years ago today (Friday 17 December 1971) I received my MSc degree in Conservation and Utilization of Plant Genetic Resources from the University of Birmingham. Half a century!

years ago today (Friday 17 December 1971) I received my MSc degree in Conservation and Utilization of Plant Genetic Resources from the University of Birmingham. Half a century!

With my dissertation supervisor Dr (later Professor) Trevor Williams, who became the first Director General of the International Board for Plant Genetic Resources (now Bioversity International).

I hadn’t planned to be at the graduation (known as a congregation in UK universities). Why? I had expected to be in Peru for almost three months already. I was set to join the International Potato Center (CIP) (which has just celebrated its 50th anniversary) as an Associate Taxonomist after graduation, but didn’t actually get fly out to Lima until January 1973. Funding for my position from the British government took longer to finalize than had been envisaged. In the meantime, I’d registered for a PhD on the evolution of Andean potato varieties under Professor Jack Hawkes, a world-renowned potato and genetic resources expert.

So let’s see how everything started and progressed.

1970s – potatoes

Having graduated from the University of Southampton in July 1970 (with a BSc degree in Environmental Botany and Geography), I joined the Department of Botany at Birmingham (where Jack Hawkes was head of department) in September that year to begin the one year MSc course, the start of a 39 year career in the UK and three other countries: Peru, Costa Rica, and the Philippines. I took early retirement in 2010 (aged 61) and returned to the UK.

Back in December 1971 I was just relieved to have completed the demanding MSc course. I reckon we studied as hard during that one year as during a three year undergraduate science degree. Looking back on the graduation day itself, I had no inkling that 10 years later I would be back in Birmingham contributing to that very same course as Lecturer in Plant Biology. Anyway, I’m getting ahead of myself.

Arriving in Lima on 4 January 1973, I lived by myself until July when my fiancée Steph flew out to Peru, and join CIP as an Associate Geneticist working with the center’s germplasm collection of Andean potato varieties. She had resigned from a similar position at the Scottish Plant Breeding Station near Edinburgh where she helped conserve the Commonwealth Potato Collection.

Later that year, on 13 October, Steph and I were married in Miraflores, the coastal suburb of Lima where we rented an apartment.

At Pollería La Granja Azul restaurant, east of Lima, after we were married in Miraflores.

My own work in Peru took me all over the Andes collecting potato varieties for the CIP genebank, and conducting field work towards my PhD.

Collecting potato tubers from a farmer in the northern Department of Cajamarca in May 1974.

In May 1975, we returned to Birmingham for just six months so that I could complete the university residency requirements for my PhD, and to write and successfully defend my dissertation. The degree was conferred on 12 December.

Returning to Lima just in time for the New Year celebrations, we spent another three months there before being posted to Turrialba, Costa Rica in Central America at the beginning of April 1976, where we resided until November 1980. The original focus of my research was adaptation of potatoes to hot, humid conditions. But I soon spent much of my time studying the damage done by bacterial wilt, caused by the pathogen Ralstonia solancearum (formerly Pseudomonas solanacearum).

Checking the level of disease in a bacterial wilt trial of potatoes in Turrialba, July 1977.

Each year I made several trips throughout Central America, to Mexico, and various countries in the Caribbean, helping to set up a collaborative research project, PRECODEPA, which outlasted my stay in the region by more than 20 years. One important component of the project was rapid multiplication systems for potato seed production for which my Lima-based colleague, Jim Bryan, joined me in Costa Rica for one year in 1979.

My two research assistants (in blue lab-coats), Moises Pereira (L) and Jorge Aguilar (R) demonstrating leaf cuttings to a group of potato agronomists from Guatemala, Panama, the Dominican Republic, and Costa Rica, while my CIP colleague and senior seed production specialist, Jim Bryan, looks on.

There’s one very important thing I want to mention here. At the start of my career with CIP, as a young germplasm scientist, and moving to regional work in Costa Rica, I count myself extremely fortunate I was mentored through those formative years in international agricultural research by two remarkable individuals.

Roger Rowe and Ken Brown

Dr Roger Rowe joined CIP in July 1973 as head of the Breeding and Genetics Department. He was my boss (and Steph’s), and he also co-supervised my PhD research. I’ve kept in touch with Roger ever since. I’ve always appreciated the advice he gave me. And even after I moved to IRRI in 1991, our paths crossed professionally. When Roger expressed an opinion it was wise to listen.

