What’s in a name? Well, not a lot it seems when it comes to crop germplasm. It’s a particular ‘bee in the bonnet’ I’ve had for many years.

We use names for everything. In the right context, a name is a ‘shorthand’ as it were for anything we can describe. In the natural world, we use a strict system of nomenclature (in Latin of all languages) – seemingly, to the non-specialist, continually and bewilderingly revised. Most plants and animals also have common names, in the vernacular, for everyday use. But while scientific nomenclature follows strict rules, the same can’t be said for common names.

Stretching an analogy

However, let me start by presenting you with an analogy. Take these two illustrious individuals for example.

We share the same name, though I doubt anyone would confuse us. Certainly not based on our phenotypes – what we look like. In any case, I’m WYSIWYG. Our ‘in common’ name implies no relationship whatsoever.

What about identical monozygotic twins, such as Marian and Val Brown? Dressing alike, they became celebrities in their adopted city of San Francisco from the 1970s until their deaths. Same genetics, but different names.

What about identical monozygotic twins, such as Marian and Val Brown? Dressing alike, they became celebrities in their adopted city of San Francisco from the 1970s until their deaths. Same genetics, but different names.

Maybe I’m stretching the analogy too much. I just want to hammer home the idea that sharing the same name should not imply common genetics. And different names might mask common genetics.

Naming crop varieties

So let’s turn to the situation in crop germplasm resources.

I had found in my doctoral research that apparently identical Andean potato varieties – based on morphology and tuber protein profiles – might have the same name or, if sourced from different parts of the country, completely different names given by local communities. And it also was not uncommon to find potatoes that looked very different having the same name – often based on some particular morphological characteristic. When we collected rice varieties in Laos during the 1990s, we described how Laotian farmers name their varieties [1].

During the 1980s my University of Birmingham colleague Brian Ford-Lloyd and I, with Susan Juned, studied somaclonal variation in the potato cv. Record. We received a sample of 50 or so tubers of Record, and fortunately decided to give each individual tuber its own ID number. The number of somaclones generated from each tuber was very different, and we attributed this to the fact that seed potatoes in the UK are ultimately produced from different tissue culture stocks. This suggested that there had been selection during culture for types that responded better to tissue culture per se [2]. The implication of course is that potato cv. Record (and many others) is actually an amalgam of many minor variants. I recently read a paper about farmer selection of somaclonal variants of taro (Colocasia esculenta) and cassava (Manihot esculenta) in Vanuatu.

Dropping the ID

But there is a trend – and a growing trend at that – to rely too much on names when it comes to crop germplasm. What I’ve found is that users of rice germplasm (and especially if they are rice breeders) rely too heavily on the variety name alone. And I’d be very interested to know if curators of other germplasm collections experience the same issue.

Why does this matter, and how to resolve this dilemma?

During the 1990s when we were updating the inventory of samples (i.e. accessions) in the International Rice Genebank Collection at IRRI, we discovered there were multiple accessions of several IRRI varieties, like IR36, IR64 or IR72. I’m not sure why they had been put into the collection, but they had been sourced from a number of countries around Asia.

We decided to carefully check whether the accessions with the same name (but different accession numbers) were indeed the same. So we planted a field trial to carefully measure a whole range of traits, not just morphological, but also some growth ones such as days to flowering. I should hasten to add that included among the accessions of each ‘variety’ was one accession added to the genebank collection at the time the variety had been released – the original sample of each.

We were surprised to discover that there were significant differences between accessions of a variety. I raised this issue with then head of IRRI’s plant breeding department, the eminent Indian rice breeder Dr Gurdev Khush. Rather patronizingly, I thought, he dismissed my concerns as irrelevant. As a rice breeder with several decades of experience and the breeder responsible for their release, he assured me that he ‘knew’ what the varieties should look like and how they ought to perform. I think he regarded me as a ‘rice parvenu’.

