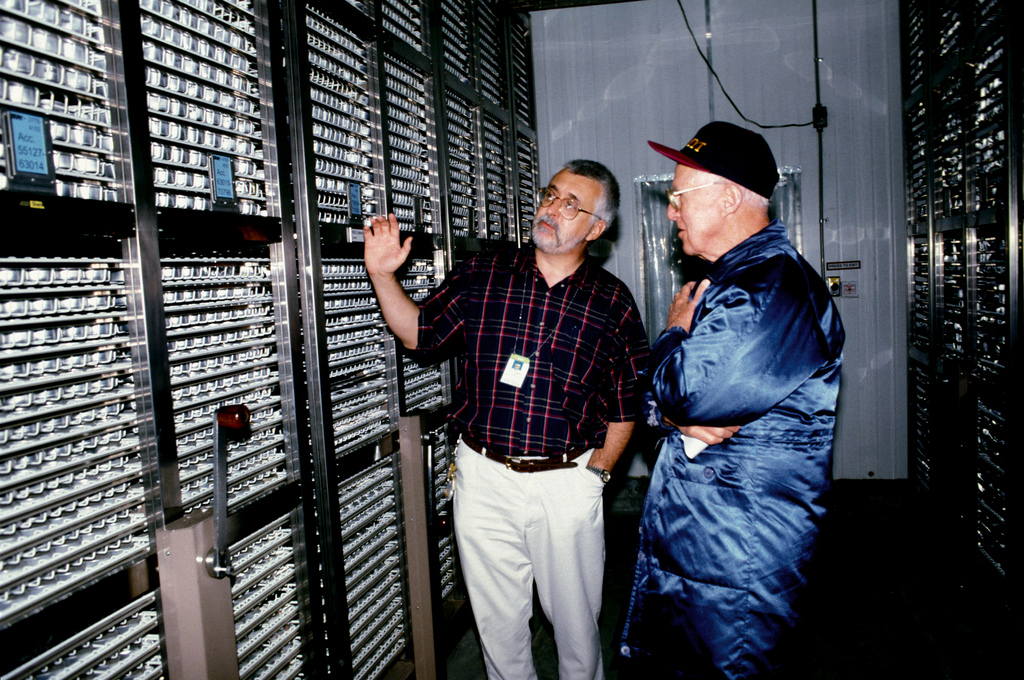

But it was a joy to meet with visitors such as wheat breeder, ‘Father of the Green Revolution’, and 1970 Nobel Peace Laureate, Dr Norman Borlaug.

With Dr Norman Borlaug in the IRG Active Collection in the early 1990s, before we transferred the germplasm to aluminum pouches.

Finally, let me say something about IRRI’s genetic conservation role in the context of the CGIAR.

In the early 1990s, the heads of the CGIAR genebanks would meet each year as the Inter-Center Working Group on Genetic Resources (ICWG-GR). I attended my first meeting in January 1993 in Addis Ababa at the International Livestock Centre for Africa (ILCA, now part of the International Livestock Research Institute or ILRI). I was elected chair for three years, and during my tenure the System-wide Genetic Resources Program (SGRP) was launched with the ICWG-GR as its steering committee.

Earlier I mentioned the CBD. There’s no doubt that during the 1990s the whole realm of genetic resources became highly politicized, with the CGIAR centers contributing to CBD discussions as they related to agricultural biodiversity, and through the FAO Commission on Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture.

Earlier I mentioned the CBD. There’s no doubt that during the 1990s the whole realm of genetic resources became highly politicized, with the CGIAR centers contributing to CBD discussions as they related to agricultural biodiversity, and through the FAO Commission on Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture.

The organization of the genebanks in the CGIAR has undergone several iterations since I moved away from this area in May 2001 (when I joined IRRI’s senior management team as Director for Program Planning and Communications). My successor Dr Ruaraidh Sackville Hamilton enthusiastically took on the role of representing the institute in the discussions on the formulation and implementation of the International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture (ITPGRFA). The Treaty aims to guarantee food security through the conservation, exchange, and sustainable use of the world’s plant genetic resources for food and agriculture. It also focuses on fair and equitable benefit sharing and recognition of farmers’ rights.

In 2016-17, I led a review of the Genebanks CRP (CGIAR Research Program). Since then, the Genebanks CRP evolved into the Genebank Platform, and is now the CGIAR Initiative on Genebanks.

What I can say is that all the CGIAR genebanks have raised their game with respect to the crops they conserve. Working with the Crop Trust, standards have increased, and genebanks held to account more rigorously in terms of how they are being managed. Nevertheless, I think that we can say that the CGIAR continues to play one of the major roles in genetic resources conservation worldwide.

[1] GRC comprised two units: the genebank (my day-to-day responsibility), and the International Network for the Genetic Evaluation of Rice or INGER, which was managed by one of my colleagues.

[2] It seems like only yesterday that I was organizing the institute’s Golden Jubilee in 2010, after which I retired and returned to the UK.

[3] Three key staff, Ms Eves Loresto, Tom Clemeno, and Ms. Amita ‘Amy’ Juliano sadly passed away, as have several other junior staff.

