I started this post exactly a year ago with the intention of chronicling what Steph and I have been up to during 2025, month by month. In this respect, this post is unlike any of the others I’ve written over the past 13 years. Certainly this post reflects how busy we’ve been, and how, in our late 70s, it is important to keep active in retirement, .

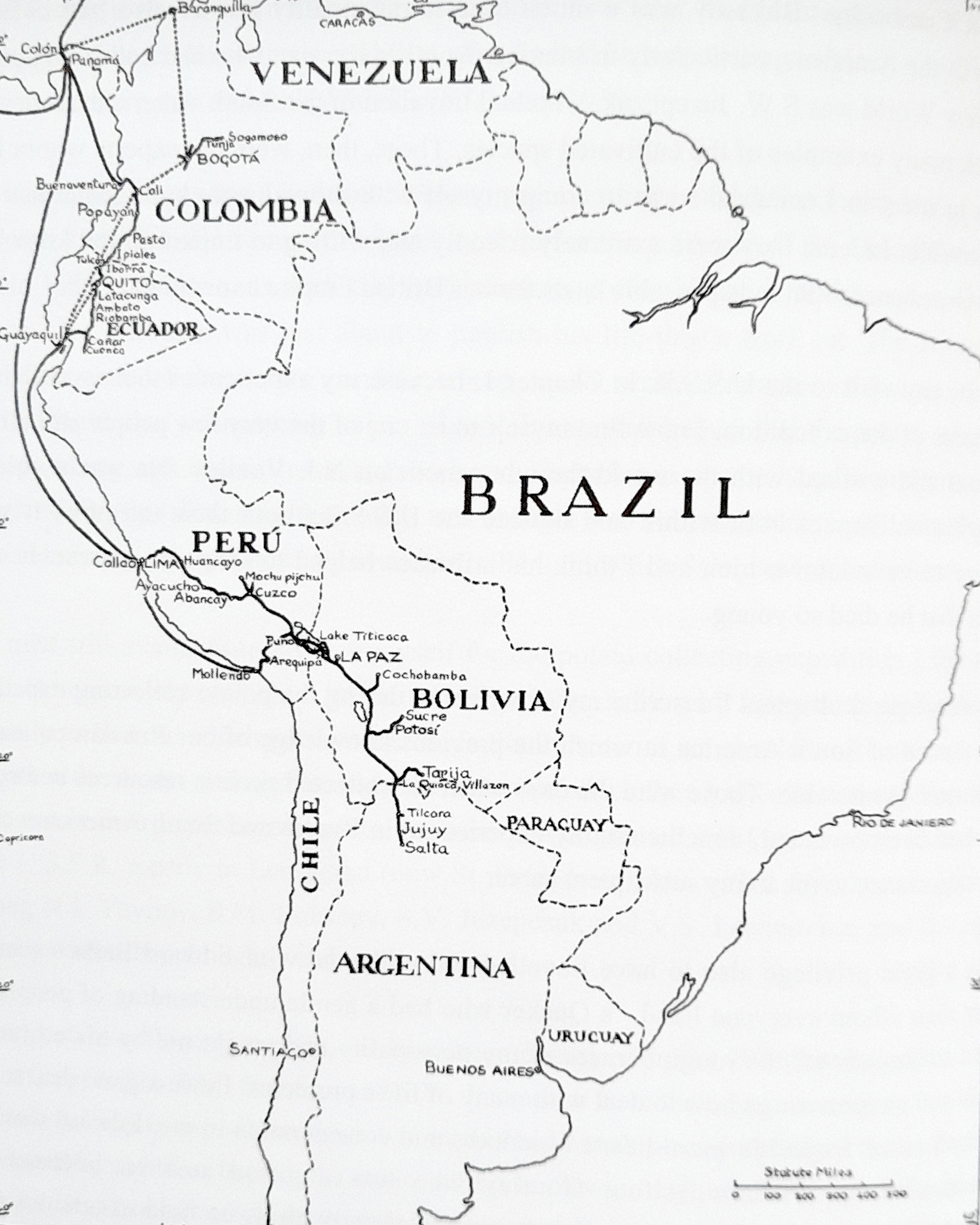

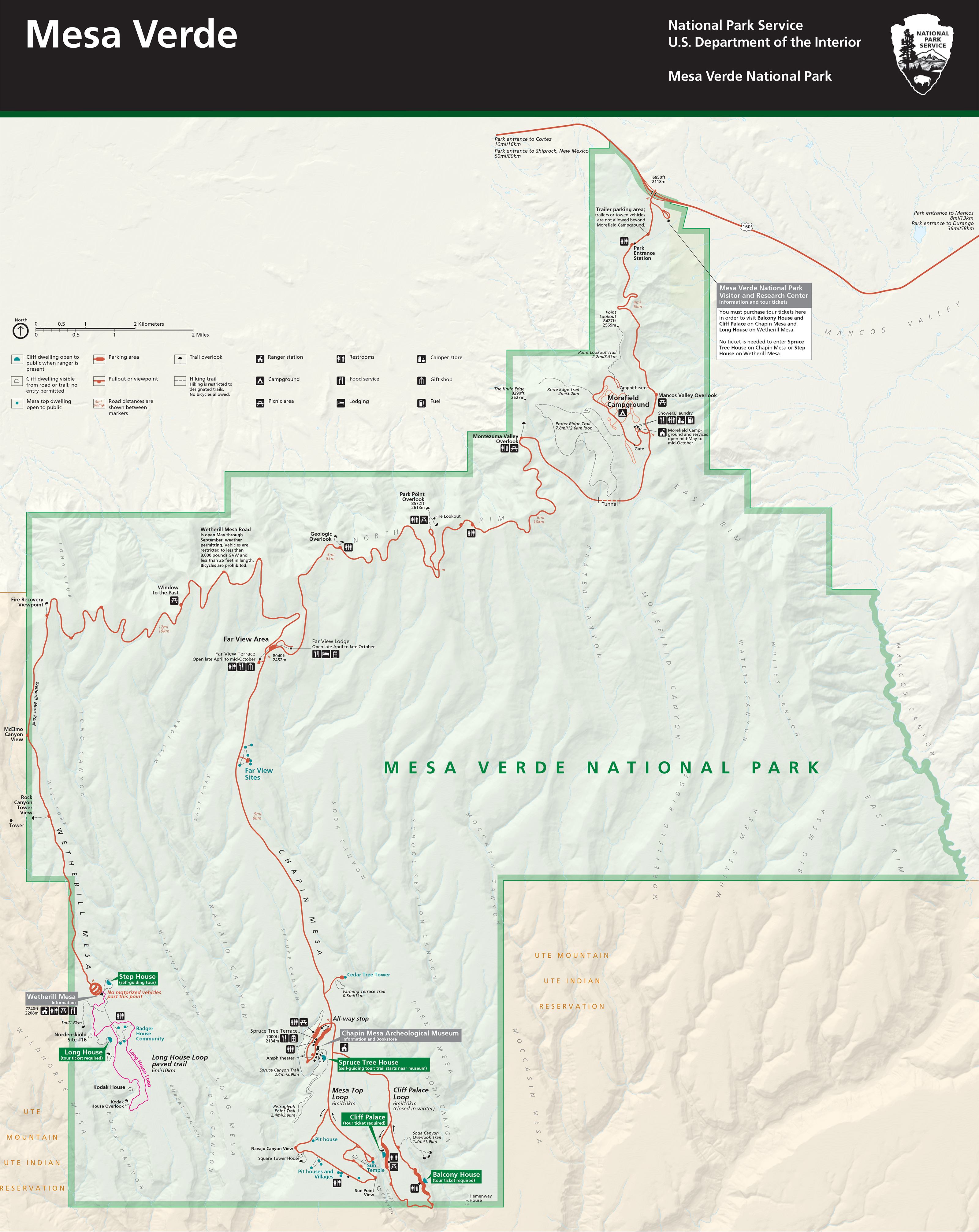

In this map you can see where our excursions have taken us, although our trip to the USA in May-June is not included.

December

The first half of the month was rather quiet. On the 11th, however, we woke to the most glorious sunrise that I think I’ve ever seen. I looked out of my office window just before 8 am, and the sky to the east and south was ablaze.

Later that same day, Steph and I headed off to Seaton Delaval Hall, the National Trust property closest to home—less than 6 miles and about 11 minutes by road. It was our second visit of the year, and we wanted to see what Christmas decorations were displayed. In past years we’ve traveled much further afield but decided to keep closer to home this year, enjoying a welcome cup of coffee in the excellent Brewhouse Café there.

On the 19th we took the Metro into Newcastle city center to have a look around the Christmas market, enjoy a coffee in Grainger Market, and check out the window display, based on A Christmas Carol by Charles Dickens in the Fenwick department store on Northumberland Street.

Here’s a short video about the history of the Fenwick Christmas displays.

Here in the northeast of England, there are many more Christmas light displays on homes roundabout than we ever saw in Bromsgrove over the many years we lived there. Some folks really go overboard, and we had a nice walk around one evening on the 19th.

On Christmas Day, our younger daughter Philippa and her family joined us for Christmas lunch and presents. Phil had done all the preparation and cooking, and we (Steph actually) only had to put the turkey in the oven at the required time before the family arrived.

In general the weather during December has been very disappointing, but we did manage a long walk along the Backworth waggonway on Boxing Day to walk off some of the excess of the previous day.

And we ended the year, on New Year’s Eve as we had started on 1 January, with a walk along Seaton Sluice beach. It was a cracker of a morning, very bright and sunny but bitingly cold. With days of winds from the northeast, there was quite a swell and some of the biggest waves we’ve seen since we started walking there just after moving north in October 2020.

November

This was a quiet month, excursion-wise. November started very mild, with some glorious sunny days, such that we headed north (on the 8th) to one of our favorite locations: Hauxley Wildlife Discovery Centre, just behind the beach at Druridge Bay, south of Amble.

It was a good bird-watching day, with lots of geese and ducks on the water. And a surprise as well. A blackcap (below), normally a summer visitor but a species that is increasingly staying resident in the UK the whole year round.

Then the weather really deteriorated, becoming windy and very wet. By 20 November, the temperature had really fallen and we had two days of frost and snow, quite unusual for November. But at least here in the northeast we were spared the torrential and devastating rains that blighted parts further south, especially in Wales.

Finally, on the last day of the month, and having been ‘trapped’ indoors for several days, the skies cleared and we headed to Seaton Sluice for a bracing walk along the beach.

Oh, and I celebrated my 77th birthday on the 18th, Steph cooking my favorite meal: homemade steak and kidney pie.

October

It has been incredibly mild, with just one slight frost at the end of the month. What’s also remarkable is the number of plants that are still flowering in our garden, including hollyhocks, antirrhinums, and calendulas. Even the odd strawberry plant. And this fine weather has allowed us to take some nice walks locally. Finally the trees are beginning to show some autumn color, like these birches along one of my favorite waggonway walks a couple of days ago.

At the beginning of October (from the 6th) we made a four-day trip to Scotland to visit my sister Margaret who lives west of Dunfermline in Fife, stopping off on the way north at a small fishing community, St Abbs, just north of the border with Scotland. I wrote about that trip in this post.

The harbour at St Abbs.

We visited Stirling Castle (managed by Historic Environment Scotland (HES) – the Scottish equivalent of English Heritage) enjoying the splendour of castle that has stood on a volcanic crag since the 14th century, but became a renaissance palace during the 16th century under James V of Scotland, father of Mary, Queen of Scots.

With my sister Margaret, looking north towards the Wallace Monument and the Ochil Hills from Stirling Castle.

HES has undertaken some impressive refurbishment of the royal palace there. Here is a small selection of some of the sights there.

After lunch, we headed a few miles southwest from Stirling to visit a landscape feature we’ve passed by at high speed on the M9 motorway on a couple of previous occasions. The Kelpies, mythical water horses, 30 m (100 foot) tall horses heads. Very impressive indeed!

On the Wednesday, we headed south to the north Northumberland town of Woolmer, nestling under the Cheviot Hills. We had gift vouchers (from last Christmas) for a tour and whisky tasting at the recently opened (2022) Ad Gefrin distillery and museum, named after an important Anglo-Saxon settlement and royal palace a few miles to the northwest.

Since I wanted to enjoy the whisky tasting, we parked in the town close to the guest house where we spent the night. Next morning – after an excellent full English breakfast – we headed to the site of the Anglo-Saxon settlement, and then crossed over the border again to make a quick visit to ruined Cessford Castle (ancestral home of the Ker family who became the Dukes of Roxburghe), before heading south again and crossing over into Northumberland at Carter Bar.

On 17 October we decided to take the Metro to Tynemouth and walk back to the Metro station at Cullercoats along Long Sands Beach, a little over 2 miles.

Then, just last Monday on the 27th, we headed out the Rising Sun Country Park which is quite close to home, and the reclaimed site of several collieries. What a glorious day, and just right to enjoy a cup of coffee and soaking up the Vitamin D.

Then it was Halloween, and although I don’t have any photos of all the children in their lovely costumes, we did hand out quite a large amount of candy. I guess there was a sugar rush in the houses round-about last night.

September

In some ways, September was a rather quiet month, despite having a week-long break in Somerset from the 5th.

We had booked a cottage in a small community a couple of miles south of Shepton Mallet in central Somerset, with the aim of visiting around a dozen National Trust and English Heritage properties in Somerset and west Wiltshire over the week.

We set out on the Friday morning, heading to Dunham Massey, a large estate owned by the National Trust on the west side of Manchester, and a couple of miles from the Manchester Ship Canal (which we had to cross). Having spent the night in a Premier Inn on the south side of Stoke-on-Trent (not far from where I went to high school in the 1960s), we headed south the next day, stopping off at Dyrham Park, just north of Bath, a property we had visited once before on a day trip from our former home in Worcestershire.

Over the course of the week, our travels took us to three castles, three gardens, one abbey and another now converted to a luxurious manor house, and five impressive mansions.

We also ticked off another location from our bucket list: Cheddar Gorge.

On the 21st (a Sunday), we headed west of Newcastle to the small village of Wylam to view the birthplace cottage of The Father of the Railways, George Stephenson. The cottage, owned by the National Trust, is open only on a few select weekends each year, and as the 200th anniversary of the birth of the railways took place the following weekend (on the 27th), we took advantage of the cottage opening and had booked tickets several months back.

And while the weather continued fine, we enjoyed a glorious walk along the Whitburn coast south of the River Tyne, from Souter Lighthouse towards Sunderland on 26 September. I was surprised to discover that this was our first visit here this year, as it’s one of our favorite places to visit. So after a welcome americano in the National Trust café we set off along the cliffs as far as Whitburn Beach and Finn’s Labyrinth.

In this drone video (from YouTube) you can see the complete walk we took from the Lighthouse to the beach.

August

Hannah and Michael, Callum and Zoë were still with us at the beginning of the month. On the 1st, we had an enjoyable trip north to Druridge Bay, with all the grandchildren, and dogs as well. It was rather overcast, and a fair breeze, but with miles of beach to enjoy, I think everyone had a good time.

Hannah and family returned to the USA on 6 August, and since Philippa and her family had already left for their camping holiday in France, we had the doggies (Noodle and Rex) for the day.

At the site of the former Fenwick Colliery, close to home

We had great walks along Cambois beach on 8 and 12 August, the second time with Rex and Noodle again.