It seemed to me that farmers had made selections from within these varieties that had been grown in different environments, but then had kept the same name. So it was not a question of ‘IR36 is IR36 is IR36‘. Maybe there was still some measure of segregation at the time of original release in an otherwise genetically uniform variety.

I have a hunch that some of the equivocal results from different labs during the early rice genome research using the variety Nipponbare can be put down to the use of different seed sources of Nipponbare.

Germplasm requests for seeds from the International Rice Genebank Collection often came by variety name, like Nipponbare or Azucena for example. But which Nipponbare or Azucena, since the there are multiple samples of these and many others in the collection?

What I also discovered is that when it comes to publication of their research, many rice scientists frequently omit to include the germplasm accession numbers – the unique IDs. Would ‘discard’ be too strong an indictment?

I was reviewing a manuscript just a few days ago, of a study that included rice germplasm from IRRI and another genebank. There was a list of the germplasm, by accession/variety name but not the accession number. Now how irresponsible is that? If someone else wanted to repeat or extend that study (and there are so many other instances of the same practice) how would they know which actual samples to choose? There is just this belief – and it beggars belief – that germplasm samples with the same name are genetically the same. However, we know that is not the case. It takes no effort to provide the comprehensive list of germplasm accession numbers alongside variety names.

Accession numbers should be required

I’m on the editorial board of Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution. I have proposed to the Editor-in-Chief that any manuscript that does not include the germplasm accession numbers (or provenance of the germplasm used) should be automatically sent back to the authors for revision, and even rejected if this information cannot be provided, whatever the quality of the science! Listing the germplasm accession numbers should become a requirement for publication.

Draconian response? Pedantic even? I don’t think so, since it’s a fundamental germplasm management and use issue.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

[1] Appa Rao, S., C. Bounphanousay, J.M. Schiller & M.T. Jackson, 2002. Naming of traditional rice varieties by farmers in the Lao PDR. Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution 49, 83-88.

[2] Juned, S.A., M.T. Jackson & B.V. Ford-Lloyd, 1991. Genetic variation in potato cv. Record: evidence from in vitro “regeneration ability”. Annals of Botany 67, 199-203.

Humble? Boiled, mashed, fried, roast, chipped or prepared in many other ways, the potato is surely the King of Vegetables. And for 20 years in the 1970s and 80s, potatoes were the focus of my own research.

Humble? Boiled, mashed, fried, roast, chipped or prepared in many other ways, the potato is surely the King of Vegetables. And for 20 years in the 1970s and 80s, potatoes were the focus of my own research.

You bet!

You bet!

The Irish connection

The Irish connection My English teacher at high school, Frank Byrne, had family from Co. Roscommon, and on the syllabus the year I took my exams was the poetry of Nobel Laureate

My English teacher at high school, Frank Byrne, had family from Co. Roscommon, and on the syllabus the year I took my exams was the poetry of Nobel Laureate  My Irish grandparents, Martin Healy and Ellen née Lenane, hailed from Co. Kilkenny and Co. Waterford, respectively. Like many young Irishmen, my grandfather – at the age of almost 16 it seems – joined the British Army (controversially, as seen through nationalist eyes), serving in the Royal Irish Regiment for 12 years, seeing service in India (in the North West Frontier) from 1894-99, and also in South Africa during the Boer War for almost three years from November 1899. He took part in the

My Irish grandparents, Martin Healy and Ellen née Lenane, hailed from Co. Kilkenny and Co. Waterford, respectively. Like many young Irishmen, my grandfather – at the age of almost 16 it seems – joined the British Army (controversially, as seen through nationalist eyes), serving in the Royal Irish Regiment for 12 years, seeing service in India (in the North West Frontier) from 1894-99, and also in South Africa during the Boer War for almost three years from November 1899. He took part in the

in his seminal The History and Social Influence of the Potato (originally published in 1949). For 20 years from 1971 my

in his seminal The History and Social Influence of the Potato (originally published in 1949). For 20 years from 1971 my

Hindsight is a wonderful thing. Although I spent more than 20 years studying potatoes – in a variety of guises – that had not been my first choice. I originally wanted to become the world’s lentil expert.

