Education is a wonderful thing, and my family and I have taken advantage of the opportunities a good education opens up.

As I read an email a few days ago from the University of Birmingham, announcing its 125th anniversary celebrations later this year, my mind wandered back to 1975.

That was when the university celebrated the centennial of laying of the foundation stone of the Mason Science College in 1875, itself a successor of Queen’s College, founded in 1825 as a medical college. HM The Queen visited the university in 1975 to celebrate that centennial, seen in this photo with the university Chancellor, Sir Peter Scott (on the right) and the Vice-Chancellor, Dr Robert Hunter (later Baron Hunter of Newington, on the left). I was in the crowd there, somewhere.

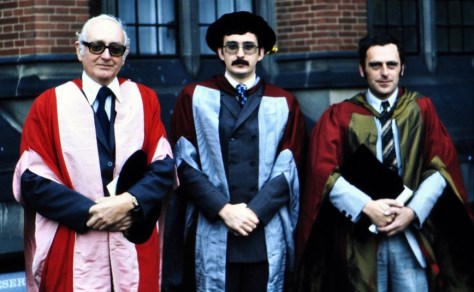

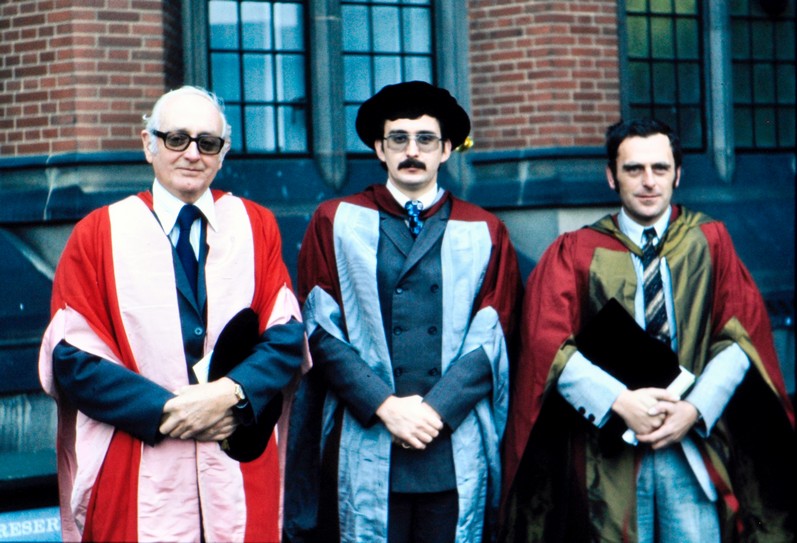

I was back at Birmingham for a few months (from the International Potato Center or CIP in Lima, Peru where I was working as an Associate Taxonomist) to complete the residency requirements for my PhD, and to submit my dissertation. I successfully defended that in late October, and the degree was conferred by Sir Peter Scott at a congregation on 12 December. In the photo below, my PhD supervisor and Mason Professor of Botany, Jack Hawkes is on my right, and Dr Trevor Williams on my left.

But I’m getting a little ahead of myself.

My first experience of Birmingham was in the late Spring of 1967, when I sat the Joint Matriculation Board Advanced or ‘A’ Level biology practical exam in the First Year Lab in the School of Biological Sciences. Many high schools took advantage of that arrangement if they had insufficient facilities in their own premises to hold the exam.

Going into my ‘A’ level exams I had ambitions to attend university. Not that I’d applied to Birmingham. That honour went to the University of Southampton where I had been accepted to study for a BSc degree in environmental botany and geography.

As ‘baby boomers’ my elder brother Edgar and I were the first in our family and among all our cousins to attend university. Once Edgar had persuaded our parents that he wanted to go to university (1964-1967) it was easier for me to follow that same path three years later.

I enjoyed my three years at Southampton. Although I’d registered for a combined degree in environmental botany and geography, my interests shifted significantly towards botany by my third and final year.

I enjoyed my three years at Southampton. Although I’d registered for a combined degree in environmental botany and geography, my interests shifted significantly towards botany by my third and final year.

However, graduating in July 1970 and with just a BSc under my belt, I knew I’d have to pursue graduate studies to achieve my ambition of working overseas. And it was at the beginning of my final year at Southampton that a one year taught MSc course on the Conservation and Utilisation of Plant Genetic Resources was launched at Birmingham, under the leadership of Jack Hawkes. One of the lecturers at Southampton, geneticist Dr Joe Smartt, suggested that I should apply.

Which I duly did, and after an interview at Birmingham was offered a place for the following September, subject to funding being available for a maintenance grant and tuition fees. It was not until the course was about to commence that Professor Hawkes could confirm the financial support. By mid-September I headed to Birmingham, and the beginning of an association with the university that lasted several decades, as both student and member of staff.