On 13 August, a very hot day, we decided to visit Derwent Walk Country Park, west of Newcastle, and close to the National Trust’s Gibside. Here in the northeast, local government have converted industrial waste sites to country parks and other recreational facilities. The Derwent Walk stretches for miles along the River Derwent, a tributary of the Rive Tyne, joining the latter west of Newcastle.

Never ones to miss out on a freebie, we spent the morning of 15 August picking blackberries close to home, and have enough to keep us in apple and blackberry crumble for the next 12 months!

Since then we have been very quiet, with just one walk along the promenade at Whitley Bay on the 17th, and (almost) daily walks close to home.

I spent many hours in the last week of the month planning visits (and routes) to National Trust and English Heritage properties in Somerset where we’ll spend a week from 6 September.

July

The first half of the month was generally rather quiet. I think we were still in post-USA mode. But with the good weather, I did get out and about on the local waggonways and another of my ‘Metro walks’ – this time from Four Lane Ends to Ilford Road. With the heatwaves that we’ve experienced recently, the vegetation everywhere was looking more like late summer than mid-July.

However, we did make one excursion on 11 July, taking in the birthplaces of father of the railways, George Stephenson (right), in Wylam (which we didn’t tour – it’s open in September and we have tickets then), and Thomas Bewick (renowned wood engraver) at Cherryburn, both owned by the National Trust. Then we stopped by the confluence of the North and South Tyne Rivers near Acomb in Northumberland, before making a second visit to St Oswald’s in Lee church at Heavenfield.

However, we did make one excursion on 11 July, taking in the birthplaces of father of the railways, George Stephenson (right), in Wylam (which we didn’t tour – it’s open in September and we have tickets then), and Thomas Bewick (renowned wood engraver) at Cherryburn, both owned by the National Trust. Then we stopped by the confluence of the North and South Tyne Rivers near Acomb in Northumberland, before making a second visit to St Oswald’s in Lee church at Heavenfield.

On the 17th, we enjoyed an afternoon walk on the beach at Seaton Sluice.

Then, on 26 July, our elder daughter Hannah and her family (husband Michael, and Callum and Zoë) arrived from Minnesota after spending a few days in London prior to their travel north to Newcastle. And we’ve been out and about almost every day since, taking in Seaham in County Durham searching for sea glass (on the 28th), Belsay Hall, Winter’s Gibbet, and Elsdon Castle on the 29th, and the National Trust’s Allen Banks west of Newcastle (that we visited last April) on the 30th.

June

1 June. Not long after breakfast, Hannah drop me off at MSP (less than 10 minutes from her home) so I could collect our hire car for the next four days, for the trip south into north-eastern Iowa.

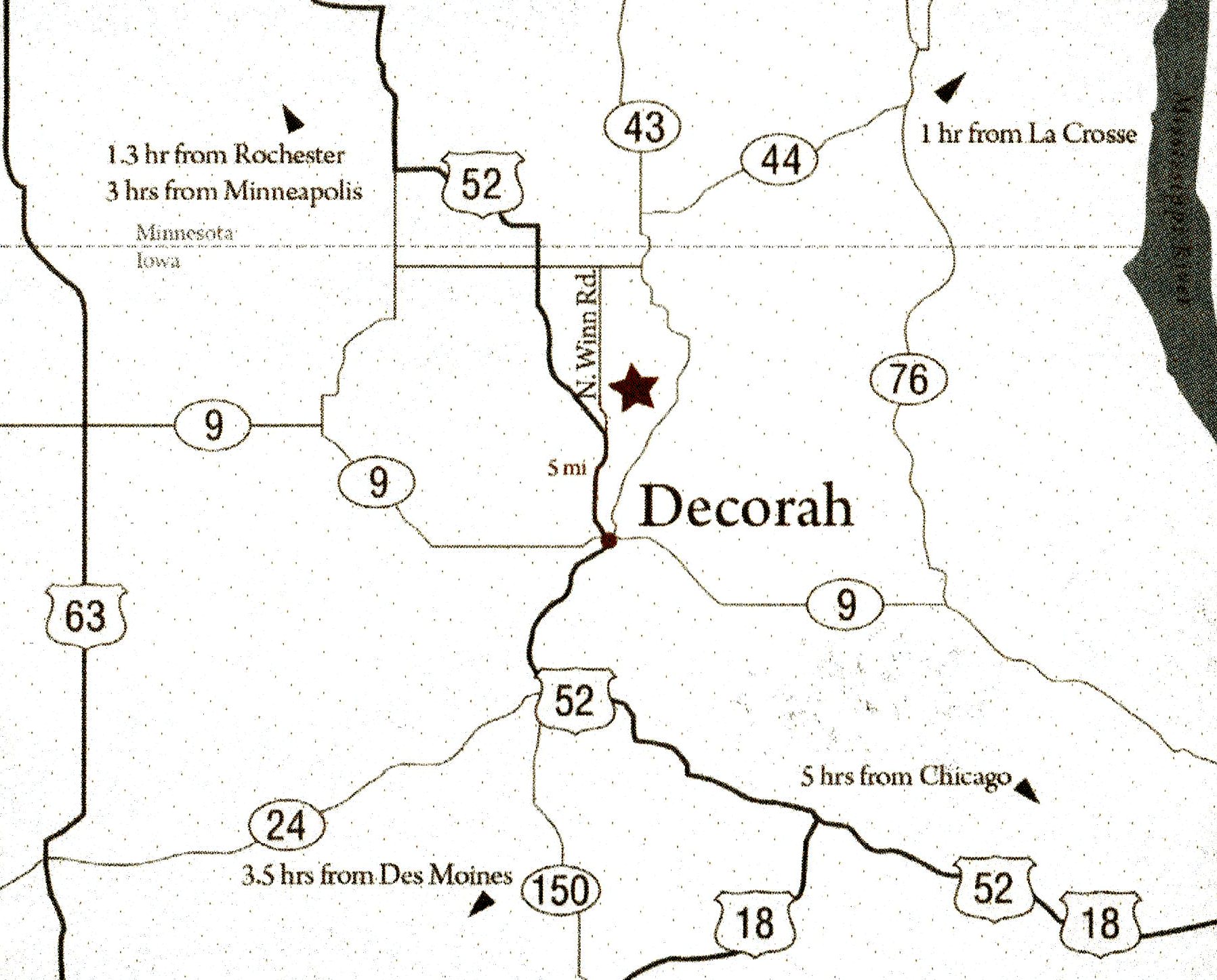

We set off just after 13:30, and took a leisurely drive to Decorah in Iowa where we’d spend the next two nights, for our visit to Seed Savers Exchange the next day.

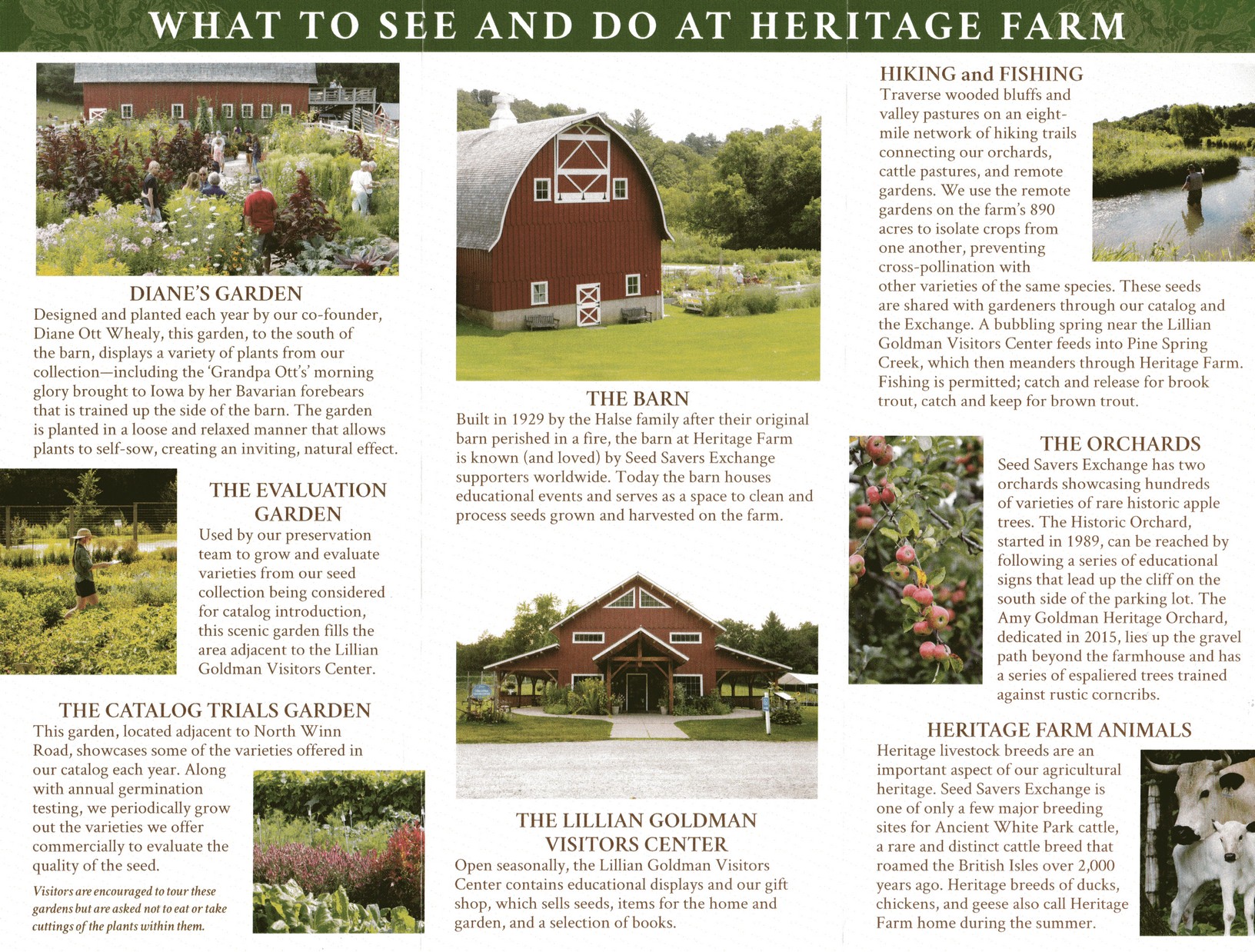

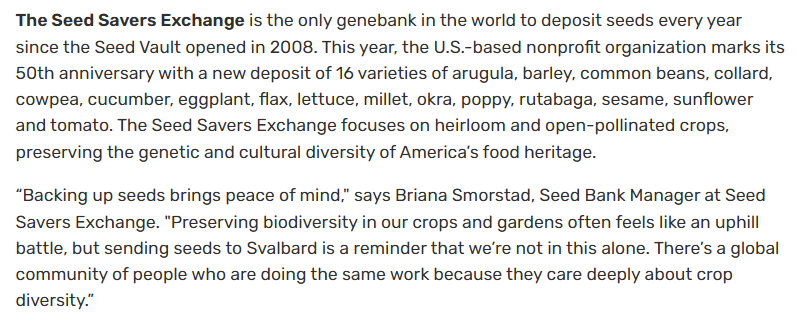

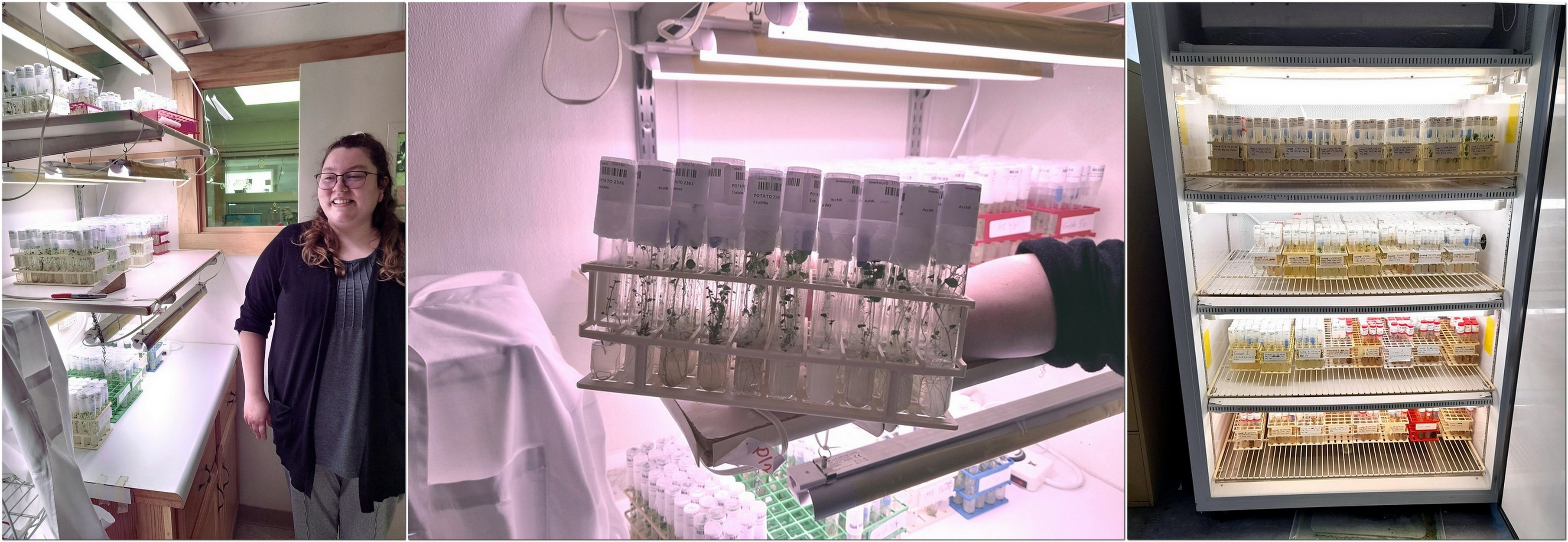

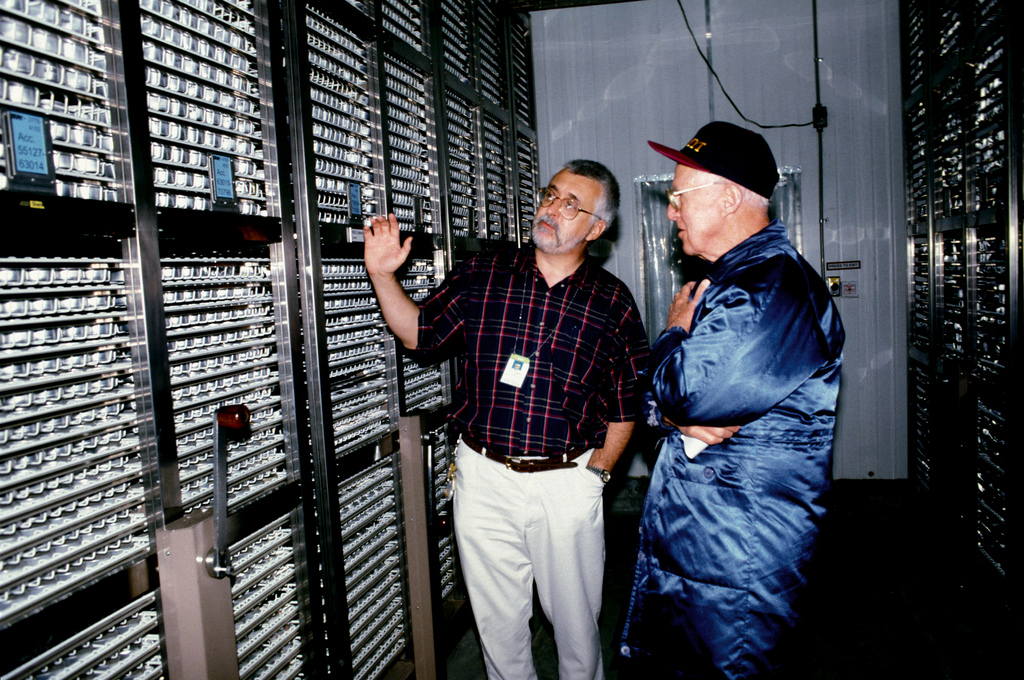

Seed Savers Exchange (SSE) is a wonderful community of gardeners and horticulturalists who collect and preserve heirloom varieties of vegetables, fruits, and some flowers. I had contacted SSE in February about a possible ‘behind-the scenes’ tour of their facilities. And as it turned out we were treated to a six hour visit, which I have described in detail in this post.