Dr Ken Brown joined CIP in January 1976 and became Director of the Regional Research Program. He was my boss during the years I worked in Central America. He was very supportive of my work on bacterial wilt and the development of PRECODEPA. Never micro-managing his staff, I learned a lot from Ken about people and program management that stood me in good stead in the years to come.

1980s – academia

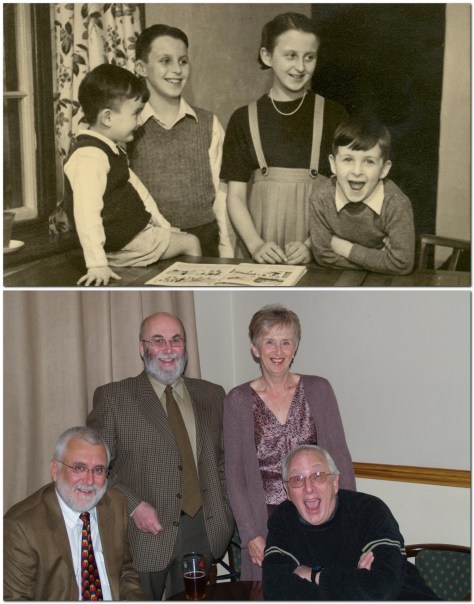

By the middle of 1980 I was beginning to get itchy feet. I couldn’t see myself staying in Costa Rica much longer, even though Steph and I enjoyed our life there. It’s such a beautiful country. Our elder daughter Hannah was born there in April 1978.

To grow professionally I needed other challenges, so asked my Director General in Lima, Richard Sawyer, about the opportunity of moving to another region, with a similar program management and research role. Sawyer decided to send me to Southeast Asia, in the Philippines, to take over from my Australian colleague Lin Harmsworth after his retirement in 1982.

However, I never got to the Philippines. Well, not for another decade. In the meantime I had been encouraged to apply for a lectureship at the University of Birmingham. In early 1981 I successfully interviewed and took up the position there in April.

However, I never got to the Philippines. Well, not for another decade. In the meantime I had been encouraged to apply for a lectureship at the University of Birmingham. In early 1981 I successfully interviewed and took up the position there in April.

Thus my international potato decade came to an end, as did any thoughts of continuing in international agricultural research. Or so it seemed at the time.

For three months I lodged with one of my colleagues, John Dodds, who had an apartment close to the university’s Edgbaston campus while we hunted for a house to buy. Steph and Hannah stayed with her parents in Southend on Sea (east of London), and I would travel there each weekend.

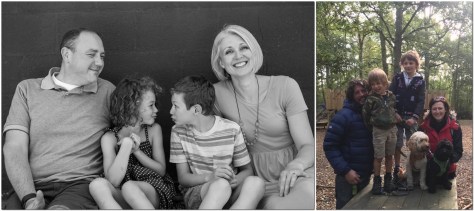

It took only a couple of weeks to find a house that suited us, in the market town of Bromsgrove, Worcestershire, about 13 miles south of the university. We moved in during the first week of July, and kept the house for almost 40 years until we moved to Newcastle upon Tyne in the northeast of England almost 15 months ago. However we didn’t live there continually throughout that period as will become apparent below.

Our younger daughter Philippa was born in Bromsgrove in May 1982. How does the saying go? New house, new baby!

With Brian when we attended a Mediterranean genetic resources conference in Izmir, Turkey in April 1972. Long hair was the style back in the day.

I threw myself into academic life with enthusiasm. Most of my teaching was for the MSc genetic conservation students, some to second year undergraduates, and a shared ten-week genetic conservation module for third year undergraduates with my close friend and colleague of more than 50 years, Brian Ford-Lloyd.

I also supervised several PhD students during my time at Birmingham, and I found that role particularly satisfying. As I did tutoring undergraduate students; I tutored five or six each year over the decade. Several tutees went on to complete a PhD, two of whom became professors and were recently elected Fellows of the Royal Society.