I was awarded the MSc degree in December 1971. During that year, Hawkes (a world-renowned potato expert) had arranged for me to join CIP in Lima for just a year (which later extended to more than eight years) to help conserve its important collection of native potato varieties. An opportunity I jumped at. However, funding from the British government was not confirmed until late 1972. Instead of kicking my heels waiting for that funding to be confirmed, and concerned I might find a position elsewhere, Hawkes raised a small grant to allow me to begin a PhD project under his supervision, and that I would continue after arriving in Peru.

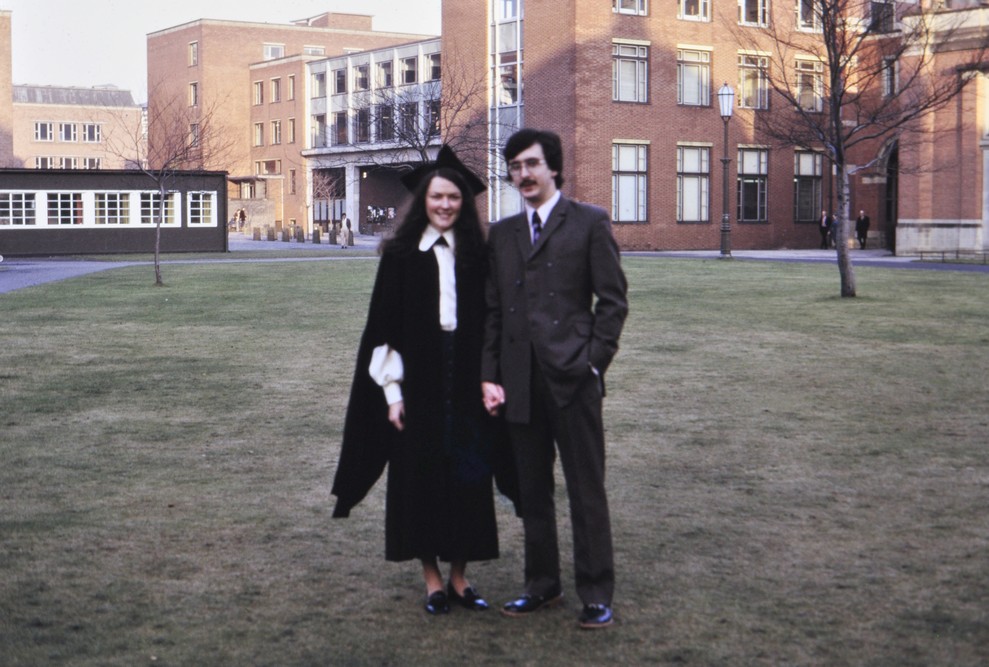

A third cohort of students arrived in Birmingham in September 1971, among them Stephanie Tribble from Southend-on-Sea who had just graduated from the University College of Swansea (now Swansea University) with a degree in botany. By the summer of 1972 Steph and I had become an item.

A third cohort of students arrived in Birmingham in September 1971, among them Stephanie Tribble from Southend-on-Sea who had just graduated from the University College of Swansea (now Swansea University) with a degree in botany. By the summer of 1972 Steph and I had become an item.

In November 1972 she joined the Scottish Plant Breeding Station (SPBS) at Pentlandfield, south of Edinburgh, as assistant curator of the Commonwealth Potato Collection. She returned to Birmingham in December for the MSc degree congregation, just three weeks before I was due to fly out to Peru at the beginning of January 1973.

Well, things have a habit of turning out for the best. Once I was in Peru, I asked Steph to marry me and join me in Lima where I knew there would be a position for her at CIP. Resigning from the SPBS, she arrived in early July and we were married in the local registry office in Lima in October.

So that’s two botanists, three universities (Southampton, Swansea, and Birmingham), and five degrees (2xBSc, 2xMSc, 1xPhD) between us.

After another fruitful five years with CIP based in Costa Rica after I’d completed my PhD (during which our elder daughter Hannah was born), a lectureship opened in the Department of Plant Biology at Birmingham, so I applied. I flew back from Peru for an interview, and having been offered the position, I joined the university on 1 April 1981.

Much of my teaching focused on the genetic resources MSc course that was accepting ever more numbers of students from around the world. I remained at Birmingham for a decade, before deciding that I wasn’t really cut out for academia and, in any case, a more exciting opportunity had presented itself at the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) in the Philippines. I joined IRRI as head of the Genetic Resources Center in July 1991, remaining in that position for almost a decade. In May 2001, I was appointed Director for Program Planning and Communications (DPPC), joining the institute’s senior management team, until my retirement in April 2010.

During the 1990s, I had an excellent research collaboration with my former colleagues in the School of Biological Sciences at Birmingham, and each year when I returned to the UK on home leave, I’d spend time in the university discussing our research as well as delivering several lectures to the MSc students, for which the university appointed me an Honorary Senior Lecturer.