We enjoyed looking round Decorah (in Iowa’s part of the Bluff Country). It’s the county seat of Winneshiek County. We were impressed by the various murals that can be seen around the town. The sun was quite hazy that first evening, caused by smoke from Canadian wildfires drifting south.

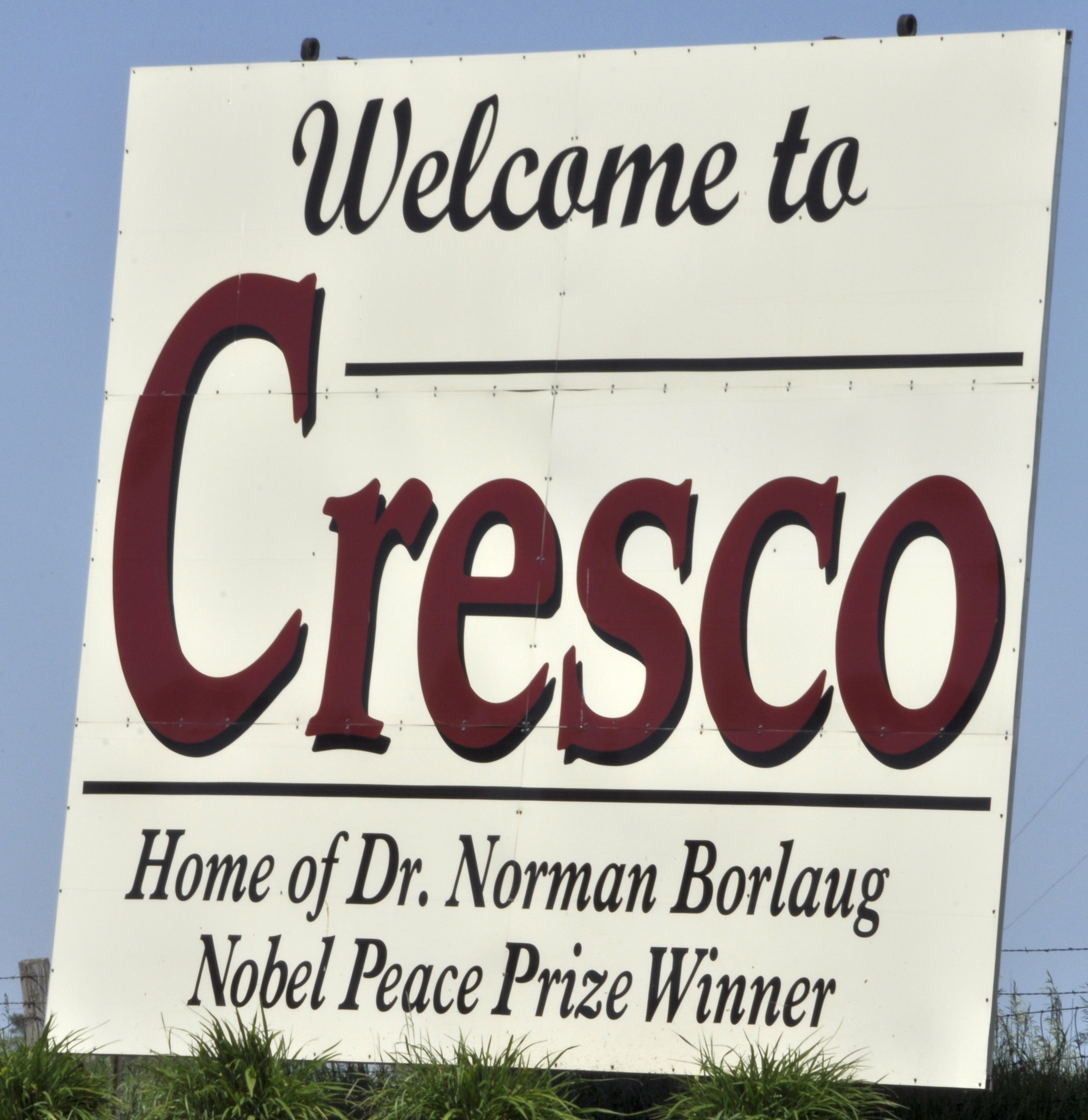

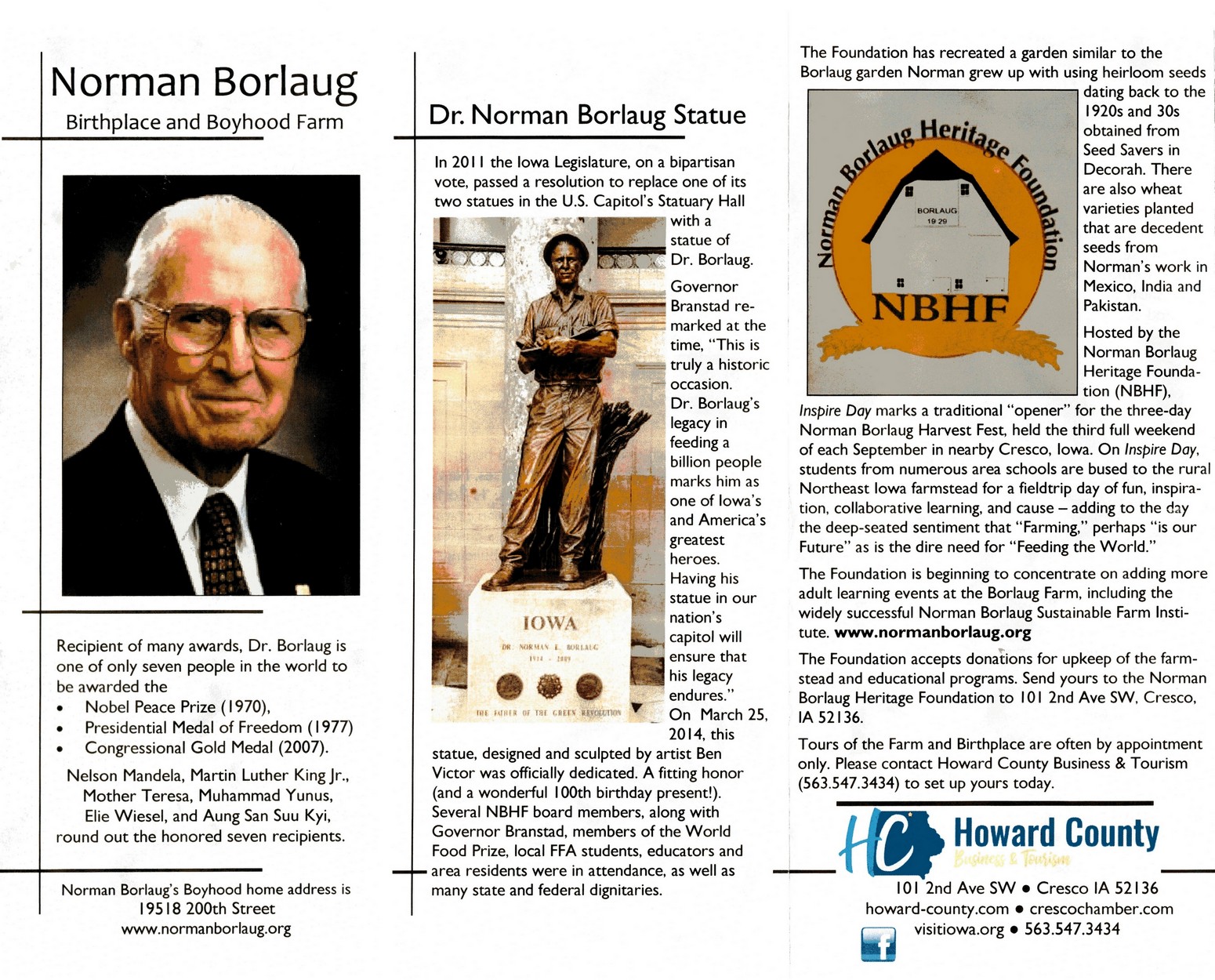

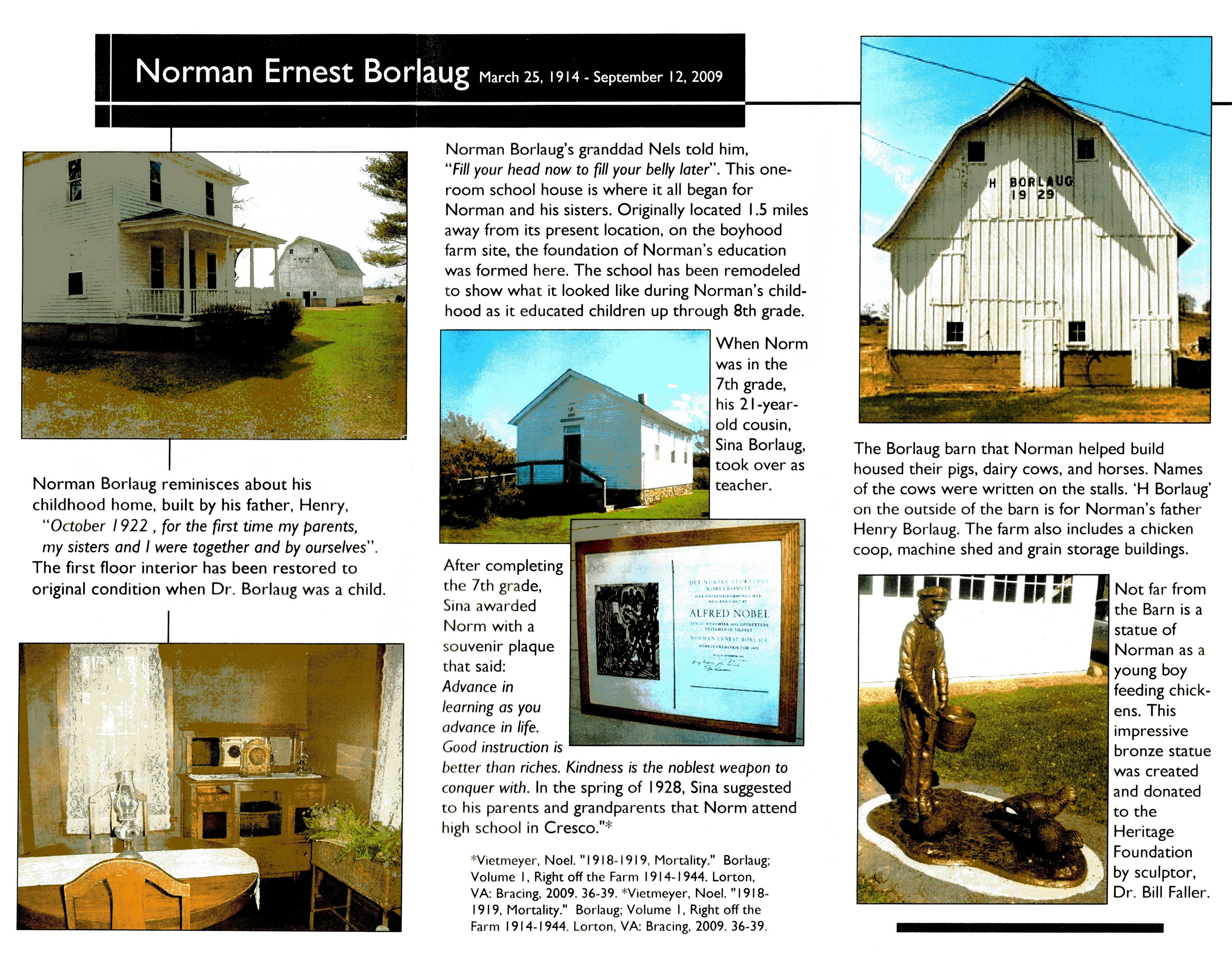

The following day we headed west to Cresco to visit the birthplace and boyhood farms of Dr Norman Borlaug (right), who was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1970 for his research leading to the development of high-yielding varieties of wheat, making several countries self-sufficient in that grain, but also saving millions from the dire prospect of famine. You can read all about Dr Borlaug’s life and career, and our visit to the farm hosted by two members of the Norman Borlaug Heritage Foundation.

The following day we headed west to Cresco to visit the birthplace and boyhood farms of Dr Norman Borlaug (right), who was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1970 for his research leading to the development of high-yielding varieties of wheat, making several countries self-sufficient in that grain, but also saving millions from the dire prospect of famine. You can read all about Dr Borlaug’s life and career, and our visit to the farm hosted by two members of the Norman Borlaug Heritage Foundation.

One the last day, as we headed back to the Twin Cities, we stopped off at Nerstrand Big Woods State Park in Minnesota (about 60 miles south of the TC), and enjoyed a peaceful 3 mile walk through the park, visiting the Hidden Falls, and having a picnic lunch before hitting the road again.

After our return to St Paul, we spent the rest of our time there chilling out, walking along the Mississippi, dining out with the family. And we did enjoy an afternoon of mini-golf on the roof of Minneapolis’ Walker Art Center, and looking at some of the sculptures in the Garden. It was so hot!

Then it was time to pack up and fly back to the UK on 17 June. Looking back on our 3 weeks plus in the USA, we had a great time, despite all the dire warnings about what is happening there right now. We had no issues at immigration, nor on departure. Everyone we met was friendly, but perhaps that’s just the Mid-West culture. But it’s so sad to hear how the Trump administration is dismantling the very fabric of democracy, and it’s scary how the Supreme Court is supporting him.

We arrived back the following day to a heat wave, and decided to barbecue the next. Since then we’ve been getting over jet-lag, but have managed a coupe of short excursions.

On the 25th we took one of our favorite walks from Whitley Bay to St Mary’s Lighthouse. It’s always nice to walk beside the sea.

Then, on the last day of the month, and one of the hottest of the year, we once again visited the Penshaw Monument (about 11 miles south of where we live) and Herrington Country Park.

May

What a busy month May has been. With good weather over several days during the first half of the month, we managed three excursions, before departing to Minnesota for almost a month on 21 May, flying from Newcastle International Airport (NCL) to Minneapolis-St Paul (MSP) via Schipol (AMS).

Om 3 May, I continued my exploration of the Tyne and Wear Metro, walking between Four Lane Ends and Chillingham Road ( just under 4 miles), taking the train from Northumberland Park to Four Lane Ends, then from Chillingham Road all the way east to Tynemouth before turning west again to arrive back at Northumberland Park. On 13 May, I explored the short distance between Four Lane Ends to Benton, before taking the metro back home.