One milestone for Brian and me was the publication, in 1986, of our introductory text on plant genetic resources, one of the first books in this field, and which sold out within 18 months. It’s still available as a digital print on demand publication from Cambridge University Press.

One milestone for Brian and me was the publication, in 1986, of our introductory text on plant genetic resources, one of the first books in this field, and which sold out within 18 months. It’s still available as a digital print on demand publication from Cambridge University Press.

This was followed in 1990 by a co-edited book (with geography professor Martin Parry) about genetic resources and climate change, a pioneering text at least a decade before climate change became widely accepted. We followed up with an updated publication in 2014.

The cover of our 1990 book (L), and at the launch of the 2014 book, with Brian Ford-Lloyd in December 2013

My research interests in potatoes continued with a major project on true potato seed collaboratively with the Plant Breeding Institute in Cambridge (until Margaret Thatcher’s government sold it to the private sector) and CIP. My graduate students worked on a number of species including potatoes and legumes such as Lathyrus.

However, I fully appreciated my research limitations, and enjoyed much more the teaching and administrative work I was asked to take on. All in all, the 1980s in academia were quite satisfying. Until they weren’t. By about 1989, when Margaret Thatcher had the higher education sector firmly in her sights, I became less enthusiastic about university life.

And, in September 1990, an announcement landed in my mailbox for a senior position at the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) in the Philippines. I applied to become head of the newly-created Genetic Resources Center (GRC, incorporating the International Rice Genebank), and joined IRRI on 1 July 1991. The rest is history.

I’ve often been asked how hard it was to resign from a tenured position at the university. Not very hard at all. Even though I was about to be promoted to Senior Lecturer. But the lure of resuming my career in the CGIAR was too great to resist.

I’ve often been asked how hard it was to resign from a tenured position at the university. Not very hard at all. Even though I was about to be promoted to Senior Lecturer. But the lure of resuming my career in the CGIAR was too great to resist.

1990s – rice genetic resources

I never expected to remain at IRRI much beyond 10 years, never mind the 19 that we actually spent there.

Klaus Lampe

I spent the first six months of my assignment at IRRI on my own. Steph and the girls did not join me until just before the New Year. We’d agreed that it would be best if I spent those first months finding my feet at IRRI. I knew that IRRI’s Director General, Dr Klaus Lampe, expected me to reorganize the genebank. And I also had the challenge of bringing together in GRC two independent units: the International Rice Germplasm Center (the genebank) and the International Network for the Genetic Evaluation of Rice (INGER). No mean feat as the INGER staff were reluctant, to say the least, to ever consider themselves part of GRC. But that’s another story.

Elsewhere in this blog I’ve written about the challenges of managing the genebank, of sorting out the data clutter I’d inherited, investigating how to improve the quality of seeds stored in the genebank, collaborating with my former colleagues at Birmingham to improve the management and use of the rice collection by using molecular markers to study genetic diversity, as well as running a five year project (funded by the Swiss government) to safeguard rice biodiversity.

I was also heavily involved with the CGIAR’s Inter-Center Working Group on Genetic Resources (ICWG-GR), attending my first meeting in January 1993 in Addis Ababa, when I was elected Chair for the next three years.

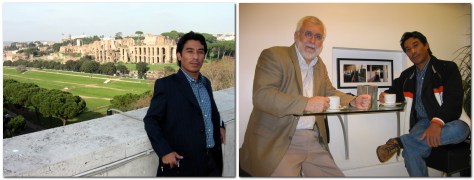

In that role I oversaw the development of the System-wide Genetic Resources Program (SGRP), and visited Rome several times a year to the headquarters of the International Plant Genetic Resources Institute (IPGRI, now Bioversity International) which hosted the SGRP Secretariat.

In that role I oversaw the development of the System-wide Genetic Resources Program (SGRP), and visited Rome several times a year to the headquarters of the International Plant Genetic Resources Institute (IPGRI, now Bioversity International) which hosted the SGRP Secretariat.

But in early 2001 I was offered an opportunity (which I initially turned down) to advance my career in a totally different direction. I was asked to join IRRI’s senior management team in the newly-created post of Director for Program Planning and Coordination.