As I mentioned before, Hannah was born in 1978 when we were living in Costa Rica. Once back in the UK her younger sister Philippa was born in 1982 in the small market town of Bromsgrove, about 13 miles south of the University of Birmingham in north Worcestershire.

Both girls thrived in Bromsgrove, enjoyed school, and each had a good circle of friends.

We upended their world when I took the position at IRRI and they moved to the Philippines with Steph just after Christmas 1991. Even more challenging was their enrolment in the International School Manila, which had a US-based curriculum, and eventually an academic stream based on the International Baccalaureate (IB). There’s no doubt that the first year was tough. Not only was it challenging academically, but living 70 km south of Manila, IRRI students were bussed into school each day departing around 04:30 to begin classes at 07:30, and returning by 16:30, or later if there were holdups on the highway, as was often the case.

We upended their world when I took the position at IRRI and they moved to the Philippines with Steph just after Christmas 1991. Even more challenging was their enrolment in the International School Manila, which had a US-based curriculum, and eventually an academic stream based on the International Baccalaureate (IB). There’s no doubt that the first year was tough. Not only was it challenging academically, but living 70 km south of Manila, IRRI students were bussed into school each day departing around 04:30 to begin classes at 07:30, and returning by 16:30, or later if there were holdups on the highway, as was often the case.

Despite the bumpy start, Hannah and Phil rose to the challenge and achieved outstanding scores on the IB in 1995 and 1999 respectively.

From the outset, attending university had been part of our plan for them, and an ambition they readily embraced. Both took a gap year between high school and university. Hannah was drawn towards Psychology, with a minor in Anthropology. And she discovered that this combination was offered at few universities in the UK, opting to attend Swansea University in 1996. And although she was on course to excel academically, half way through her second year she asked if she  could transfer to Macalester College, a liberal arts college in Minnesota, USA.

could transfer to Macalester College, a liberal arts college in Minnesota, USA.

Macalester graduation in May 2000, with Hannah and Michael facing the camera.

Graduating Summa cum laude in May 2000 from Macalester, with a BA in Psychology and a minor in Anthropology, Hannah was then accepted into a graduate ![]() program in the Department of Psychology at the University of Minnesota in the Twin Cities.

program in the Department of Psychology at the University of Minnesota in the Twin Cities.

She was awarded her PhD in Industrial and Organizational Psychology in 2006 with a thesis that assessed the behaviour and ethical misconduct of senior leaders in the workplace.

Hannah (right) with her peers in Industrial & organizational Psychology

That’s one psychologist, another two universities (Macalester and Minnesota), and two more degrees (BA, PhD).

Remaining in Minnesota, she married Michael (also a Macalester graduate) in 2006, became a US citizen, and has a senior position focused on talent management and performance with one of the largest international conglomerates. They have two children: Callum (14) and Zoë (12).

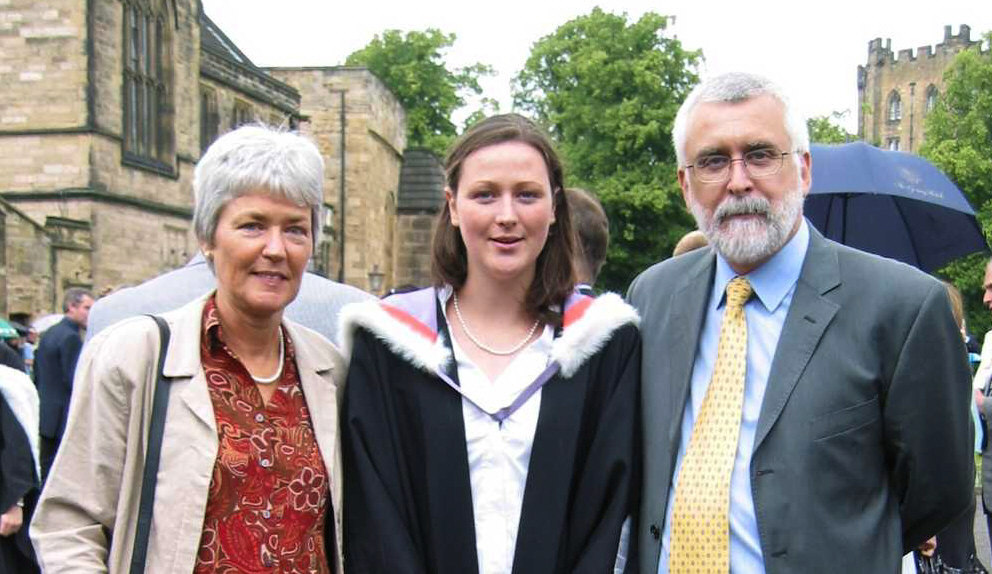

After a gap year, Philippa began her studies in Psychology at Durham University in 2000, graduating with a 2:i BSc degree three years later. Uncertain what path then to follow, she moved to Vancouver for a year, before having to return to the UK at short notice after the Canadian government refused to renew her work visa.