Hindsight is a wonderful thing. Although I spent more than 20 years studying potatoes – in a variety of guises – that had not been my first choice. I originally wanted to become the world’s lentil expert. Interestingly, unknown to Trevor and me, renowned Israeli expert on crop evolution Professor Daniel Zohary (of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem) had been working on the same problem, and published his results in Economic Botany in 1972 [1], which essentially confirmed the conclusions I’d reached a year earlier.

Interestingly, unknown to Trevor and me, renowned Israeli expert on crop evolution Professor Daniel Zohary (of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem) had been working on the same problem, and published his results in Economic Botany in 1972 [1], which essentially confirmed the conclusions I’d reached a year earlier.

(then with the USDA regional potato germplasm project in Sturgeon Bay, Wisconsin, and later to join CIP in July 1973 as head of the breeding and genetics department), ethnobotanist and taxonomist

(then with the USDA regional potato germplasm project in Sturgeon Bay, Wisconsin, and later to join CIP in July 1973 as head of the breeding and genetics department), ethnobotanist and taxonomist  and potato breeder

and potato breeder

At first, there were few internationally-recruited staff, but throughout 1973, the staff increased quite rapidly. Rainer Zachmann, a German plant pathologist working on Rhizoctonia solani, joined in February, followed by Julia Guzman, a late blight specialist from Colombia; Parviz Jatala, a nematologist from Iran; Ray Meyer, an agronomist from the USA; and Dick Wurster as head of the Outreach Dept. , among others. Dick had been working in Uganda prior to joining CIP.

At first, there were few internationally-recruited staff, but throughout 1973, the staff increased quite rapidly. Rainer Zachmann, a German plant pathologist working on Rhizoctonia solani, joined in February, followed by Julia Guzman, a late blight specialist from Colombia; Parviz Jatala, a nematologist from Iran; Ray Meyer, an agronomist from the USA; and Dick Wurster as head of the Outreach Dept. , among others. Dick had been working in Uganda prior to joining CIP.

My fiancée

My fiancée  When the late

When the late

Here is the list of University of Birmingham PhD students who worked on potatoes, as far as I can remember. All of them from 1975 (with the exception of Ian Gubb) had also attended the MSc course on genetic resources:

Here is the list of University of Birmingham PhD students who worked on potatoes, as far as I can remember. All of them from 1975 (with the exception of Ian Gubb) had also attended the MSc course on genetic resources: Richard Lester (UK), 1962. Taught at Makerere University in Uganda, before joining the Dept. of Botany at Birmingham in 1969. Retired in 2002, and died in 2006. Studied the biochemical systematics of Mexican wild Solanum species. The species Solanum lesteri is named after him.

Richard Lester (UK), 1962. Taught at Makerere University in Uganda, before joining the Dept. of Botany at Birmingham in 1969. Retired in 2002, and died in 2006. Studied the biochemical systematics of Mexican wild Solanum species. The species Solanum lesteri is named after him.

Katsuo Armando Okada (Argentina), 1970 (?). Retired. Was with IBPGR for a while in the 1980s (?) in Colombia. Studied the origin of Solanum x rechei from Argentina.

Katsuo Armando Okada (Argentina), 1970 (?). Retired. Was with IBPGR for a while in the 1980s (?) in Colombia. Studied the origin of Solanum x rechei from Argentina.

David Astley (UK), 1975. Became the curator of the vegetable genebank at Wellesbourne (now the

David Astley (UK), 1975. Became the curator of the vegetable genebank at Wellesbourne (now the

Peter Schmiediche (Germany), 1977. He continued working with CIP as a potato breeder (for resistance to bacterial wilt), and was later CIP’s regional leader based in Indonesia. Now retired and sharing his time between Texas (where his children settled) and his native Berlin. Studied the bitter potatoes Solanum x juzepczukii (3x) and S. x curtilobum (5x). Joint with CIP and Roger Rowe.