The 2000s – management

It must have been mid-January 2001. Sylvia, the Director General’s secretary, asked me to attend a meeting in the DG’s office just after lunch. I had no idea what to expect, and was quite surprised to find not only the DG, Dr Ron Cantrell, there but also his two deputies, Dr Willy Padolina (DDG-International Programs) and Dr Ren Wang, DDG-Research.

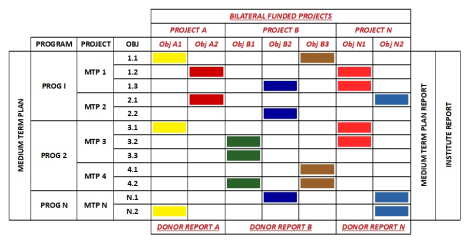

To cut a long story short, Cantrell asked me to leave GRC and move into a new position, as one of the institute’s directors, and take over the management of resource mobilization and donor relations, among other responsibilities (after about one year I was given line management responsibility for the Development Office [DO], the Library and Documentation Services [LDS], Communication and Publications Services [CPS], and the Information Technology Services [ITS]).

With my unit heads, L-R: me, Gene Hettel (CPS), Mila Ramos (LDS), Marco van den Berg (ITS), Duncan Macintosh (DO), and Corinta Guerta (DPPC).

In DPPC, as it became known, we established all the protocols and tracking systems for the many research projects and donor communications essential for the efficient running of the institute. I recruited a small team of five individuals, with Corinta Guerta becoming my second in command, who herself took over the running of the unit after my retirement in 2010 and became a director. Not bad for someone who’d joined IRRI three decades earlier as a research assistant in soil chemistry. We reversed the institute’s rather dire reputation for research management and reporting (at least in the donors’ eyes), helping to increase IRRI’s budget significantly over the nine years I was in charge.

With, L-R, Yeyet, Corinta, Zeny, Vel, (me), and Eric.

I’m not going to elaborate further as the details can be found in that earlier blog post. What I can say is that the time I spent as Director for Program Planning and Communications (the Coordination was dropped once I’d taken on the broader management responsibilities) were among the most satisfying professionally, and a high note on which to retire. 30 April 2010 was my last day in the office.

Since then, and once settled into happy retirement, I’ve kept myself busy by organizing two international rice research conferences (in Vietnam in 2010 and Thailand in 2014), co-edited the climate change book I referred to earlier, and been the lead on a major review of the CGIAR’s Genebank Program (in 2017). Once that review was completed, I decided I wouldn’t take on any more consultancy commitments, and I also stepped down from the editorial board of the Springer scientific journal Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution.

As I said from the outset of this post, it’s hard to imagine that this all kicked off half a century ago. I can say, without hesitation and unequivocally, that I couldn’t have hoped for a more rewarding career. Not only in the things we did and the many achievements, but the friendships forged with many people I met and worked with in more than 60 countries. It was a blast!

I came across a tweet a few days ago from the

I came across a tweet a few days ago from the  CGIAR? As Bill Gates

CGIAR? As Bill Gates

largest and most

largest and most

Forty-seven years ago, I was getting ready to fly to Peru, to join the

Forty-seven years ago, I was getting ready to fly to Peru, to join the  In January 1981, I was invited to interview for a

In January 1981, I was invited to interview for a

One thing I did know, however: I wanted my secretary from GRC, Zeny Federico, to join me in DPPC, and she readily accepted my invitation.

One thing I did know, however: I wanted my secretary from GRC, Zeny Federico, to join me in DPPC, and she readily accepted my invitation.

Starting a career in international agricultural research

Starting a career in international agricultural research

The day after our meetings, we caught the Thalys (the Belgian TGV) to Cologne, and then a regional service for the short hop to Bonn. We had just one day of meetings in Bonn, with the German aid ministry (BMZ), and then spent an excellent day touring the vineyards of the Ahr Valley just south of Bonn. Our main contact was my old friend Marlene Diekmann who I’d known for many years before she joined the BMZ when she was a plant pathologist at the International Plant Genetic Resources Institute (IPGRI, now Bioversity International) in Rome.