After a gap year, Philippa began her studies in Psychology at Durham University in 2000, graduating with a 2:i BSc degree three years later. Uncertain what path then to follow, she moved to Vancouver for a year, before having to return to the UK at short notice after the Canadian government refused to renew her work visa.

Post-graduation, outside Durham Cathedral.

She spent six months looking for a job, finally landing a research assistantship in the Brain, Performance and Nutrition Research Centre in the Department of Psychology at Northumbria University in Newcastle upon Tyne. After a couple of years she began her own PhD studies investigating the effects of bioactive lipids such as omega-3 fatty acids on cognition and brain health. She was awarded her PhD in December 2010.

She spent six months looking for a job, finally landing a research assistantship in the Brain, Performance and Nutrition Research Centre in the Department of Psychology at Northumbria University in Newcastle upon Tyne. After a couple of years she began her own PhD studies investigating the effects of bioactive lipids such as omega-3 fatty acids on cognition and brain health. She was awarded her PhD in December 2010.

Post-graduation with Steph and me, and Andi.

She’s the second psychologist in the family, with two more universities and two degrees (BSc, PhD) under her belt.

Philippa is now Director of the Brain, Performance and Nutrition Research Centre, and Associate Professor in Biological Psychology at Northumbria.

She married Andi in September 2010 (taking themselves off to New York to get married), and have two sons: Elvis (13) and Felix (11).

Two botanists and two psychologists. Who’d have thought it? Neither Hannah nor Philippa showed any interest in pursuing biology at degree level. Having two psychologists in the family we do wonder, from time-to-time, if we went wrong somewhere along the line.

Several weeks ago (or was it months?) UK Prime Minister Rishi Sunak (right) announced that his government would soon propose plans to reform secondary education for all pupils to study mathematics and English up to the age of 18, like many other countries.

Several weeks ago (or was it months?) UK Prime Minister Rishi Sunak (right) announced that his government would soon propose plans to reform secondary education for all pupils to study mathematics and English up to the age of 18, like many other countries.

qualification: the

qualification: the  This is what one headmistress, Victoria Hearn (right), Principal of state-assisted

This is what one headmistress, Victoria Hearn (right), Principal of state-assisted  So both were enrolled in the fee-paying

So both were enrolled in the fee-paying  Each had to complete a 4000 word essay based on independent research. Hannah’s history project was an analysis of the impact of the railways on the canals in mid-19th century England. Philippa made an analysis of

Each had to complete a 4000 word essay based on independent research. Hannah’s history project was an analysis of the impact of the railways on the canals in mid-19th century England. Philippa made an analysis of  I’m not a fan of talent shows like Britain’s Got Talent (BGT, or its US equivalent) or The X Factor, and

I’m not a fan of talent shows like Britain’s Got Talent (BGT, or its US equivalent) or The X Factor, and  The children were from

The children were from  The school was recently rated Good with some Outstanding features in its

The school was recently rated Good with some Outstanding features in its  Back in the day, Finstall First School (FFS) was less than a mile from home. It’s since moved to a new site just around the corner from our former home. Both our daughters Hannah and Philippa attended FFS whose head teacher was Mr Tecwyn Richards.

Back in the day, Finstall First School (FFS) was less than a mile from home. It’s since moved to a new site just around the corner from our former home. Both our daughters Hannah and Philippa attended FFS whose head teacher was Mr Tecwyn Richards. Aston Fields Middle School (AFMS) was even closer to home, and Hannah moved there when she was nine. The headmaster was Mr Barrie Dinsdale who, like his colleague at FFS, interacted so well with all the children.

Aston Fields Middle School (AFMS) was even closer to home, and Hannah moved there when she was nine. The headmaster was Mr Barrie Dinsdale who, like his colleague at FFS, interacted so well with all the children.

In Leek, my elder brother Edgar and I were enrolled at St Mary’s Catholic Primary School (now

In Leek, my elder brother Edgar and I were enrolled at St Mary’s Catholic Primary School (now

In September 1960, having passed my 11+ exam and won a scholarship to grammar school (that’s selective education for you), I attended

In September 1960, having passed my 11+ exam and won a scholarship to grammar school (that’s selective education for you), I attended  There’s been quite a bit in the news again recently about the value of a university education, after George Osbourne, the UK’s Chancellor of the Exchequer,

There’s been quite a bit in the news again recently about the value of a university education, after George Osbourne, the UK’s Chancellor of the Exchequer,