Lily May Jackson, née Healy, was born on 28 April 1908 in Shadwell in the East End of London, where her father, Martin Healy was a police officer with the Metropolitan Police. There were good Irish names in the family: Healy, Lenane, Phelan, Fitzgerald. After her father’s retirement from the Met, the family moved to Hook Road in Epsom, Surrey.

Lily May Jackson, née Healy, was born on 28 April 1908 in Shadwell in the East End of London, where her father, Martin Healy was a police officer with the Metropolitan Police. There were good Irish names in the family: Healy, Lenane, Phelan, Fitzgerald. After her father’s retirement from the Met, the family moved to Hook Road in Epsom, Surrey.

She died on 16 April 1992, just shy of her 84th birthday. Although christened as Lily, she was known as Lilian.

She was a beautiful woman, and she was my Mum.

This is the earliest photo I have of her. It was taken on 1 May 1915, and she turned seven just a week earlier. She is second from the right in the middle row.

The Healys

Mum was the second child of eight. Her elder sister Margaret died in 1927 just before her 21st birthday. I wonder how close Mum and Margaret were? Mum had already been in Canada for six months when Margaret died. I wonder if she knew how ill Margaret was before she emigrated? How must have Margaret’s death affected her? There’s no record of her returning to England for the funeral – that would have been simply too expensive.

Her four younger sisters and two brothers were: Ellen (1909-1980); Ivy Ann (known as Ann, 1912-1998); Martin Patrick (known as Pat, 1914-2012); Eileen (1918-1994); John (1919-1994); and Irene Bridget (known as Bridie, 1921-1993).

I have no recollection of ever having met Ellen. I met Pat twice (in about 1955 and 1965 or so), and Mum reconnected with Ann in the mid-1960s and remained in contact afterwards. In about 1970 Bridie came over to the UK – probably the first time since she emigrated after the war, and that was the only time I met her. On the other hand Eileen and John were always in close contact with our family. In early 1955 or thereabouts – but before

Eileen married Roy in May 1955 – I spent a week or more with Eileen at the family home in Hook Road, Epsom, Surrey. During that stay we visited John and Barbara at Worcester Park close to Epsom where John had his own gentleman’s outfitters business, and he gave me a red plaid tie. I wore that next day on a trip into London. Then she took me and my cousin Chris (born 1944), John and Barbara’s son, to Southend-on-Sea to visit Pat. I think he was a policeman there.

Eileen married Roy in May 1955 – I spent a week or more with Eileen at the family home in Hook Road, Epsom, Surrey. During that stay we visited John and Barbara at Worcester Park close to Epsom where John had his own gentleman’s outfitters business, and he gave me a red plaid tie. I wore that next day on a trip into London. Then she took me and my cousin Chris (born 1944), John and Barbara’s son, to Southend-on-Sea to visit Pat. I think he was a policeman there.

I guess Mum lost contact with some of her family because there was no longer the ‘focus’ of parents bringing everyone together from time-to-time. My grandmother had died in 1952 followed by granddad Healy in October 1954. I only met my grandmother once – I was very small and vaguely remember seeing this old lady in bed in a care home.

I guess Mum lost contact with some of her family because there was no longer the ‘focus’ of parents bringing everyone together from time-to-time. My grandmother had died in 1952 followed by granddad Healy in October 1954. I only met my grandmother once – I was very small and vaguely remember seeing this old lady in bed in a care home.

Eileen was quite a regular visitor as I was growing up in the 50s and 60s. She often needed hospital treatment and stayed with us to recuperate on one occasion after an operation at a hospital in The Potteries. John and Barbara became lifelong friends with my Dad’s elder sister Wynne and her family, and we’d often meet up on holiday in Saundersfoot in Pembrokeshire.

L to R: Wynne (Dad’s elder sister), Barbara Healy, Dad, Ed (my elder brother), Cyril Moore (Wynne’s husband), Mum, John Healy, me, Diana Moore (cousin), Chris Healy (cousin), Mary (Diana’s closest friend) – enjoying the beach at Saundersfoot, c. 1961

A new life across the Atlantic

Mum emigrated to Montreal, Canada in 1927 at the age of 19 to work as a nanny for a Mr and Mrs de Lothiere; then she moved to New Haven, Connecticut in 1931 and shortly afterwards to New Jersey in the USA. There she trained as a nurse and graduated in May 1936 from The Hospital and Home for Crippled Children, Newark, looking after children suffering from polio and tuberculosis. I wonder if it was exposure there to tuberculosis that led to me acquiring immunity to this terrible disease? I say ‘shortly afterwards’ about her move to New Jersey because Mum once told me about the ‘Crime of the Century‘ in March 1932 when the son of famous aviator Charles Lindbergh was kidnapped, and she remembered all the police activity. She also knew New York before the Empire State Building was completed. We don’t know exactly what Mum did between leaving school and emigrating, but the manifest of the Cunard liner RMS Andania on which she sailed to Quebec from Southampton listed her as a ‘stenographer’.