The day after our meetings, we caught the Thalys (the Belgian TGV) to Cologne, and then a regional service for the short hop to Bonn. We had just one day of meetings in Bonn, with the German aid ministry (BMZ), and then spent an excellent day touring the vineyards of the Ahr Valley just south of Bonn. Our main contact was my old friend Marlene Diekmann who I’d known for many years before she joined the BMZ when she was a plant pathologist at the International Plant Genetic Resources Institute (IPGRI, now Bioversity International) in Rome.

My decision to leave a tenured position at the University of Birmingham in June 1991 was not made lightly. I was about to be promoted to Senior Lecturer, and I’d found my ‘home’ in the Plant Genetics Research Group following the reorganization of the School of Biological Sciences a couple of years earlier.

My decision to leave a tenured position at the University of Birmingham in June 1991 was not made lightly. I was about to be promoted to Senior Lecturer, and I’d found my ‘home’ in the Plant Genetics Research Group following the reorganization of the School of Biological Sciences a couple of years earlier. I felt as though I was treading water, trying to keep my head above the surface. I had a significant teaching load, research was ticking along, PhD and MSc students were moving through the system, but still the university demanded more. So when an announcement of a new position as Head of the Genetic Resources Center (GRC) at the

I felt as though I was treading water, trying to keep my head above the surface. I had a significant teaching load, research was ticking along, PhD and MSc students were moving through the system, but still the university demanded more. So when an announcement of a new position as Head of the Genetic Resources Center (GRC) at the

Once in post at IRRI, I asked lots of questions. For at least six months until the end of 1991, I made no decisions about changes in direction for the genebank until I better understood how it operated and what constraints it faced. I also had to size up the caliber of staff, and develop a plan for further staff recruitment. I did persuade IRRI management to increase resource allocation to the genebank, and we were then able to hire technical staff to support many time critical areas.

Once in post at IRRI, I asked lots of questions. For at least six months until the end of 1991, I made no decisions about changes in direction for the genebank until I better understood how it operated and what constraints it faced. I also had to size up the caliber of staff, and develop a plan for further staff recruitment. I did persuade IRRI management to increase resource allocation to the genebank, and we were then able to hire technical staff to support many time critical areas. Dr Kameswara Rao (from IRRI’s sister center ICRISAT, based in Hyderabad, India) joined GRC to work on the relationship between seed quality and seed growing environment. He had received his PhD from the University of Reading, and this research had started as a collaboration with Professor Richard Ellis there. Rao’s work led to some significant changes to our seed production protocols.

Dr Kameswara Rao (from IRRI’s sister center ICRISAT, based in Hyderabad, India) joined GRC to work on the relationship between seed quality and seed growing environment. He had received his PhD from the University of Reading, and this research had started as a collaboration with Professor Richard Ellis there. Rao’s work led to some significant changes to our seed production protocols. In 1994, I developed a

In 1994, I developed a

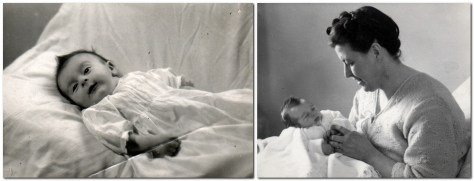

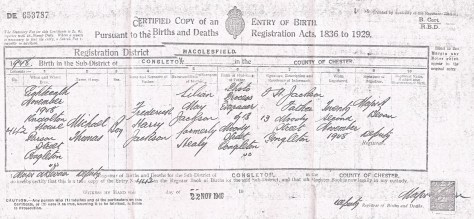

18 November 1948. Today is my 70th birthday. Septuagenarian. The Biblical three score and ten (Psalm 90:10)!

18 November 1948. Today is my 70th birthday. Septuagenarian. The Biblical three score and ten (Psalm 90:10)!

I was also a cub scout, as was Ed.

I was also a cub scout, as was Ed.