On a couple of walks on nearby fields at the beginning of the month, I was lucky to observe kestrels, yellowhammers, and lapwings, all putting on impressive flight or vocal displays.

On 9 May, we returned to Kielder Forest in the west of Northumberland, making the Forest Drive east to west this time. What a beautiful part of the county.

We had never visited our local National Trust property Seaton Delaval Hall (just under 6 miles from home) in the Spring. But finally made it on 16 May.

Then on 17 May, we enjoyed a fine barbecue.

Our trip to Minnesota began at 06:30 when our taxi picked us up for the short ride to Newcastle airport. The airport was quiet and we were soon checked through and had a couple of hours to wait for our 09:30 flight on KLM to AMS. I had been concerned about the relative short connect ion time in AMS (just 1¼ hours). But we arrived on time, and our Delta flight to MSP departed from an E gate quite to close to where we had arrived on the D pier.

The Delta flight was not full, and we had a very comfortable flight, arriving on time in MSP at around 15:00. We were through immigration and baggage collection and out of the airport in around 20 minutes. Hannah was there to pick us up. And although jet-lagged, we did manage to stay awake to hear Callum (our eldest grandson) sing in a school concert that evening.

Apart from a short trip to Iowa from the beginning of June (which I will describe in next month’s update) we had no road trip plans during this year’s visit to the USA. So we stayed mostly around the neighbourhood where Hannah and Michael live, enjoying walks, chilling out with their two dogs, Bo and Gizmo, reading, and sampling many of the local beers.

It was interesting to see how much the Highland Bridge development and parks had progressed since 2024. This is the site of a former (and huge) Ford motor assembly plant. The City of St Paul has been very imaginative in its planning of the development (condos, town houses, commercial properties, healthcare, and landscaping – it’s incredible how much wildlife has already taken up residence).

We enjoyed a couple of hours exploring Excelsior and the shore of Lake Minnetonka west of the Twin Cities, while Hannah had brunch with a former work colleague. Lake Minnetonka is now one large lake formed by the merging into a single body of water of numerous kettle lakes after the last glaciation.

On Memorial Day (26 May) we took a walk from the Minneapolis side of the Mississippi back to Hannah’s stopping off the Longfellow Gardens and Minnehaha Park and Falls. We encountered a group of (mainly) old folks protesting against Trump. Well done!

Michael had been smoking several racks of pork ribs for about six hours, and his father Paul and partner Marsha joined us for a delightful evening meal on the patio.

On 30 May we made our annual ‘pilgrimage’ to Como Park in St Paul and the Marjorie McNeely Conservatory (where Hannah and Michael were married in 2006) to see what floral display the gardeners had designed for 2025. The visit to Como was completed with a stroll around the Japanese Garden, and to watch the glorious carousel nearby.

On the last day of the month we prepared for our trip south to Iowa the next day.

April

It has been one of the driest Aprils on record, so we’ve had lots of opportunities of getting out and about.

The month started, right on the 1st, with Steph and I receiving our Covid-19 Spring booster vaccinations. One of the advantages of being over 75 – we get offered these vaccinations twice a year. We believe in science, not the mad ravings of RFK, Jr!

The month started, right on the 1st, with Steph and I receiving our Covid-19 Spring booster vaccinations. One of the advantages of being over 75 – we get offered these vaccinations twice a year. We believe in science, not the mad ravings of RFK, Jr!

The next day, we headed 75 miles south to Fountains Abbey and Studley Royal Water Gardens just beyond the small cathedral city of Ripon in North Yorkshire. We’ve been there twice before, in July 2013 and again at the end of March 2014. On both occasions it was heavily overcast and rather cold. Not so on this latest visit. We enjoyed a walk of almost 5 miles in the warm sunshine. The ruins of the abbey looked magnificent, likewise the water gardens.

Less than a week later, we headed south once again, this time to Barnard Castle to explore the 11th century castle and then on to the ruins of Egglestone Abbey, just a couple of miles south of the town. Both owned by English Heritage.

We then came home via the road from Teesdale to Weardale.

I made another of my Metro walks the following day, from West Monkseaton to Monkseaton, and rode one of the new Stadler consists for the first time.

On the 11th, Steph and I headed to the coast to take a look at the newly-renovated St Mary’s Lighthouse. The last time we were there it was high tide so couldn’t cross to the island. As usual, there was a good number of grey seals basking on the rocks.

On the 11th, Steph and I headed to the coast to take a look at the newly-renovated St Mary’s Lighthouse. The last time we were there it was high tide so couldn’t cross to the island. As usual, there was a good number of grey seals basking on the rocks.

It wasn’t until the 22nd that we had another excursion, a return visit to Hauxley Wildlife Discovery Centre, where we saw many of the birds that were highlighted on the centre’s reporting board. Including a rare ruddy shelduck, probably an escape or a migrant that had lost its way.

Finally, on the last day of the month, and 15 years to the day since I retired from IRRI in the Philippines, we made a second visit to the National Trust’s Allen Banks and Staward Gorge, about 6 miles west of Hexham. Another glorious day, and we enjoyed a 4 mile return walk along the banks of the River Allen to Plankey Mill from the car park. We’d visited once before at the end of October 2022.

This recent walk was particularly pleasant as the woodlands were waking up in the Spring sunshine.

Internationally, this month saw the death of Pope Francis, and the dramatic election win for Mark Carney and the Liberal Party in Canada, overturning a predicted drubbing from the nation’s right wing Conservative Party. Donald Trump and his henchman continue to embarrass themselves, the USA, and democracy.

March

This has been a walking month, but with a difference. Having walked the waggonways and fields close to home over the past four years, I decided it was time to explore further afield. So, on several occasions, I have taken to the Metro and walked back home as I did at the beginning of the month from Palmersville (the next station west from our nearest at Northumberland Park) or traveling to other stations and taking a walk from there.

On the 9th, Steph and I headed to Cullercoats, on the coast to walk back to Whitley Bay. Ethereal. There was a light fog rolling off the North Sea which added atmosphere to our walk. By the time we reached the Metro in Whitley Bay, the fog had lifted.

On the 20th, we headed west to Bolam Lake Country Park, making two full circuits of the lake by slightly different routes, enjoying a picnic, before taking a look at the nearby Anglo-Saxon Church of St Andrew’s.

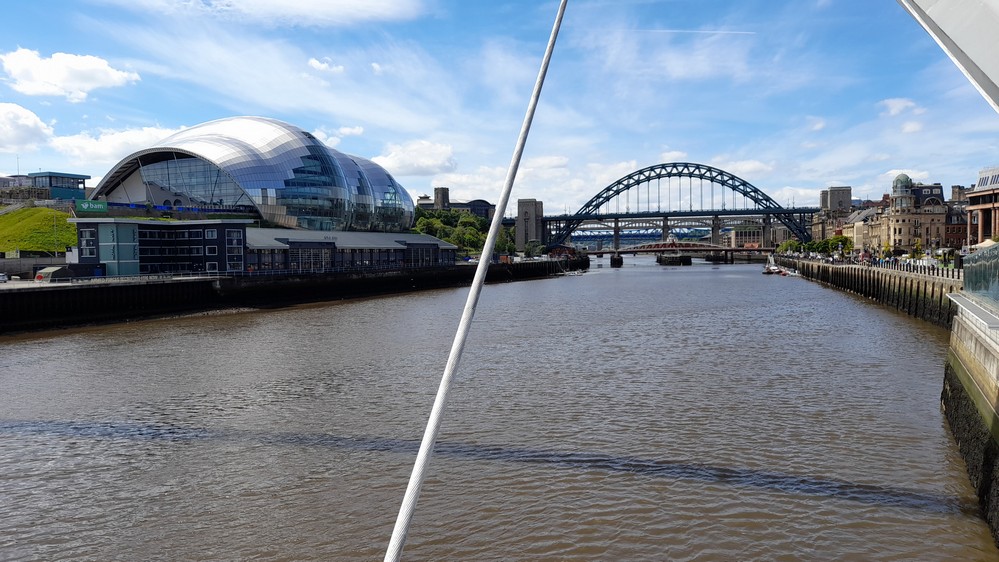

We have explored the center of Newcastle on just a few occasions. However, on 24 March, I took the Metro to West Jesmond, and walked across the city center to St James’ Park (home of Newcastle United), stopping off near Northumbria University for a coffee with my elder daughter Philippa who is an Associate professor there.

Last Friday, 28 March Steph and I took the Metro to Ilford Road, and walked the length of Jesmond Dene, covering almost 5 miles by the time we returned home.

Jesmond Dene is a public park, occupying the steep valley of the River Ouseburn. It was created by William, Lord Armstrong (engineer and industrialist owner of Cragside in Rothbury, now in the hands of the National Trust) in the 1860s, and he gave the park to the people of Newcastle in 1883.

Although showery at times, it was a thoroughly enjoyable walk through the Dene, lots of birdlife (some of which I hadn’t seen for several years such as jays).

However, at the beginning of the month we visited the National Glass Centre in Sunderland for the second time, and took advantage of the visit to explore the nearby St Peter’s Church (with its Saxon tower) which had been closed when we traveled there in November 2022.

Here are some of the studio pieces on display in the Glass Zoo and Menagerie exhibitions.

St Peter’s is one half of the twin monasteries established by Benedict Biscop in the 7th century. The other half is at St Paul’s, Jarrow that we visited in August 2023.

Internationally, I guess the big story has been the powerful earthquake on 28 March in Myanmar, with its epicenter close to Mandalay. Even 1000 km south in Bangkok the effects of the earthquake were devastating. What has been particularly awful about this tragedy has been the request by the Myanmar military junta for international aid while continuing to bomb so-called rebels throughout the country. No humanity!

I am unable to fathom why Israel continues to bomb civilian targets in Gaza, killing recently more than 400 people including many women and children. And why the Israeli government tacitly permits settlers to attack Palestinian families on the West Bank. Meanwhile, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu joined soldiers of the Israeli Defence Force for a meal in a Palestinian apartment which they had occupied. Obscene.

And don’t get me started on what the Trump Administration has been up to, almost on a daily basis, during March.

February

It’s been a rather quiet month on the home front. Why? The weather has been so foul – cold, wet, and overcast and certainly not the weather (mostly) for excursions. Apart from the 6th, when there was hardly a cloud in the sky so we headed off to National Trust Gibside, and enjoyed a 4 mile walk through the estate and along the River Derwent. Hoping to see a lot of birdlife, it was rather a disappointment apart from a solitary dipper feeding along the river, and a stately heron sunning itself a little further along.

On the 26th, our two grandsons Elvis and Felix spent the day with us during their half-term break. We originally had plans for a trip into the wilds of Northumberland, but the weather deteriorated, Elvis had hurt his ankle at a Parkour class the previous week, so all we could manage was a short hobble around the nearby lake.

But the following day, Spring arrived. I even resurrected my summer straw hat from the recesses of my wardrobe.

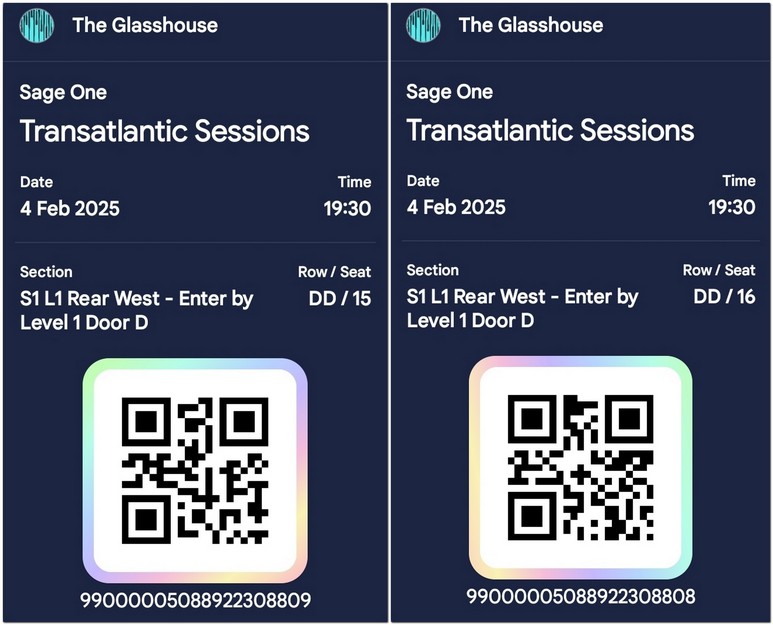

The highlight of the month however was the Transatlantic Sessions concert we attended at The Glasshouse International Centre for Music in Gateshead on 4 February. What an evening! Read all about it by clicking on the box below (and the other red boxes).

I commented about Donald Trump twice during the month. I’d promised myself many weeks ago, even before his inauguration of 20 January, that I would avoid writing anything. I couldn’t help myself.

So on 17 February I published this:

Then, Trump reposted this offensive AI-generated video about Gaza on his Truth Social at the end of the month:

Trump was publicly fact-checked by President Macron of France and prime Minister Sir Keir Starmer of the UK.

On the 28th, I wrote this:

And just when you didn’t think he could sink any lower, Donald came up trumps later that same day, and he and his VP disgraced the Office of the President of the United States in the behaviour towards and treatment of President Volodymyr Zelenskyy of Ukraine in the Oval Office. I’ll just leave this video and let you make your own minds up. I’m appalled.

And this comes on top of Trump being invited to the UK this year or next for an unprecedented second State Visit. Although not a monarchist, I feel sorry for the King that he’s been put in this invidious position, welcoming a convicted felon and sexual abuser once more to the UK.

I also updated these two posts:

January

The weather was quite mixed during this month, with Storm Éowyn (see below) arriving on the 24th, and causing widespread disruption. Having slipped and broken my leg (back in 2016) when it was icy, I rarely venture out these days when there are similar conditions. But we managed a great walk at Cambois beach on 10 January, a rather disappointing bird-watching visit to Hauxley Wildlife Discovery Centre on the 15th, and last Thursday (30th), on a beautiful but sharp sunny day, we completed the River Walk at National Trust Wallington in Northumberland.

Cambois beach

Hauxley Wildlife Discovery Centre

Wallington

Here are some other news items:

- 31 January: Donald Trump has been President for just eleven days, and already it feels like a lifetime.

- 31 January: a Medevac Learjet 55 crashes into a Philadelphia suburb just after take-off from Northeast Philadelphia Airport, killing all on board. This was the second fatal crash in two days in the USA.

30 January: Singer and actress, and 60s icon, Marianne Faithfull (right) died, aged 78.

30 January: Singer and actress, and 60s icon, Marianne Faithfull (right) died, aged 78.- 29 January: American Airlines 5342 (from Wichita, Kansas) collided with an army helicopter as it was coming into land at Washington Ronald Reagan National Airport (DCA), and plunged into the Potomac River, killing all 64 passengers and crew, and three soldiers in the helicopter. Donald Trump ‘speculates’ – because he has ‘common sense’ – about the causes of the accident and, to the outrage of many, blames the accident on the Obama and Biden administrations, and diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) policies.

- 24 January: Storm Éowyn hit the UK and Ireland with winds in excess of 100 mph.

- 20 January: the Orange moron, Donald J Trump was inaugurated as the 47th President of the United States, and immediately disgraced himself in his speech.

- 15 January: Gaza ceasefire agreed between Hamas and Israel, coming into force on the 19th when the first Israeli hostages and Palestinian prisoners exchanged.