Peter Schmiediche (Germany), 1977. He continued working with CIP as a potato breeder (for resistance to bacterial wilt), and was later CIP’s regional leader based in Indonesia. Now retired and sharing his time between Texas (where his children settled) and his native Berlin. Studied the bitter potatoes Solanum x juzepczukii (3x) and S. x curtilobum (5x). Joint with CIP and Roger Rowe. Carlos Arbizu (Peru), 1990. An expert on minor Andean tuber crops, he came from the University of Ayacucho. Spent time working in the germplasm program at CIP. Studied the origin and value of resistance to spindle tuber viroid in Solanum acaule. Joint with CIP and principal virologist Luis Salazar (who gained his PhD while studying at the

Carlos Arbizu (Peru), 1990. An expert on minor Andean tuber crops, he came from the University of Ayacucho. Spent time working in the germplasm program at CIP. Studied the origin and value of resistance to spindle tuber viroid in Solanum acaule. Joint with CIP and principal virologist Luis Salazar (who gained his PhD while studying at the  Susan Juned (UK), 1994. Now a sustainable technology consultant, Sue is an active local government councillor, and has stood for election to parliament on a couple of occasions for the Liberal Democrats. Studied

Susan Juned (UK), 1994. Now a sustainable technology consultant, Sue is an active local government councillor, and has stood for election to parliament on a couple of occasions for the Liberal Democrats. Studied  David Tay (Malaysia), 2000. He worked in Australia and then was Director of the USDA Ornamental Plant Germplasm Center in Columbus, Ohio, but returned to CIP as head of the genetic resources unit in 2007. He’s now left CIP. I think he worked on diploid cultivated species. Joint with CIP. Not sure why his PhD is dated 2000, as he’d been in CIP in the late 70s.

David Tay (Malaysia), 2000. He worked in Australia and then was Director of the USDA Ornamental Plant Germplasm Center in Columbus, Ohio, but returned to CIP as head of the genetic resources unit in 2007. He’s now left CIP. I think he worked on diploid cultivated species. Joint with CIP. Not sure why his PhD is dated 2000, as he’d been in CIP in the late 70s.

Roger Rowe, who had been in charge of the

Roger Rowe, who had been in charge of the  I can’t remember why I had always wanted to visit Peru. All I know is that since I was a small boy, Peru had held a big fascination for me. I used to spend time leafing through an atlas, and spending most time looking at the maps of South America, especially Peru. And I promised myself (in the way that you do when you’re small, and can’t see how it would ever happen) that one day I would visit Peru.

I can’t remember why I had always wanted to visit Peru. All I know is that since I was a small boy, Peru had held a big fascination for me. I used to spend time leafing through an atlas, and spending most time looking at the maps of South America, especially Peru. And I promised myself (in the way that you do when you’re small, and can’t see how it would ever happen) that one day I would visit Peru. To cut a long story short, I didn’t go in 1971, but landed in Lima at the beginning of January 1973 after a long and gruelling flight on B.O.A.C. from London via Antigua (in the Caribbean), Caracas, and Bogotá.

To cut a long story short, I didn’t go in 1971, but landed in Lima at the beginning of January 1973 after a long and gruelling flight on B.O.A.C. from London via Antigua (in the Caribbean), Caracas, and Bogotá. First there is the geography: the long coastal desert stretching north from Lima to the border with Ecuador, and south to Chile where it merges with the Atacama Desert. It hardly ever rains on the coast, but the sea mists that are prevalent during the months of July-September do provide sufficient moisture in some parts (lomas) to develop quite a rich flora.