I passed my 11 Plus exam to attend a Roman Catholic grammar school,

I passed my 11 Plus exam to attend a Roman Catholic grammar school,

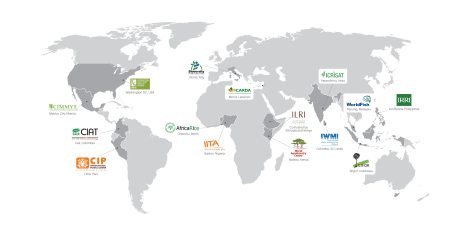

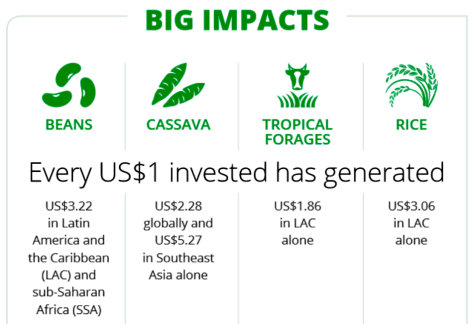

All four centers are members of the

All four centers are members of the

In 1969, World Bank President Robert McNamara (who had been US Secretary of Defense under Presidents Kennedy and Johnson) wrote to the heads of the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) in Rome and the United Nations Development Fund (UNDP) in New York saying: I am writing to propose that the FAO, the UNDP and the World Bank jointly undertake to organize a long-term program of support for regional agricultural research institutes. I have in mind support not only for some of the existing institutes, including the four now being supported by the Ford and Rockefeller Foundations [IRRI, CIMMYT, IITA, and CIAT], but also, as occasion permits, for a number of new ones.

In 1969, World Bank President Robert McNamara (who had been US Secretary of Defense under Presidents Kennedy and Johnson) wrote to the heads of the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) in Rome and the United Nations Development Fund (UNDP) in New York saying: I am writing to propose that the FAO, the UNDP and the World Bank jointly undertake to organize a long-term program of support for regional agricultural research institutes. I have in mind support not only for some of the existing institutes, including the four now being supported by the Ford and Rockefeller Foundations [IRRI, CIMMYT, IITA, and CIAT], but also, as occasion permits, for a number of new ones.

And that’s how I got into research management in 2001, when IRRI Director General Ron Cantrell invited me to join the senior management team as

And that’s how I got into research management in 2001, when IRRI Director General Ron Cantrell invited me to join the senior management team as

Soccie Almazan became the curator of the wild rices that had to be grown in a quarantine screenhouse some distance from the main research facilities, on the far side of the experiment station. But the one big change that we made was to incorporate all the germplasm types, cultivated or wild, into a single genebank collection, rather than the three collections. Soccie brought about some major changes in how the wild species were handled, and with an expansion of the screenhouses in the early 1990s (as part of the overall refurbishment of institute infrastructure) the genebank at last had the space to adequately grow (in pots) all this valuable germplasm that required special attention. See the video from 4:30. Soccie retired from IRRI in the last couple of years.

Soccie Almazan became the curator of the wild rices that had to be grown in a quarantine screenhouse some distance from the main research facilities, on the far side of the experiment station. But the one big change that we made was to incorporate all the germplasm types, cultivated or wild, into a single genebank collection, rather than the three collections. Soccie brought about some major changes in how the wild species were handled, and with an expansion of the screenhouses in the early 1990s (as part of the overall refurbishment of institute infrastructure) the genebank at last had the space to adequately grow (in pots) all this valuable germplasm that required special attention. See the video from 4:30. Soccie retired from IRRI in the last couple of years.

Well, the short answer is that at the end of October, the last member of my original DPPC team, Zeny Federico, will retire. Others have retired already, moved on to bigger and better things, or moved to other positions in the institute. It’s the end of an era! DPPC no longer exists. Shortly after I retired it changed its name to DRPC—Donor Relations and Project Coordination, and is to become the IRRI Portfolio Management Office (IPMO).

Well, the short answer is that at the end of October, the last member of my original DPPC team, Zeny Federico, will retire. Others have retired already, moved on to bigger and better things, or moved to other positions in the institute. It’s the end of an era! DPPC no longer exists. Shortly after I retired it changed its name to DRPC—Donor Relations and Project Coordination, and is to become the IRRI Portfolio Management Office (IPMO).

And that person was Corinta Guerta, a soil chemist and Senior Associate Scientist working on the adaptation of rice varieties to problem soils. A soil chemist, you might ask? When discussing my new role with Ron Cantrell in early 2001, I’d already mentioned Corinta’s name as someone I would like to try and recruit. What in her experience would qualify Corints (as we know her) to take up a role in donor relations and project management?