For many years, Steph and I toyed with becoming members of the

For many years, Steph and I toyed with becoming members of the  We received gift membership of

We received gift membership of  The National Trust was the vision of its

The National Trust was the vision of its

I enjoyed my

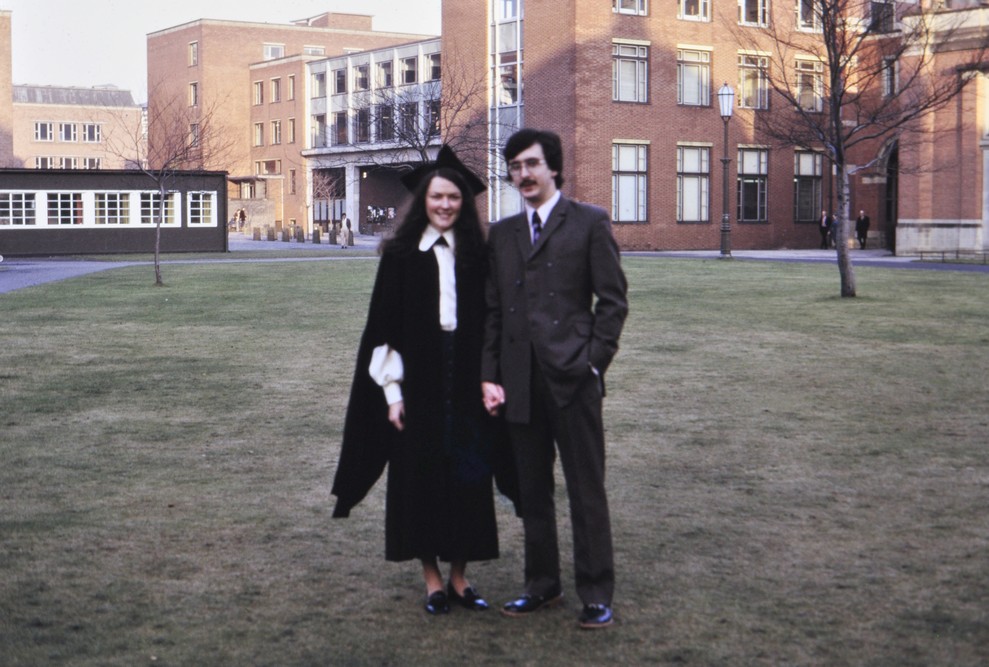

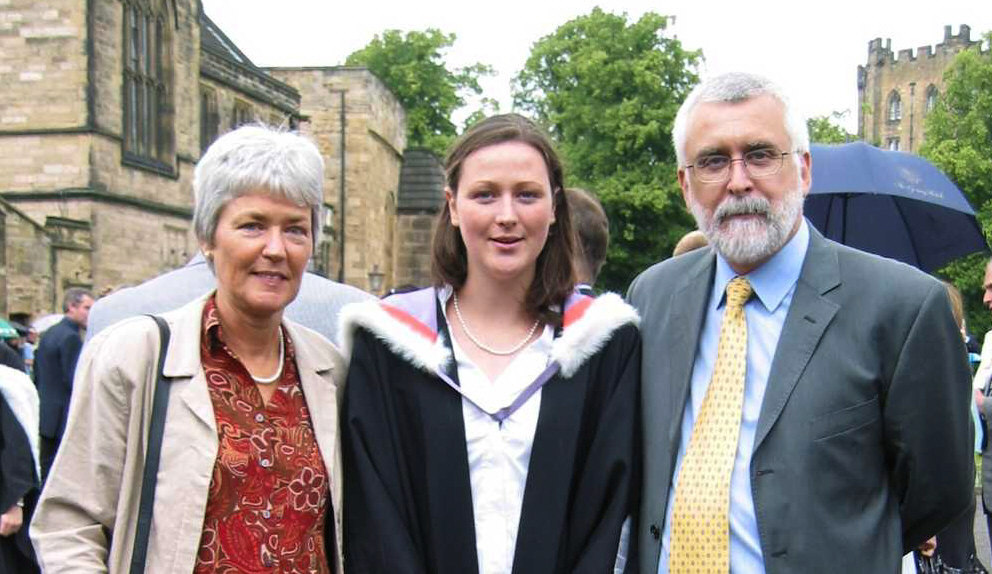

I enjoyed my  A third cohort of students arrived in Birmingham in September 1971, among them Stephanie Tribble from Southend-on-Sea who had just graduated from the

A third cohort of students arrived in Birmingham in September 1971, among them Stephanie Tribble from Southend-on-Sea who had just graduated from the

We upended their world when I took the position at IRRI and they moved to the Philippines with Steph just after Christmas 1991. Even more challenging was their enrolment in the

We upended their world when I took the position at IRRI and they moved to the Philippines with Steph just after Christmas 1991. Even more challenging was their enrolment in the  could transfer to

could transfer to

After a gap year, Philippa began her studies in Psychology at

After a gap year, Philippa began her studies in Psychology at

She spent six months looking for a job, finally landing a research assistantship in the

She spent six months looking for a job, finally landing a research assistantship in the

attention as I was reading a book at the time. High brow Muzak.

attention as I was reading a book at the time. High brow Muzak. I was totally unaware of this interesting back story. Nevertheless, it is a beautiful and much appreciated piece of music, that gained position 170/300 in the Classic FM Hall of Fame 2024. Enjoy this interpretation.

I was totally unaware of this interesting back story. Nevertheless, it is a beautiful and much appreciated piece of music, that gained position 170/300 in the Classic FM Hall of Fame 2024. Enjoy this interpretation.