First there is the geography: the long coastal desert stretching north from Lima to the border with Ecuador, and south to Chile where it merges with the Atacama Desert. It hardly ever rains on the coast, but the sea mists that are prevalent during the months of July-September do provide sufficient moisture in some parts (lomas) to develop quite a rich flora.  The Andes mountains take your breath away with their magnificence. The foothills begin just a few kilometers from the coast, and the mountains rise to their highest point in Huascarán (6,768 m), the fourth highest mountain in the western hemisphere.

The Andes mountains take your breath away with their magnificence. The foothills begin just a few kilometers from the coast, and the mountains rise to their highest point in Huascarán (6,768 m), the fourth highest mountain in the western hemisphere.

And there is also considerable evidence for the range of plants and animals that these peoples domesticated: the potato, beans, cotton, peanut, and llamas to name but a few. Fortunately this rich history has been preserved and Lima boasts some of the best museums in the world.

And there is also considerable evidence for the range of plants and animals that these peoples domesticated: the potato, beans, cotton, peanut, and llamas to name but a few. Fortunately this rich history has been preserved and Lima boasts some of the best museums in the world. From north to south, different peoples wear different dress. In Cajamarca, the typical dress is a tall straw hat and a russet-colored poncho. In central Peru, the women wear hats like the one shown in the photo on the right. The south of Peru, around Cuzco and Puno is more traditional still.

From north to south, different peoples wear different dress. In Cajamarca, the typical dress is a tall straw hat and a russet-colored poncho. In central Peru, the women wear hats like the one shown in the photo on the right. The south of Peru, around Cuzco and Puno is more traditional still. Peru is also a country of great handicrafts – from the leather goods made in Lima, to the carved gourds or mate burilado, clay figures of farmers or religious effigies, to a wealth of brightly colored textiles.

Peru is also a country of great handicrafts – from the leather goods made in Lima, to the carved gourds or mate burilado, clay figures of farmers or religious effigies, to a wealth of brightly colored textiles.

I joined CIP in January 1973 as Associate Taxonomist, charged with the task of collecting potato varieties and helping them to maintain the large germplasm collection, that grew to at least 15,000 separate entries (or clonal accessions), but was reduced to a more manageable number through the elimination of duplicate samples. The germplasm collection was planted each year from October through April, coinciding with the most abundant rains, in the field in Huancayo, central Peru at an altitude of more than 3,100 meters.

I joined CIP in January 1973 as Associate Taxonomist, charged with the task of collecting potato varieties and helping them to maintain the large germplasm collection, that grew to at least 15,000 separate entries (or clonal accessions), but was reduced to a more manageable number through the elimination of duplicate samples. The germplasm collection was planted each year from October through April, coinciding with the most abundant rains, in the field in Huancayo, central Peru at an altitude of more than 3,100 meters.

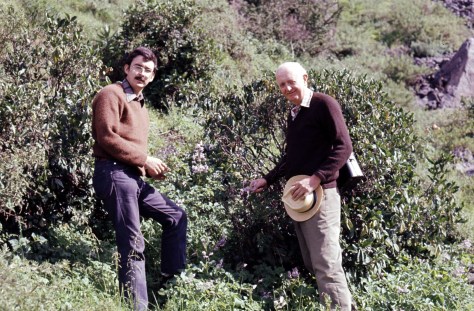

that endeavour. In May 1973 I joined my colleague Zosimo Huaman to collect potatoes in the Departments of Ancash and La Libertad, to the north of Lima. The highest mountains in Peru are found in Ancash, and our route took us through into the

that endeavour. In May 1973 I joined my colleague Zosimo Huaman to collect potatoes in the Departments of Ancash and La Libertad, to the north of Lima. The highest mountains in Peru are found in Ancash, and our route took us through into the

of a minor Andean tuber crop called oca (Oxalis tuberosa). We went to the village of Cuyo Cuyo, more than 100 km north of Puno in southern Peru. Dropping down from the altiplano, the road hugs the sides of the valley, and is often blocked by landslides (a very common occurrence throughout Peru in the rainy season). Along the way – and due to the warmer air rising from the selva (jungle) to the east – the vegetation is quite luxurious in places, as the white begonia below shows (the flowers were about 8 cm in diameter). Eventually the valley opens out, with terraces on all sides. These terraces (or andenes) are ancient structures constructed by the Incas to make the valley more productive.