And that person was Corinta Guerta, a soil chemist and Senior Associate Scientist working on the adaptation of rice varieties to problem soils. A soil chemist, you might ask? When discussing my new role with Ron Cantrell in early 2001, I’d already mentioned Corinta’s name as someone I would like to try and recruit. What in her experience would qualify Corints (as we know her) to take up a role in donor relations and project management?

When Corints and I interviewed Eric, he quickly understood the essential elements of what we wanted to do, and had potential solutions to hand. Potential became reality! I don’t remember exactly when Eric joined us in DPPC. It must have been around September or October 2001, but within six months we had a functional online grants management system that already moved significantly ahead of where the CIAT system has languished for some time. Our system went from strength to strength and was much admired, envied even, among professionals at the other centers who had similar remits to DPPC.

When Corints and I interviewed Eric, he quickly understood the essential elements of what we wanted to do, and had potential solutions to hand. Potential became reality! I don’t remember exactly when Eric joined us in DPPC. It must have been around September or October 2001, but within six months we had a functional online grants management system that already moved significantly ahead of where the CIAT system has languished for some time. Our system went from strength to strength and was much admired, envied even, among professionals at the other centers who had similar remits to DPPC.

Come October 2015, Yeyet decided to seek pastures new, and joined

Come October 2015, Yeyet decided to seek pastures new, and joined

Nominally the ‘junior’ in DPPC, Vel very quickly became an indispensable member of the team, taking on more responsibilities related to data management. She has a degree in computer science. However, just a month or so back, an opportunity presented itself elsewhere in the institute, and Vel moved to the Seed Health Unit (SHU) as the Material Transfer Agreements Controller. As the SHU is responsible for all imports and exports of rice seeds under the terms of the International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture using Material Transfer Agreements, Vel’s role is important to ensure that the institute is compliant under its agreement with FAO for the exchange of rice germplasm. Vel married Jason a few years back, and they have two delightful daughters.

Nominally the ‘junior’ in DPPC, Vel very quickly became an indispensable member of the team, taking on more responsibilities related to data management. She has a degree in computer science. However, just a month or so back, an opportunity presented itself elsewhere in the institute, and Vel moved to the Seed Health Unit (SHU) as the Material Transfer Agreements Controller. As the SHU is responsible for all imports and exports of rice seeds under the terms of the International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture using Material Transfer Agreements, Vel’s role is important to ensure that the institute is compliant under its agreement with FAO for the exchange of rice germplasm. Vel married Jason a few years back, and they have two delightful daughters. Inspector General at FAO in Rome for six years from February 2010), and whose office was just down the corridor from mine, we decided to develop a bottom-up approach, but needed a safe pair of hands to manage this full-time. So we hired Alma Redillas Dolot as a consultant, and she stayed with DPPC for a couple of years before joining the IAU.

Inspector General at FAO in Rome for six years from February 2010), and whose office was just down the corridor from mine, we decided to develop a bottom-up approach, but needed a safe pair of hands to manage this full-time. So we hired Alma Redillas Dolot as a consultant, and she stayed with DPPC for a couple of years before joining the IAU.

I call it ‘the San Miguel effect’. Whatever is that, I hear you cry? San Miguel is the principal brand of beer brewed in the Philippines (it had cornered 95% of the market by 2008). And as I always told