9 January: state funeral, in Washington DC for Jimmy Carter, the 39th President of the United States. A president with an impressive legacy.

9 January: state funeral, in Washington DC for Jimmy Carter, the 39th President of the United States. A president with an impressive legacy.- 7 January: catastrophic wildfires devastate huge areas of Los Angeles, leaving thousands homeless.

- 7 January: 7.1 earthquake hits holy Shigatse city in Tibet, with as many as 400 people killed, and many more injured.

- 6 January: Vice President Kamala Harris certifies the 2024 US presidential election results. Justin Trudeau resigns as Prime Minister of Canada. Widespread flooding in the UK.

I wrote these four posts:

New Year’s Day 2025

After a stormy few days, with expectations of worse to come today, we actually woke to a bright, fine morning, blue skies and only a moderate breeze.

Having been confined to indoors for the past couple of days, we decided to head off to Whitley Bay and take a stroll along the promenade, and check whether the sea was still churning after all the recent weather. As the car park was full, we then drove north by a couple of miles to Seaton Sluice, and enjoyed a short (1.07 miles) walk along the beach, collecting small pebbles and sea glass on the way. The temperature was around 7°C but felt much colder in the brisk breeze.

And, at

And, at

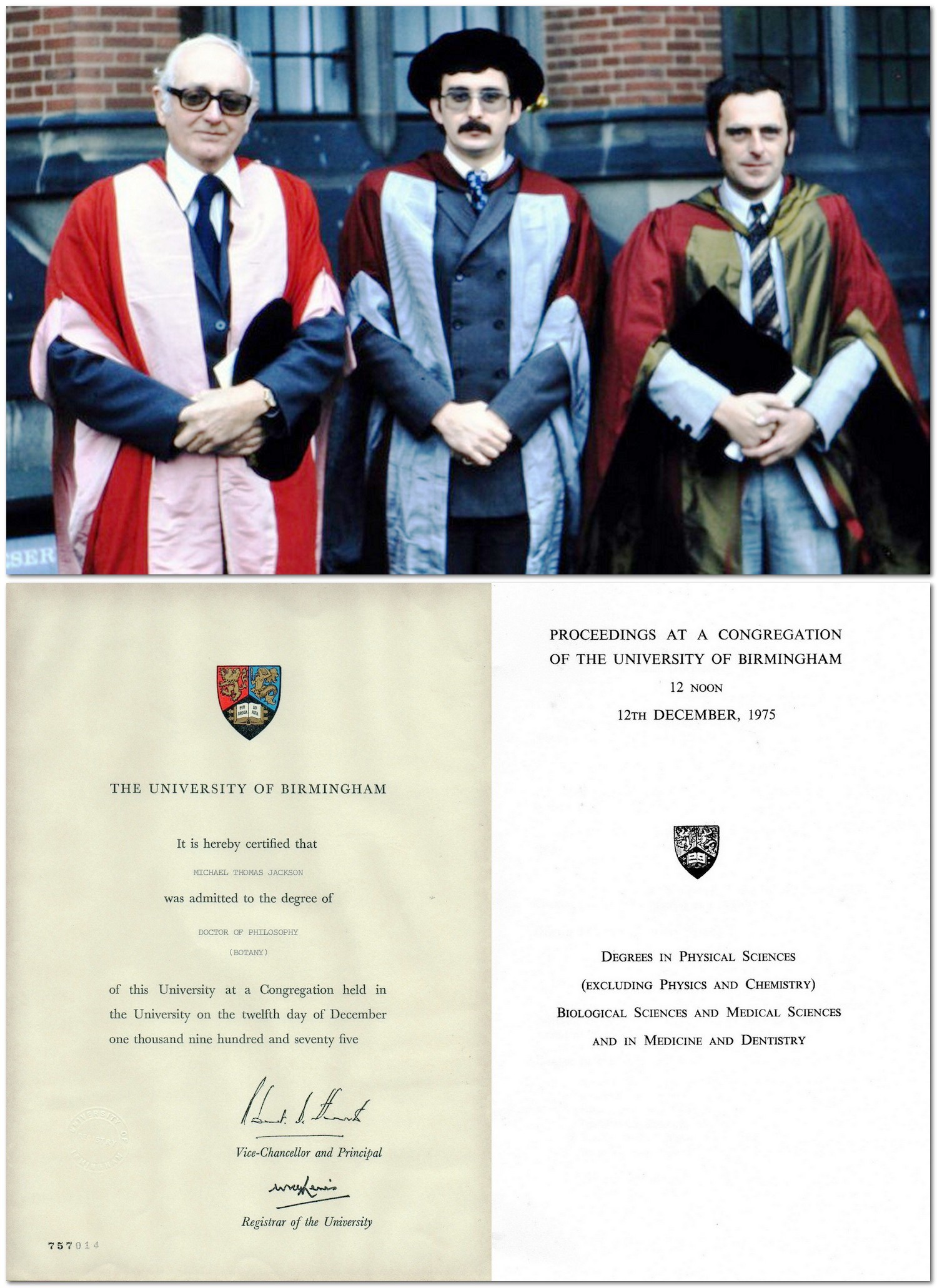

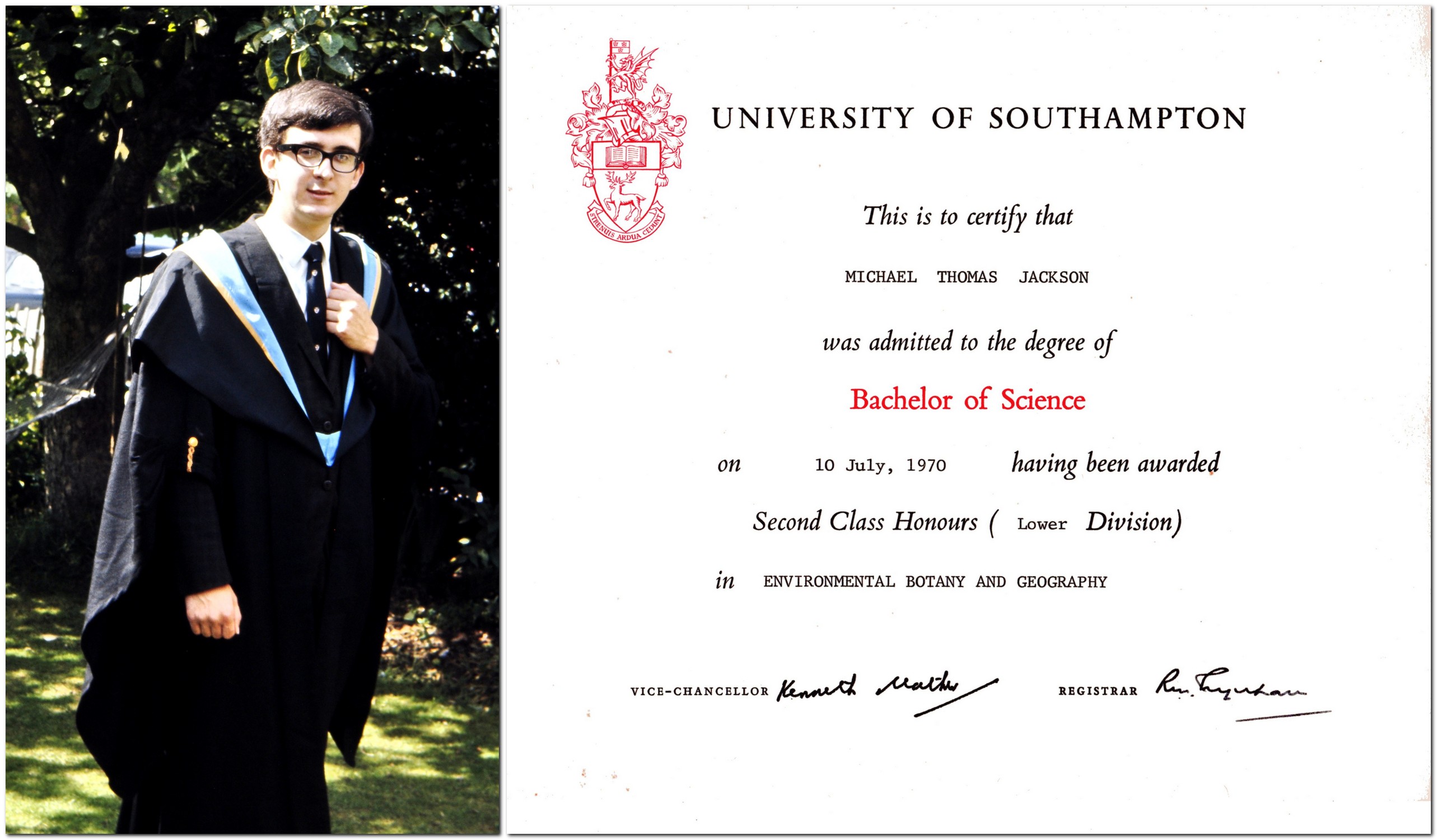

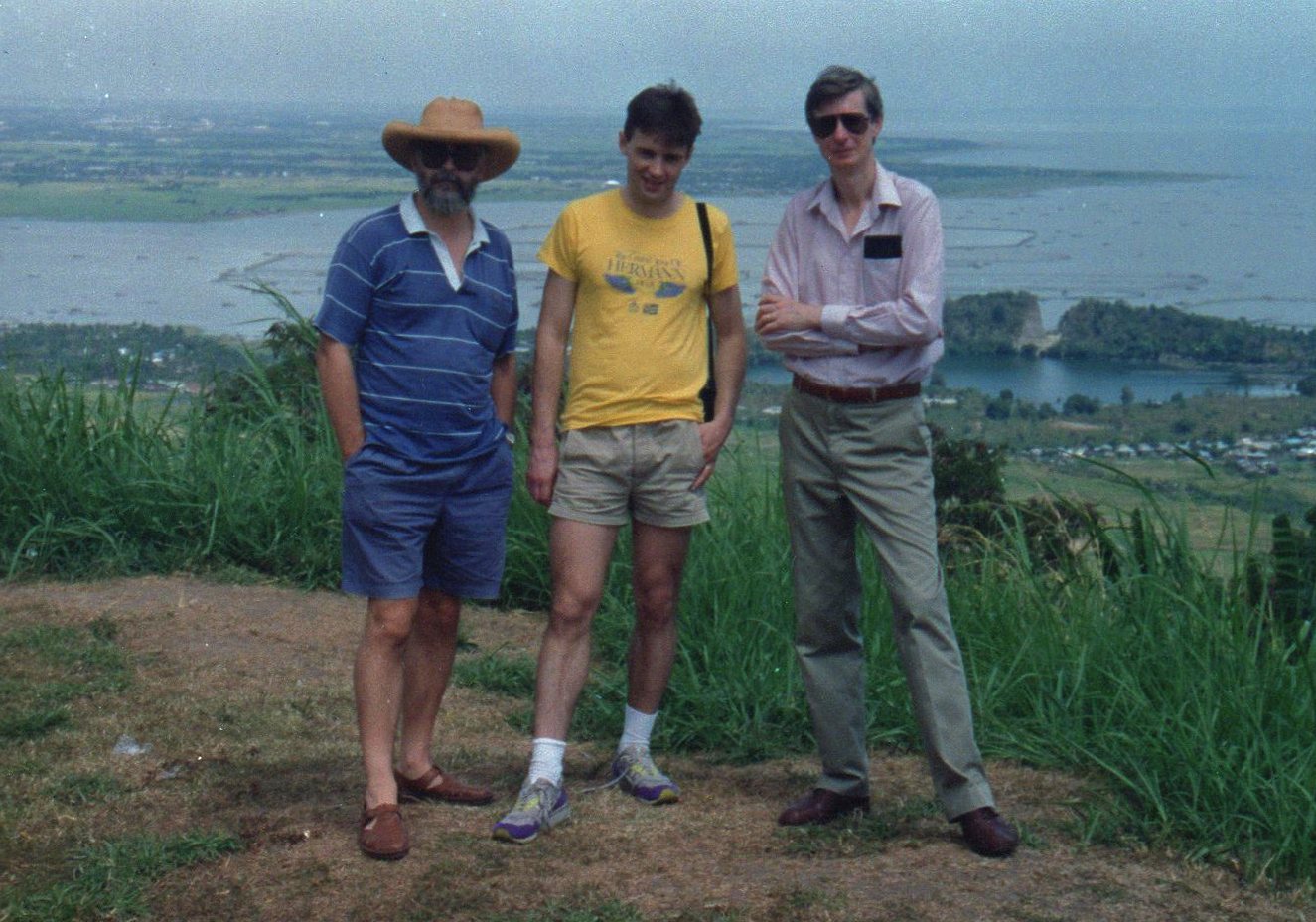

returned to Birmingham from an expedition to collect wild potatoes in Bolivia. He told me about a one-year vacancy from September that same year at the

returned to Birmingham from an expedition to collect wild potatoes in Bolivia. He told me about a one-year vacancy from September that same year at the

His younger colleague,

His younger colleague,

Almost two weeks ago, I received the sad news from Liz’s husband, John Harvey, that she had passed away on 30 August. She was 76.

Almost two weeks ago, I received the sad news from Liz’s husband, John Harvey, that she had passed away on 30 August. She was 76. And today, 27 September 2025, is the 200th anniversary of the opening of the

And today, 27 September 2025, is the 200th anniversary of the opening of the  For this, and other inventions and innovations such as surveying lines, the standard gauge (at 4 feet 8½ inches) that was more or less adopted worldwide, and design of steam locos, George Stephenson is often referred to as the Father of the Railways, and rightly so. Although perhaps that’s an accolade that should be shared with son Robert (right).

For this, and other inventions and innovations such as surveying lines, the standard gauge (at 4 feet 8½ inches) that was more or less adopted worldwide, and design of steam locos, George Stephenson is often referred to as the Father of the Railways, and rightly so. Although perhaps that’s an accolade that should be shared with son Robert (right).

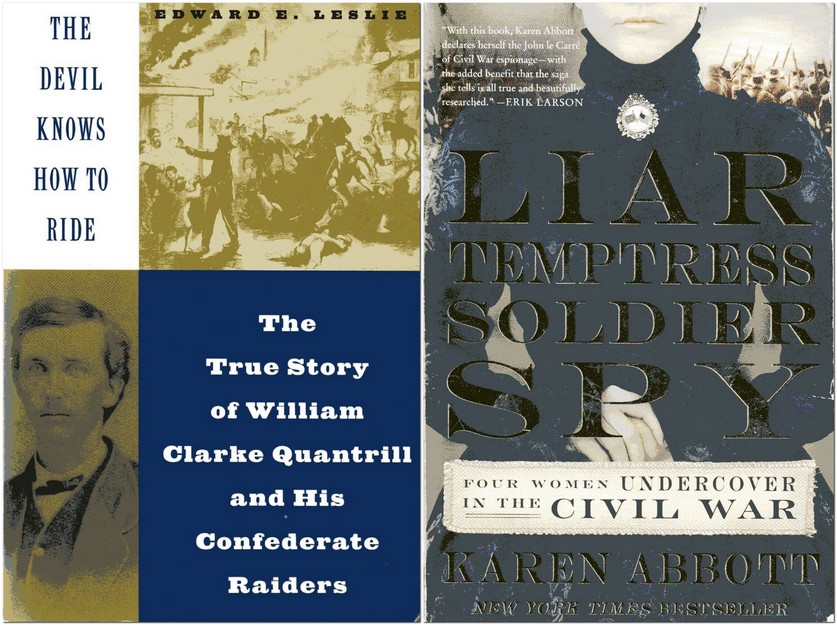

And it was one of these, April 1865: The Month that Saved America (first published in 2001) by acclaimed author and historian

And it was one of these, April 1865: The Month that Saved America (first published in 2001) by acclaimed author and historian

It was the beginning of an international effort to enhance agricultural productivity that endures to this day through the centers of the

It was the beginning of an international effort to enhance agricultural productivity that endures to this day through the centers of the

His is one of two Iowa statues in the US Capitol’s Statuary Hall, unveiled in 2014 and replacing one of the state’s existing statues. It was sculpted by

His is one of two Iowa statues in the US Capitol’s Statuary Hall, unveiled in 2014 and replacing one of the state’s existing statues. It was sculpted by

Norman’s grandparents, Emma and Nels (and others of the Borlaug clan) settled in the Cresco area. They had three sons: Oscar, Henry (Norman’s father, second from left), and Ned.

