The same family – more or less. Dudmaston Hall has come down to the present residents (I don’t think ‘owners’ is the right term as the National Trust is involved in looking after property) through various familial inheritance twists and turns, not by direct ancestry. Landed gentry but not aristocrats.

Lying in the Severn Valley, a few miles south of Bridgnorth in Shropshire (but close to Worcestershire and Staffordshire county boundaries), Dudmaston Hall (well, the present building at least) dates from the late 17th century.

The main entrance on the north face

The main entrance on the north face

The courtyard

The south face

The south face

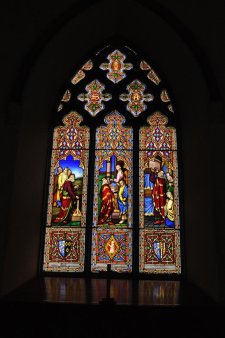

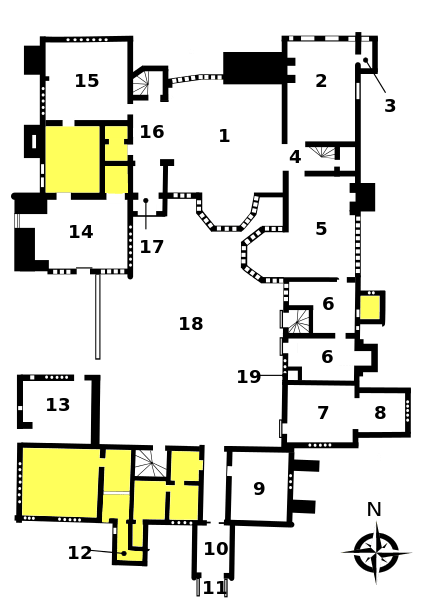

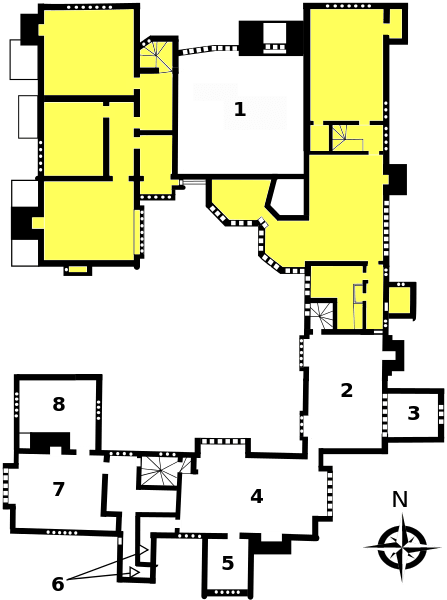

In many ways the house itself is quite modest. The ground floor entrance hall, library and oak study are open to the public. Access to the first floor is up a beautiful cantilevered staircase. Several bedrooms can be viewed – some of them still used as guest bedrooms! As the house is still lived in, photography is not permitted inside the house.

From 1966 until their deaths in the late 1990s, Dudmaston Hall was home to Sir George and Lady Rachel Labouchere (she had inherited the hall from her uncle Capt. Geoffrey Wolchyre-Whitmore, the family that had lived at Dudmaston for several generations). Sir George served in the diplomatic service during and after the Second World War, and was HM Ambassador in Spain from 1960-1966. He was also an avid collector of modern art (including many by Spanish artists), assembling – it’s reported – one the most important private collections in the country. Many of the best pieces are still displayed at Dudmaston today. I’m afraid I’m not really enthusiastic about modern art, but there was one bronze sculpture that really did take my fancy. Out of my budget range, though.

Lady Rachel Labouchere

Lady Rachel was a collector of botanical paintings, and many of those she collected are also on display, and of particular interest to Steph and me because of our botany backgrounds.

The gardens at Dudmaston are nothing to write home about, but the estate and park are extensive with opportunities for long walks – which we took full advantage of. Starting from the car park we headed towards the Big Pool that you can see on the map below (click on it for a larger image), over the Rustic Bridge, round the Dingle, across the dam, and following the path to the River Severn. Coming out of the woods on to a west-facing slope above the river, we could see the track of the Severn Valley Railway (a heritage line) on the other side. It would have been a great spot to watch the steam trains. But none came by, but once we’d headed back along the lake, we did hear a couple of locomotives whistling in the distance.