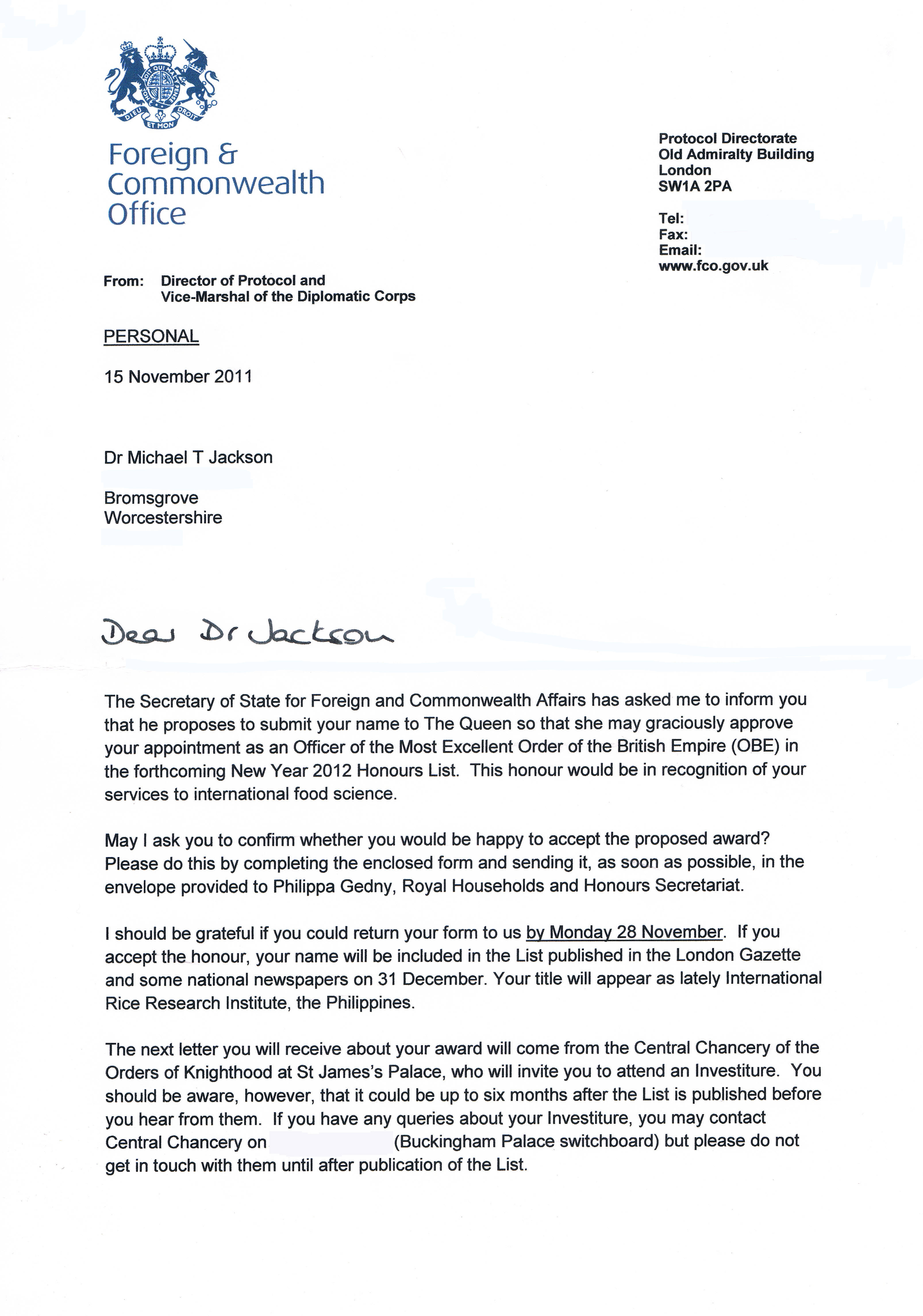

I call it ‘the San Miguel effect’. Whatever is that, I hear you cry? San Miguel is the principal brand of beer brewed in the Philippines (it had cornered 95% of the market by 2008). And as I always told  On a bright, sunny day last November (my birthday, actually) I was outside cleaning the car, when the postman passed by. He handed me several envelopes and my immediate reaction was that this was another load of the usual junk mail. So you can imagine my surprise when I came across one that seemed rather official looking. And I was even more surprised when I read what it had to say – that I had been nominated to become an Officer of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire, or OBE, for services to international food science. Well, I was gob-smacked, quite emotional really. I rushed inside to tell Steph – who was equally stunned, and we set to ponder how on earth this had come about. I did some Google detective work, and was able to find out a little more about the

On a bright, sunny day last November (my birthday, actually) I was outside cleaning the car, when the postman passed by. He handed me several envelopes and my immediate reaction was that this was another load of the usual junk mail. So you can imagine my surprise when I came across one that seemed rather official looking. And I was even more surprised when I read what it had to say – that I had been nominated to become an Officer of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire, or OBE, for services to international food science. Well, I was gob-smacked, quite emotional really. I rushed inside to tell Steph – who was equally stunned, and we set to ponder how on earth this had come about. I did some Google detective work, and was able to find out a little more about the