Norman’s grandparents, Emma and Nels (and others of the Borlaug clan) settled in the Cresco area. They had three sons: Oscar, Henry (Norman’s father, second from left), and Ned.

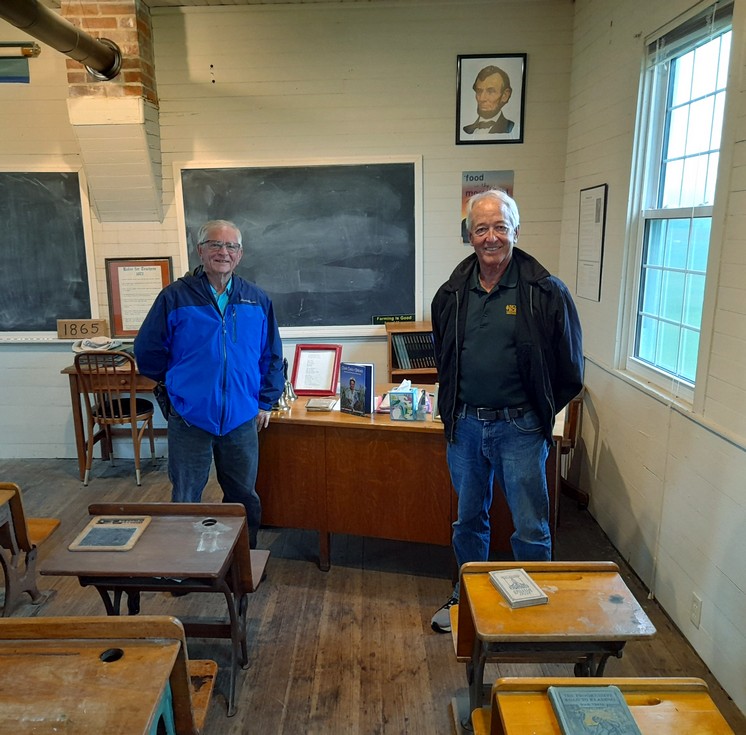

At that time, most pupils reaching Grade 8 would leave full-time education and return to working on the family farm. But Norman’s teacher at the time, his cousin Sina Borlaug (right), encouraged both parents and grandparents to permit Norman to attend high school in Cresco. Which he did, boarding with a family there Monday to Friday, returning home each weekend to take on his fair share of the farm chores.

At that time, most pupils reaching Grade 8 would leave full-time education and return to working on the family farm. But Norman’s teacher at the time, his cousin Sina Borlaug (right), encouraged both parents and grandparents to permit Norman to attend high school in Cresco. Which he did, boarding with a family there Monday to Friday, returning home each weekend to take on his fair share of the farm chores.

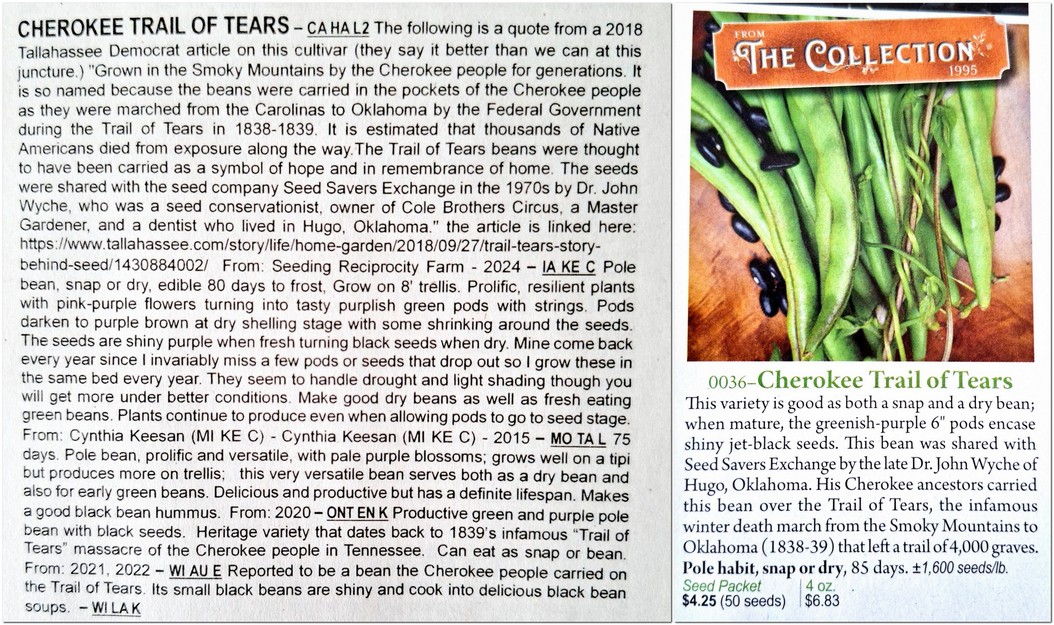

Varieties such as these (of the many thousands in the Exchange network and collection):

Varieties such as these (of the many thousands in the Exchange network and collection):

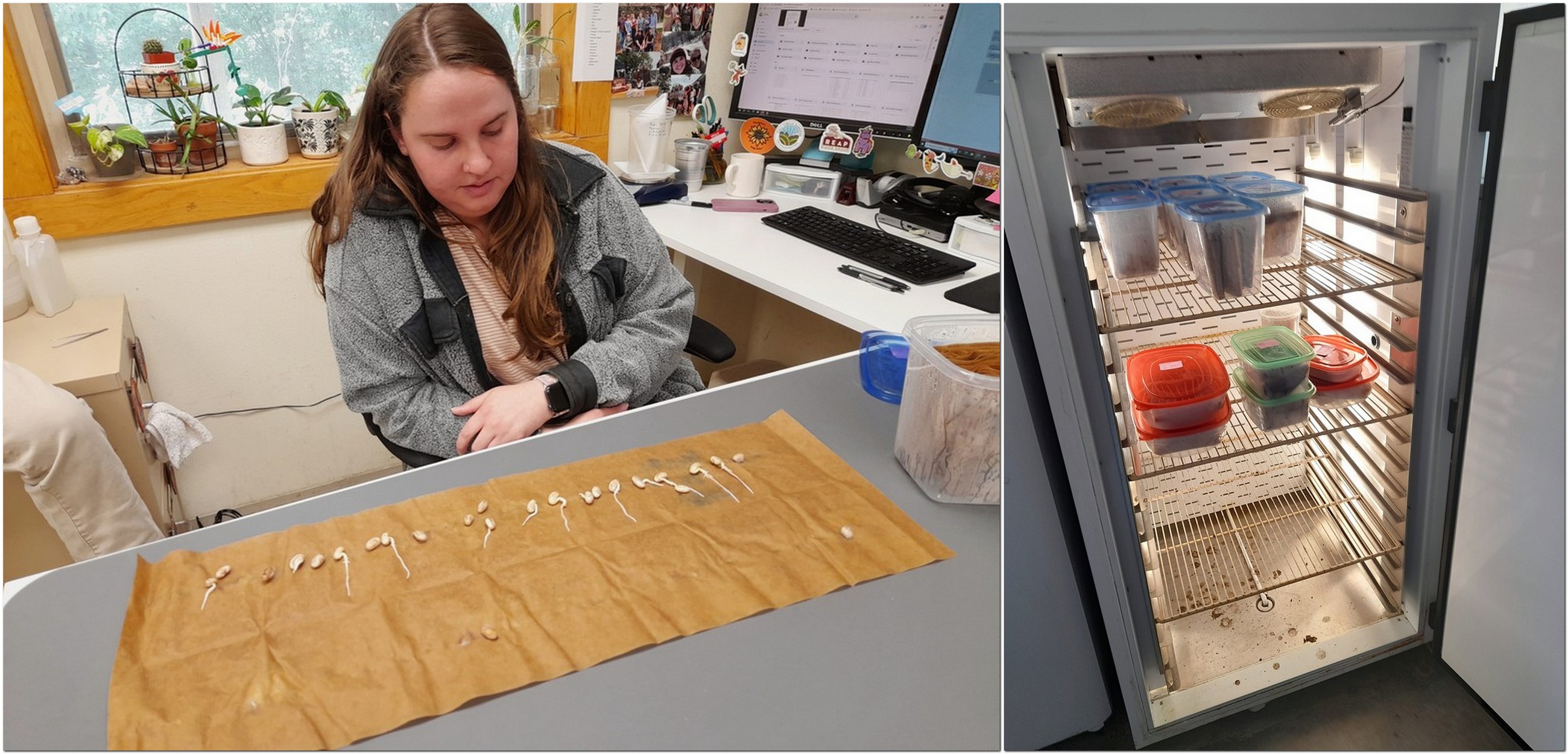

A visit to Seed Savers Exchange was first mooted in May 2024, but having just made a long road trip across Utah and Colorado, I really didn’t want to get behind the wheel again. However, we had no epic road trip plans this year, so I decided to contact Executive Director,

A visit to Seed Savers Exchange was first mooted in May 2024, but having just made a long road trip across Utah and Colorado, I really didn’t want to get behind the wheel again. However, we had no epic road trip plans this year, so I decided to contact Executive Director,  So I asked Mike if we could have a ‘behind-the-scenes’ visit (not open to regular visitors), to learn about the organization in detail, and the management of such a large and diverse collection of plant species. He quickly agreed, and asked Director of Preservation,

So I asked Mike if we could have a ‘behind-the-scenes’ visit (not open to regular visitors), to learn about the organization in detail, and the management of such a large and diverse collection of plant species. He quickly agreed, and asked Director of Preservation,  Incidentally, Seed Savers Exchange also has a commercial arm (which supports its non-profit mission), selling seeds through an

Incidentally, Seed Savers Exchange also has a commercial arm (which supports its non-profit mission), selling seeds through an

Besides conserving the seeds and vegetatively-propagated species at Seed Savers Exchange, there is also coordination of the membership and Exchange (the gardener-to-gardener seed swap) a role that falls to Josie Flatgrad (right).

Besides conserving the seeds and vegetatively-propagated species at Seed Savers Exchange, there is also coordination of the membership and Exchange (the gardener-to-gardener seed swap) a role that falls to Josie Flatgrad (right).

So, who is

So, who is

As billionaire entrepreneur

As billionaire entrepreneur  It’s beyond comprehension that, seemingly on a whim, DOGE abolished the world’s biggest (although not meeting the UN target of 0.7% of Gross National Income or GNI) and perhaps most important development agency, the United States Agency for International Development or USAid (now subsumed into the State Department).

It’s beyond comprehension that, seemingly on a whim, DOGE abolished the world’s biggest (although not meeting the UN target of 0.7% of Gross National Income or GNI) and perhaps most important development agency, the United States Agency for International Development or USAid (now subsumed into the State Department).

varieties. But on 13 February she, like tens of thousands of other recent hires across the government still in probationary status, was dismissed from her job. [2]

varieties. But on 13 February she, like tens of thousands of other recent hires across the government still in probationary status, was dismissed from her job. [2] from the

from the

Memories. Powerful; fleeting; joyful; or sad. Sometimes, unfortunately, too painful and hidden away in the deepest recesses of the mind, only to be dragged to the surface with great reluctance.

Memories. Powerful; fleeting; joyful; or sad. Sometimes, unfortunately, too painful and hidden away in the deepest recesses of the mind, only to be dragged to the surface with great reluctance.

I grew up believing that—despite the suitability or not of the occupant—one should respect the office of a Prime Minister or President.

I grew up believing that—despite the suitability or not of the occupant—one should respect the office of a Prime Minister or President.

And he unleashed mad dogs in the form of Elon Musk and his cohort of employees from the so-called ‘Department for Government Efficiency’ (DOGE) with, it seems, carte blanche authority to do whatever he pleases.

And he unleashed mad dogs in the form of Elon Musk and his cohort of employees from the so-called ‘Department for Government Efficiency’ (DOGE) with, it seems, carte blanche authority to do whatever he pleases.