The lake has a high dam at the southern end, and is a haven for a large flock of Canada and greylag geese, that were swimming about in ‘family’ groups and happily honking to each other.

Crossing the Rustic Bridge

The Boat House

Looking south towards the Boat House and the Big Pool Dam

Dudmaston Hall, looking east across the Big Pool

While not the seat of a distinguished aristocratic family, Dudmaston Hall does have some important links with Britain’s industrial heritage. Lady Rachel was descended from the Darby family of Coalbrookdale (said to be the birthplace of the Industrial Revolution, less than 15 miles north of Dudmaston), where Abraham Darby developed iron smelting in the first decade of the 18th century and where, at Ironbridge, the world’s first bridge constructed from iron was built across the River Severn in 1779 (by Darby’s grandson, Abraham Darby III), using the same design principles as if it had been made from wood.

Charles Babbage, father of the computer who designed a mechanical Difference Machine in the early 19th century, was the brother-in-law of the Wolchyre-Whitmore owner of Dudmaston at that time. Babbage spent considerable periods at the hall. He also invented and installed the hall’s central heating system, and several of the metal vents are on display.

Charles Babbage, father of the computer who designed a mechanical Difference Machine in the early 19th century, was the brother-in-law of the Wolchyre-Whitmore owner of Dudmaston at that time. Babbage spent considerable periods at the hall. He also invented and installed the hall’s central heating system, and several of the metal vents are on display.

So while the visit to Dudmaston was, in some respects, a little disappointing, it was nice to get out and about, and enjoy a late summer day in the fresh air. Fortunately the journey to Dudmaston took little more than 30 minutes, being only 18 miles or so to the northwest of Bromsgrove.

On 24 June 2020, we made a farewell visit to Dudmaston. As more National Trust properties begin to open, we are taking the opportunity to grab tickets as and when we can. Last week we had a lovely walk around the park at Hanbury Hall.

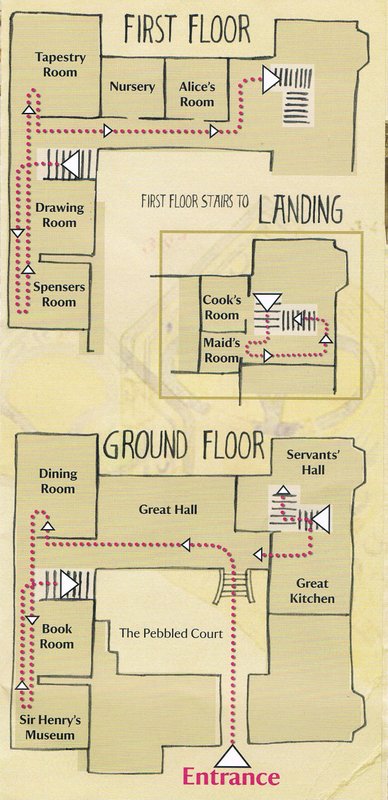

It was the hottest day of the year to date yesterday, but that didn’t deter us from heading to Dudmaston, and attempting a walk around the pool. In fact, when we arrived there, right on time at 13:30, we discovered that the NT had implemented a one-way system around the park, so once we’d started there was no turning back. We followed the route (shown by a red dotted line on the map below) through The Dingle, across the dam, and round the Big Pool back to the garden in front of the house.

Here is a link to a photo album of yesterday’s visit.

Despite dominating ‘England’ for only 400 years or so, the legacy of the Roman invasion and conquest of

Despite dominating ‘England’ for only 400 years or so, the legacy of the Roman invasion and conquest of

In many ways the house itself is quite modest. The ground floor entrance hall, library and oak study are open to the public. Access to the first floor is up a beautiful cantilevered staircase. Several bedrooms can be viewed – some of them still used as guest bedrooms! As the house is still lived in, photography is not permitted inside the house.

In many ways the house itself is quite modest. The ground floor entrance hall, library and oak study are open to the public. Access to the first floor is up a beautiful cantilevered staircase. Several bedrooms can be viewed – some of them still used as guest bedrooms! As the house is still lived in, photography is not permitted inside the house.

A few days ago, with a fair to promising weather forecast (it actually turned out much brighter and warmer than expected) we made another of our National Trust visits – this time to

A few days ago, with a fair to promising weather forecast (it actually turned out much brighter and warmer than expected) we made another of our National Trust visits – this time to