Becoming a wife and mother

Mum first met my Dad on board a Cunard White Star liner in 1934 (probably the RMS Aquitania on which he served as a photographer for many of his transatlantic crossings) when she returned to England to see her parents and, with two friends asked him to take their photo. The rest is history!

They were married on 28 November 1936 at St Joseph’s Roman Catholic church in Epsom, Surrey, less than a fortnight before the abdication of Edward VIII on 10 December.

L to R: Alice Jackson, Thomas Jackson (Dad’s parents), Rebecca Jackson (Dad’s younger sister), Ernest Bettley (Dad’s best man and a longtime shipmate), Dad, Mum, Eileen (Mum’s second youngest sister), Martin Healy, Ellen Healy (Mum’s parents), photo taken at Hook Road, Epsom, Surrey.

Mum and Dad made home in Bath in Somerset and my eldest bother Martin was born there in 1939, just three days before war was declared on Germany. They moved to Congleton before 1941 because my sister Margaret was born there in January 1941. Dad served in the Royal Navy during the war, and Mum, Martin and Margaret lived some of the time with the Jackson in-laws in Hollington in Derbyshire. After the war, they returned to Congleton where Ed was born in 1946, and I followed in November 1948. In April 1956 we moved to Leek where Dad opened his own photographic business.

Mum and Dad were devoted to each other. They enjoyed a shared love of ballroom dancing, of whist, and were both very active in local groups in Leek, Mum with the Townswomen’s Guild (and amateur dramatics) and Dad with the Leek Camera Club.

Most years they would take a camping holiday in Wales (often with Ed and me in tow) mostly under canvas, but for a couple of years in a caravan. From the mid-60s they ventured more into Scotland on their own.

After Dad retired in 1976 and they sold the photographic business, Mum and Dad fulfilled a long-held ambition: to see the Grand Canyon. And so, 40 years after they had left the USA, they returned, visiting the West Coast, Yosemite, the Grand Canyon, and all places in between, and up to Alberta where my brother Ed lives.

Sadly Mum was widowed in 1980, but she continue to live, alone, in Leek. In late 1990 however, she suffered a stroke and was not expected to live more than a couple of days. But she did, and eventually moved into a nursing home in Newport near to where my sister Margaret and her husband Trevor then lived. I saw my Mum for the last time in June 1991 shortly before I moved to the Philippines to work at the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI). In April 1992, Steph, our two daughters Hannah and Philippa, and me had just arrived for an Easter long-weekend away at the beach when we received the news that Mum had passed away peacefully in her sleep the night before. I then made arrangements to fly back to the UK for her funeral. Eileen and Roy also attended the funeral. A couple of years later, Eileen’s health took a turn for the worse, and was hospitalized. It was early November 1994 that I happened to be in London on a work-related trip for IRRI and took the opportunity of visiting Eileen and Roy in Epsom. Eileen passed away about three weeks later.

I have long since stopped grieving for my Mum – or for my Dad for that matter. Martin, Margaret, Ed and me are left with beautiful memories of our wonderful parents. Fortunately we also have a photographic legacy as well to support those memories – that fade just a little more with each passing year.

I had always wondered how Great Britain became embroiled in a European war that was started four years earlier in August 1914 following the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand in Saravejo at the end of June. Just a month later Europe was consumed in a conflagration that came to be known as World War One or the Great War. How did an event hundreds of miles away in Bosnia drag Great Britain into war? Well, a couple of months I did

I had always wondered how Great Britain became embroiled in a European war that was started four years earlier in August 1914 following the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand in Saravejo at the end of June. Just a month later Europe was consumed in a conflagration that came to be known as World War One or the Great War. How did an event hundreds of miles away in Bosnia drag Great Britain into war? Well, a couple of months I did  So what changed in 1918? How did the war come to an end. I have just finished reading an excellent review of the last months of the conflict, A Hundred Days – The end of the Great War* by Nick Lloyd, Senior Lecturer in Defence Studies at King’s College London (based at the Joint Services Command and Staff College in Wiltshire).

So what changed in 1918? How did the war come to an end. I have just finished reading an excellent review of the last months of the conflict, A Hundred Days – The end of the Great War* by Nick Lloyd, Senior Lecturer in Defence Studies at King’s College London (based at the Joint Services Command and Staff College in Wiltshire). Spring! Probably my favorite season. And for me, yellow is the color of Spring.