It was about the

It was about the

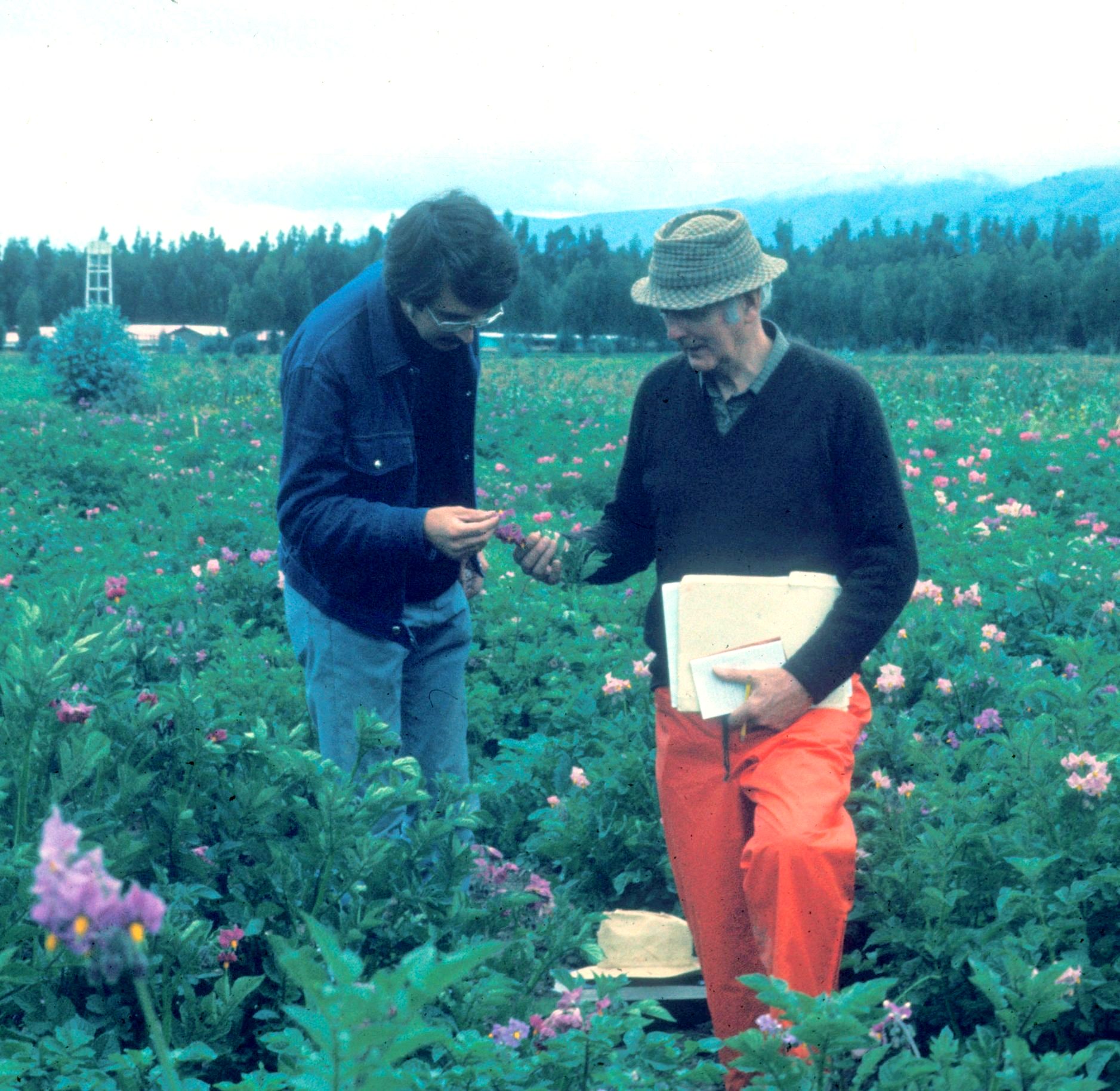

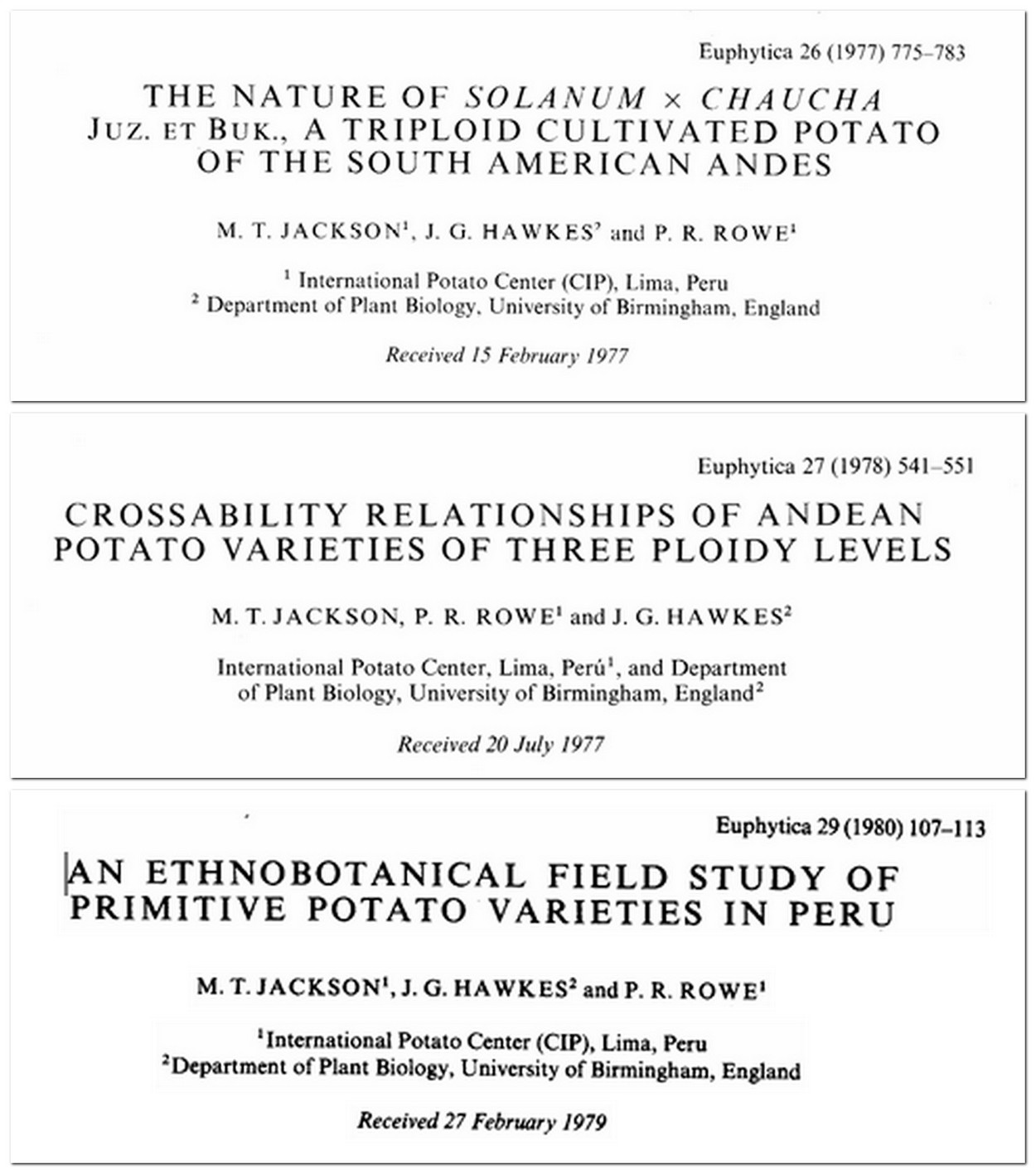

Among the species identified in the course of Jack’s dissertation research was Solanum ballsii from northern Argentina, which he dedicated to EK Balls in a formal description in 1944. However, in his 1963 revised taxonomy of the tuber-bearing Solanums (potatoes), Jack (with his Danish colleague Jens Peter Hjerting, 1917-2012) recognized Solanum ballsii simply as a subspecies of Solanum vernei, a species which has since provided many important sources of resistance to the potato cyst nematode.

Among the species identified in the course of Jack’s dissertation research was Solanum ballsii from northern Argentina, which he dedicated to EK Balls in a formal description in 1944. However, in his 1963 revised taxonomy of the tuber-bearing Solanums (potatoes), Jack (with his Danish colleague Jens Peter Hjerting, 1917-2012) recognized Solanum ballsii simply as a subspecies of Solanum vernei, a species which has since provided many important sources of resistance to the potato cyst nematode.

Before those two concerts it must have been almost 30+ years since I’d attended any live concert, while I was still at university.

Before those two concerts it must have been almost 30+ years since I’d attended any live concert, while I was still at university.

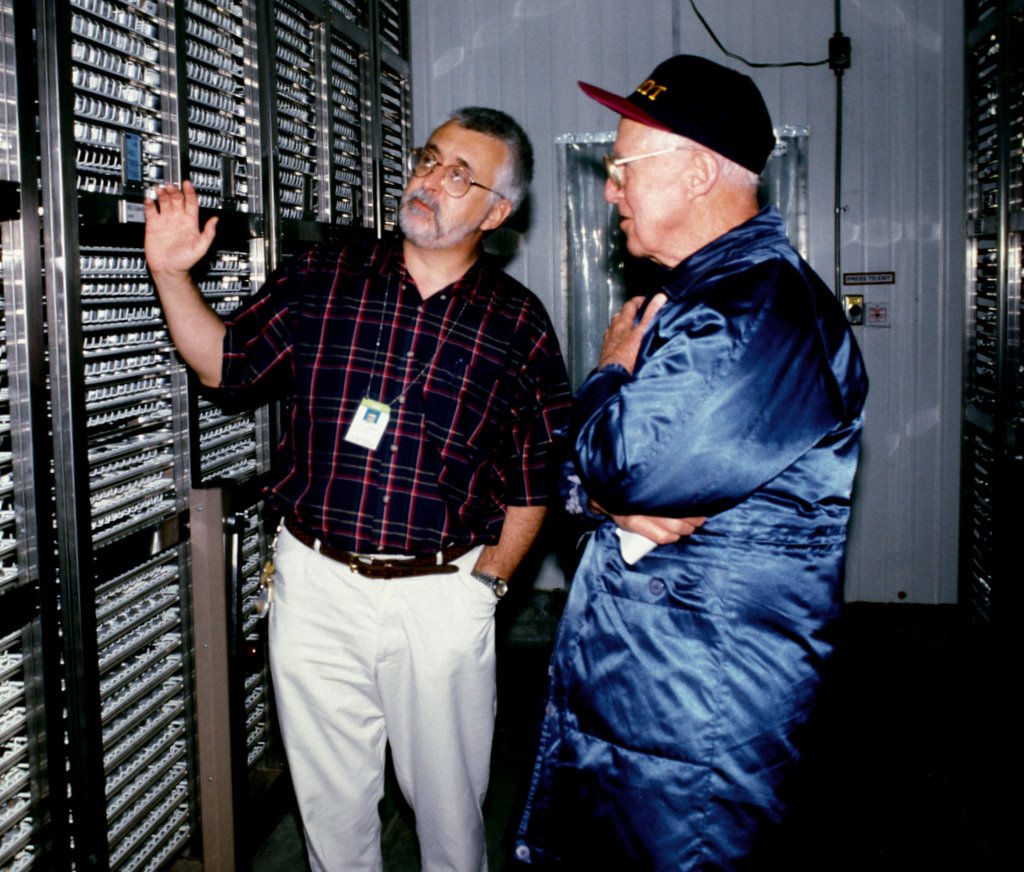

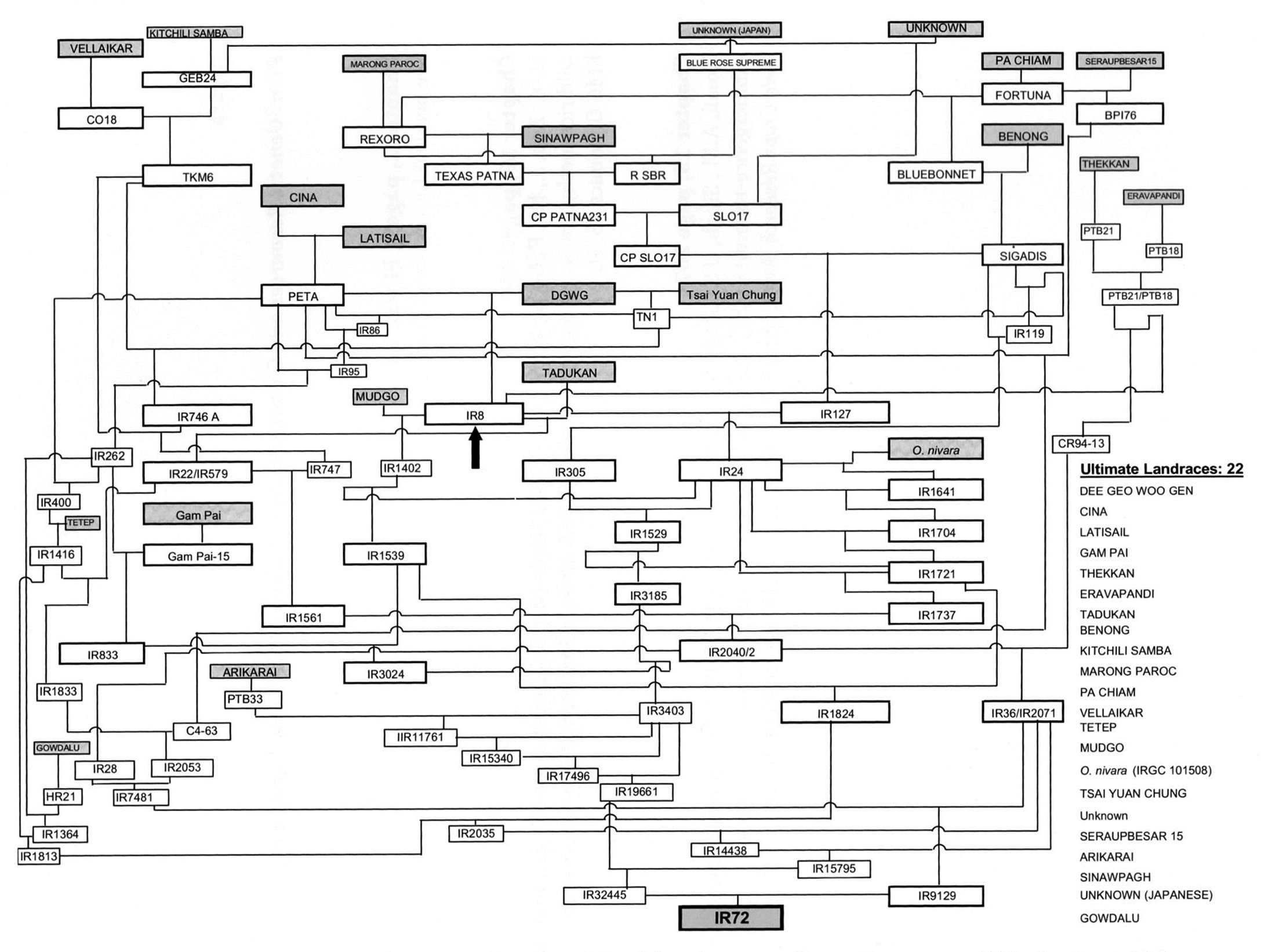

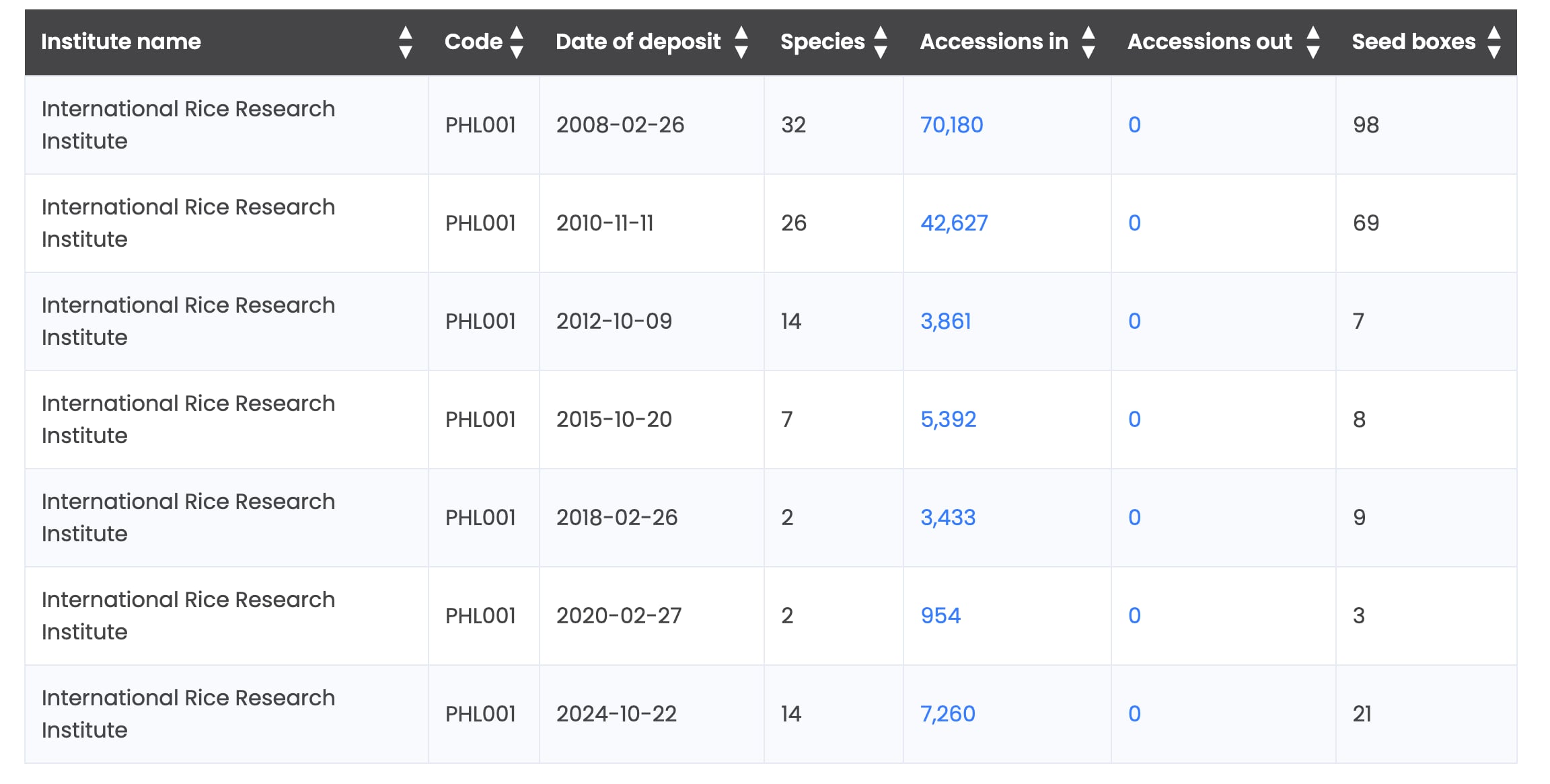

Since I started this blog in February 2012, I have written a number of stories about rice genetic resources and their conservation at the