of a minor Andean tuber crop called oca (Oxalis tuberosa). We went to the village of Cuyo Cuyo, more than 100 km north of Puno in southern Peru. Dropping down from the altiplano, the road hugs the sides of the valley, and is often blocked by landslides (a very common occurrence throughout Peru in the rainy season). Along the way – and due to the warmer air rising from the selva (jungle) to the east – the vegetation is quite luxurious in places, as the white begonia below shows (the flowers were about 8 cm in diameter). Eventually the valley opens out, with terraces on all sides. These terraces (or andenes) are ancient structures constructed by the Incas to make the valley more productive.

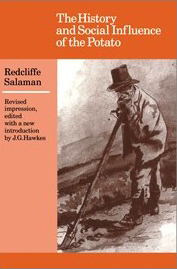

John Gregory ‘Jack’ Hawkes – botanist, educator, and visionary – was born in Bristol in 1915. After completing his secondary education at Cheltenham Grammar School in 1934, he won a place at Christ’s College, University of Cambridge, graduating with a BA (Natural Sciences, first class honours) in 1937. His MA was awarded in 1938, and he completed his PhD in 1941 under the supervision of the noted potato breeder and historian, Dr Redcliffe N Salaman FRS. The university awarded Jack the ScD degree in 1957.

John Gregory ‘Jack’ Hawkes – botanist, educator, and visionary – was born in Bristol in 1915. After completing his secondary education at Cheltenham Grammar School in 1934, he won a place at Christ’s College, University of Cambridge, graduating with a BA (Natural Sciences, first class honours) in 1937. His MA was awarded in 1938, and he completed his PhD in 1941 under the supervision of the noted potato breeder and historian, Dr Redcliffe N Salaman FRS. The university awarded Jack the ScD degree in 1957. On graduation in 1937 Jack successfully applied for the position of assistant to Dr PS Hudson, Director of the Imperial Bureau of Plant Breeding and Genetics in Cambridge, for an expedition to Lake Titicaca in the South American Andes. In the event this expedition did not materialize due to Hudson’s poor health, but a more comprehensive expedition was then planned for 1939, led by EK Balls, a professional plant collector. Thus began Jack’s lifelong interest in ‘the humble spud’.

On graduation in 1937 Jack successfully applied for the position of assistant to Dr PS Hudson, Director of the Imperial Bureau of Plant Breeding and Genetics in Cambridge, for an expedition to Lake Titicaca in the South American Andes. In the event this expedition did not materialize due to Hudson’s poor health, but a more comprehensive expedition was then planned for 1939, led by EK Balls, a professional plant collector. Thus began Jack’s lifelong interest in ‘the humble spud’.

In addition to his lifelong research on potatoes, Jack also spearheaded scientific interest in the Solanaceae plant family that also includes tomato, tobacco, chili peppers, and eggplant, and many species with pharmaceutical properties. With colleagues at Birmingham in the late 1950s he developed serological methods to study relationships between potato species. He was also one of the leading lights to produce a computer-mapped Flora of Warwickshire, a first of its kind, published in 1971.

In addition to his lifelong research on potatoes, Jack also spearheaded scientific interest in the Solanaceae plant family that also includes tomato, tobacco, chili peppers, and eggplant, and many species with pharmaceutical properties. With colleagues at Birmingham in the late 1950s he developed serological methods to study relationships between potato species. He was also one of the leading lights to produce a computer-mapped Flora of Warwickshire, a first of its kind, published in 1971.