Spring! Probably my favorite season. And for me, yellow is the color of Spring.

![From: http://media.photobucket.com/user/toxicwanderer/media/Boring-meeting.jpg.html?filters[term]=boring%20meeting&filters[primary]=images&filters[secondary]=videos&sort=1&o=0](https://mikejackson1948.blog/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/boring-meeting.jpg?w=474) I’m not a very good committee sort of person, and I have quite a low tolerance level for poorly planned and chaired meetings. A particular grouch of mine is an unrealistic agenda. I remember one meeting more than 15 years ago that had an agenda with 14 or more items for discussion. After almost three hours we’d only worked our way through a couple of these. I don’t think we ever did get back to some of the points – although they must have merited some attention having been included in the first place. Better for the meeting chair to seek endorsement of various options by email than wasting everyone’s time (and at what dollar cost) sitting around a table getting nowhere. It’s no wonder that some organizations have taken radical measures in the way they organize meetings – and who they invite. Oh, and woe betide a meeting convener who hadn’t organized coffee and cookies!

I’m not a very good committee sort of person, and I have quite a low tolerance level for poorly planned and chaired meetings. A particular grouch of mine is an unrealistic agenda. I remember one meeting more than 15 years ago that had an agenda with 14 or more items for discussion. After almost three hours we’d only worked our way through a couple of these. I don’t think we ever did get back to some of the points – although they must have merited some attention having been included in the first place. Better for the meeting chair to seek endorsement of various options by email than wasting everyone’s time (and at what dollar cost) sitting around a table getting nowhere. It’s no wonder that some organizations have taken radical measures in the way they organize meetings – and who they invite. Oh, and woe betide a meeting convener who hadn’t organized coffee and cookies! Maybe you’re a frequent flyer. Maybe not. How many of the flights you have taken were memorable? I hardly remember one flight from another (unless they were the two occasions when I was invited on to the flight-deck, on LH and EK flights, for the landing at Manila (MNL, RPLL). On the other hand, how many airport experiences – good or bad (mostly bad) – have you experienced?

Maybe you’re a frequent flyer. Maybe not. How many of the flights you have taken were memorable? I hardly remember one flight from another (unless they were the two occasions when I was invited on to the flight-deck, on LH and EK flights, for the landing at Manila (MNL, RPLL). On the other hand, how many airport experiences – good or bad (mostly bad) – have you experienced? You bet!

You bet!

I have tried durian on just one occasion, and that was once too often. You definitely have to get past the smell in order to savor the fruit. I found the fruit extremely rich and ‘custardy’, that left me with a lingering aftertaste for a couple of days and, unfortunately, ferocious heartburn.

I have tried durian on just one occasion, and that was once too often. You definitely have to get past the smell in order to savor the fruit. I found the fruit extremely rich and ‘custardy’, that left me with a lingering aftertaste for a couple of days and, unfortunately, ferocious heartburn. Then there’s the

Then there’s the

I’ve just begun reading Anchee Min’s memoir

I’ve just begun reading Anchee Min’s memoir

4 August 1914. Britain declares war on Germany, joining the Entente Powers Russia and France a couple of days after war had already been declared between them and the Central Powers, Germany and Austria-Hungary.

4 August 1914. Britain declares war on Germany, joining the Entente Powers Russia and France a couple of days after war had already been declared between them and the Central Powers, Germany and Austria-Hungary. I’ve just finished reading Sean McMeekin’s analysis*, published last year, of the lead up to the war from the initial incident – the ‘spark that set Europe aflame’ only a month later: the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand (and his wife of a morgantic marriage, Sophie) on the morning of Sunday 28 June in Sarajevo, Bosnia-Herzegovina.

I’ve just finished reading Sean McMeekin’s analysis*, published last year, of the lead up to the war from the initial incident – the ‘spark that set Europe aflame’ only a month later: the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand (and his wife of a morgantic marriage, Sophie) on the morning of Sunday 28 June in Sarajevo, Bosnia-Herzegovina.

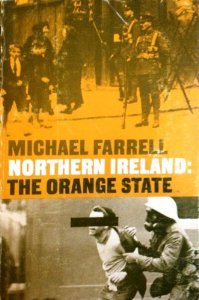

Northern Ireland: The Orange State is a comprehensive account of how partition and its aftermath shaped political, cultural and economic development in Northern Ireland, and how the domination of the Catholics by the majority Protestant Unionists or Loyalists was bound – eventually – to culminate in

Northern Ireland: The Orange State is a comprehensive account of how partition and its aftermath shaped political, cultural and economic development in Northern Ireland, and how the domination of the Catholics by the majority Protestant Unionists or Loyalists was bound – eventually – to culminate in