Since I started this blog in February 2012, I have written a number of stories about rice genetic resources and their conservation at the

During the 1990s, the collection grew by about 30% to a little over 100,000 accessions. This was quite remarkable in itself, given that the

During the 1990s, the collection grew by about 30% to a little over 100,000 accessions. This was quite remarkable in itself, given that the

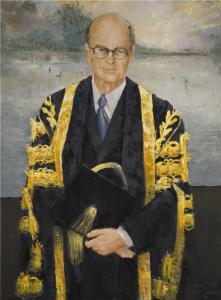

1991 was a fortuitous time to join IRRI. I was recruited by Director General

1991 was a fortuitous time to join IRRI. I was recruited by Director General

Earlier I mentioned the CBD. There’s no doubt that during the 1990s the whole realm of genetic resources became highly politicized, with the CGIAR centers contributing to CBD discussions as they related to agricultural biodiversity, and through the

Earlier I mentioned the CBD. There’s no doubt that during the 1990s the whole realm of genetic resources became highly politicized, with the CGIAR centers contributing to CBD discussions as they related to agricultural biodiversity, and through the

attention as I was reading a book at the time. High brow Muzak.

attention as I was reading a book at the time. High brow Muzak. I was totally unaware of this interesting back story. Nevertheless, it is a beautiful and much appreciated piece of music, that gained position 170/300 in the Classic FM Hall of Fame 2024. Enjoy this interpretation.

I was totally unaware of this interesting back story. Nevertheless, it is a beautiful and much appreciated piece of music, that gained position 170/300 in the Classic FM Hall of Fame 2024. Enjoy this interpretation.

With some free time in Dublin, I took the opportunity of walking around the city center, and came across a record store on Grafton Street, where this recording of Orfeo ed Euridice was in stock. I also bought Mark Knopfler’s Golden Heart that had just been released. It’s remained a favorite of mine ever since.

With some free time in Dublin, I took the opportunity of walking around the city center, and came across a record store on Grafton Street, where this recording of Orfeo ed Euridice was in stock. I also bought Mark Knopfler’s Golden Heart that had just been released. It’s remained a favorite of mine ever since.

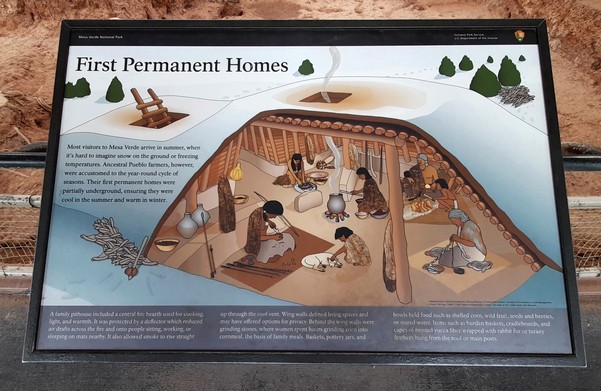

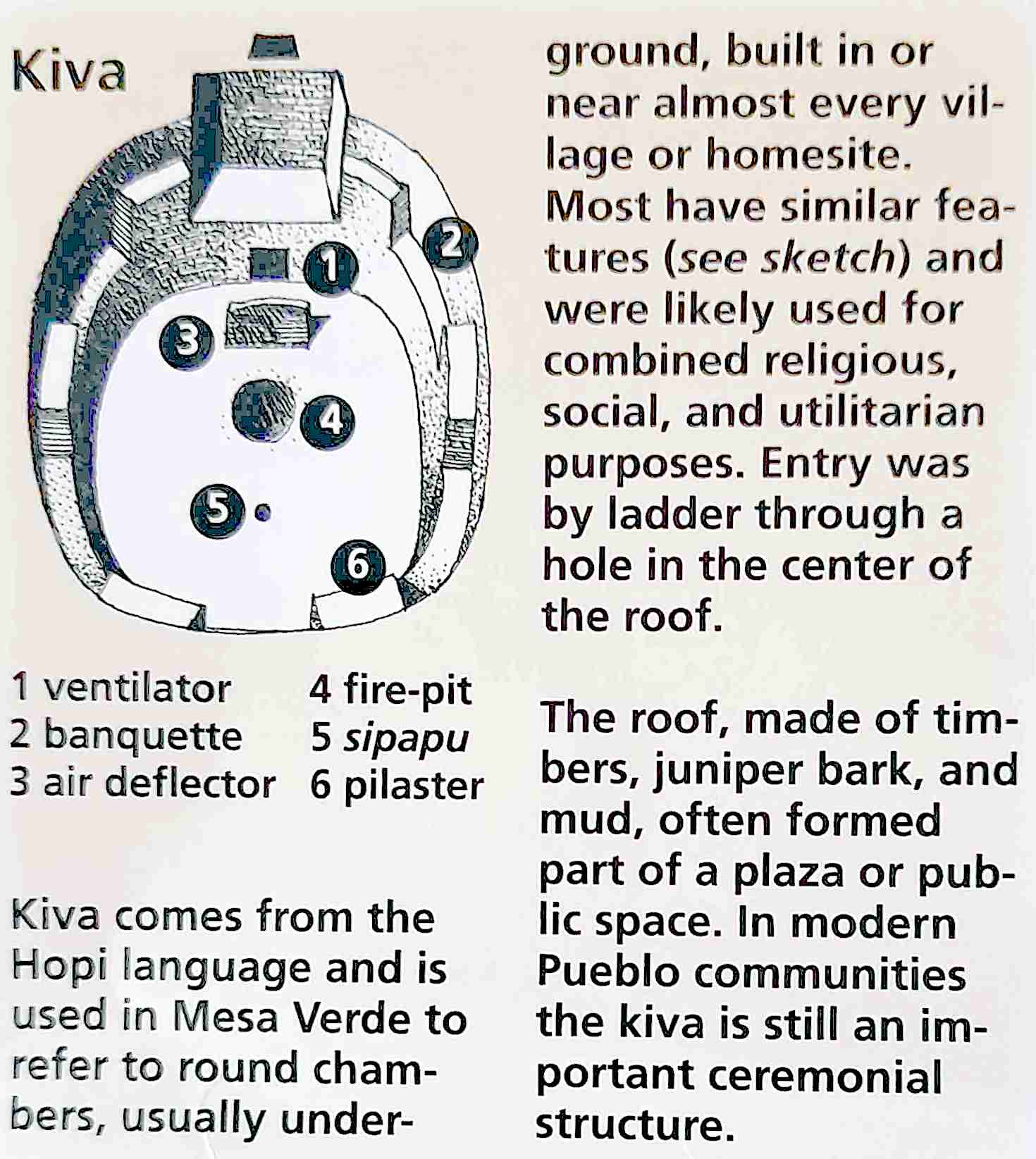

The day after visiting Mesa Verde, we set off early from Durango to cross the mountains east of Pagosa Springs, before heading northeast to Cañon City.

The day after visiting Mesa Verde, we set off early from Durango to cross the mountains east of Pagosa Springs, before heading northeast to Cañon City.

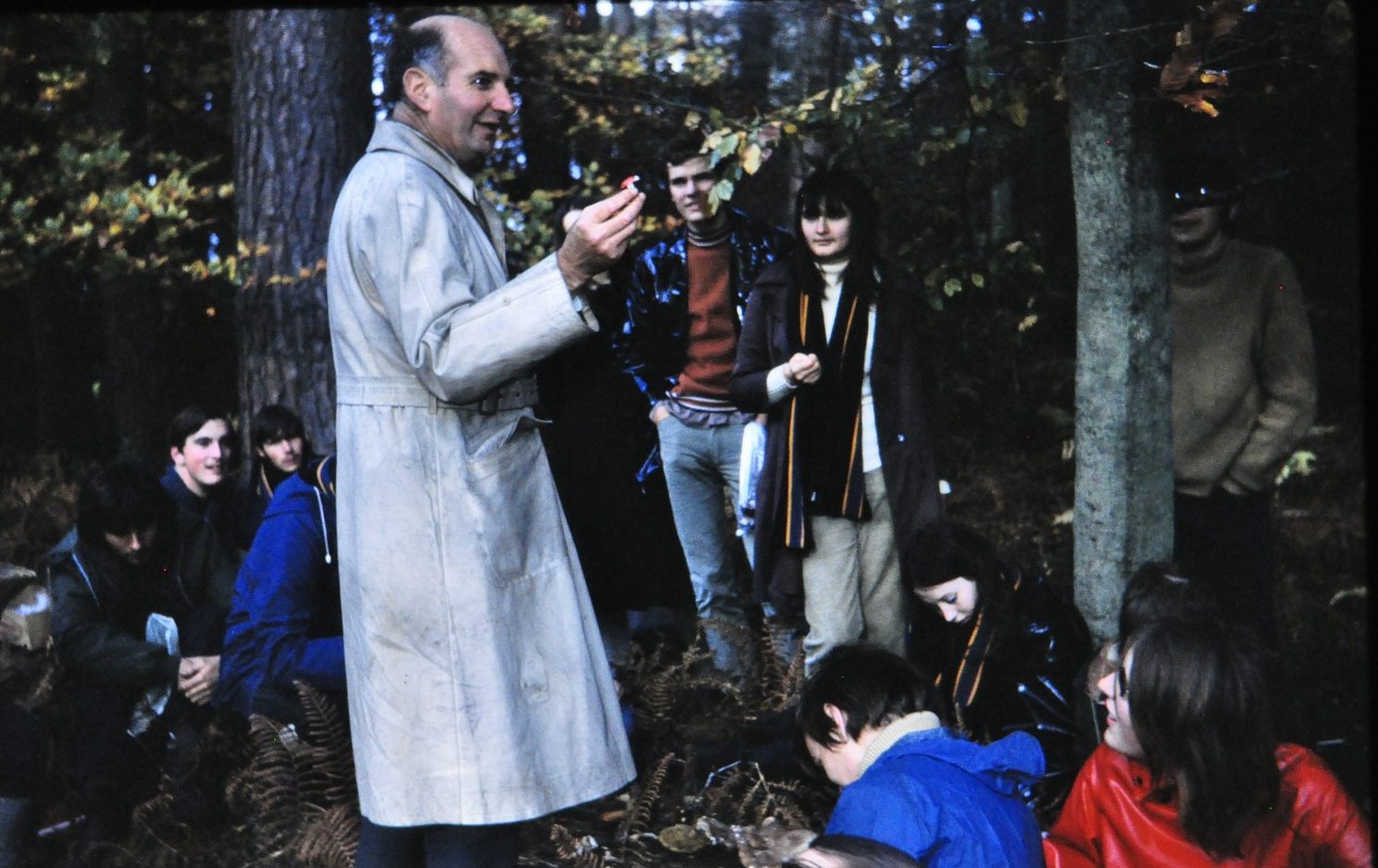

For 20 years before I joined the

For 20 years before I joined the

The CGIAR’s

The CGIAR’s

The next step was to expand the research in Los Baños itself looking at more rice varieties in a real rice-growing environment.

The next step was to expand the research in Los Baños itself looking at more rice varieties in a real rice-growing environment.

Yvette completed her MS degree at the University of the Philippines-Los Baños, co-supervised by me and a faculty member from the university, for a study on two distantly related species, Oryza ridleyi and Oryza longiglumis. Some years later she went on to complete her PhD as well.

Yvette completed her MS degree at the University of the Philippines-Los Baños, co-supervised by me and a faculty member from the university, for a study on two distantly related species, Oryza ridleyi and Oryza longiglumis. Some years later she went on to complete her PhD as well.

In Asia, few collections of rice germplasm had been made in Laos, due to the conflict that had blighted that country over many years. In fact it’s overall capacity for agricultural R&D was quite limited. At the end of the 1980s, and supported with Swiss funding, IRRI opened a country program office in Vientiane (the capital city), headed by the late Dr John Schiller (right), an Australian agronomist who became a good friend.

In Asia, few collections of rice germplasm had been made in Laos, due to the conflict that had blighted that country over many years. In fact it’s overall capacity for agricultural R&D was quite limited. At the end of the 1980s, and supported with Swiss funding, IRRI opened a country program office in Vientiane (the capital city), headed by the late Dr John Schiller (right), an Australian agronomist who became a good friend. Dr Seepana Appa Rao (right, a germplasm scientist) came to us from a sister center, ICRISAT, in Hyderabad, India and he spent five years in Laos, assembling a comprehensive collection of 13,000 Lao rice samples which were duplicated in the International Rice Genebank. I wrote about this special aspect of the rice biodiversity project

Dr Seepana Appa Rao (right, a germplasm scientist) came to us from a sister center, ICRISAT, in Hyderabad, India and he spent five years in Laos, assembling a comprehensive collection of 13,000 Lao rice samples which were duplicated in the International Rice Genebank. I wrote about this special aspect of the rice biodiversity project

My Filipino staff grew in their roles, and the genebank went from strength to strength. I retired just as IRRI reached its Golden Jubilee.

My Filipino staff grew in their roles, and the genebank went from strength to strength. I retired just as IRRI reached its Golden Jubilee.

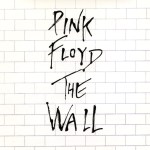

As I was unpacking my suitcase, I’d turned on the TV, and whatever channel I’d tuned to (my recollection was MTV, but I’ve checked and MTV wasn’t launched until 1981) was broadcasting a rather interesting video, of cartoon hammers marching in step—in the last minute of

As I was unpacking my suitcase, I’d turned on the TV, and whatever channel I’d tuned to (my recollection was MTV, but I’ve checked and MTV wasn’t launched until 1981) was broadcasting a rather interesting video, of cartoon hammers marching in step—in the last minute of  Just yesterday, I came across a video on YouTube, by American YouTube personality, multi-instrumentalist, music producer, and educator,

Just yesterday, I came across a video on YouTube, by American YouTube personality, multi-instrumentalist, music producer, and educator,