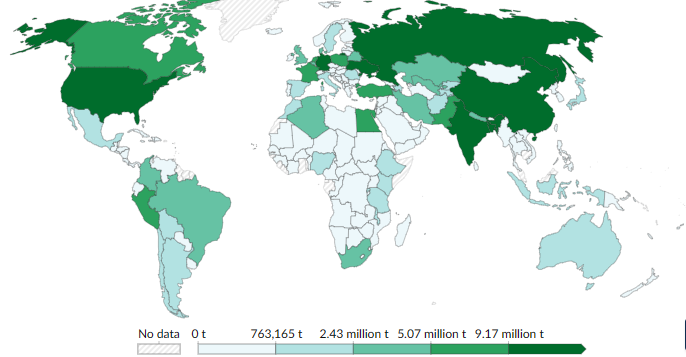

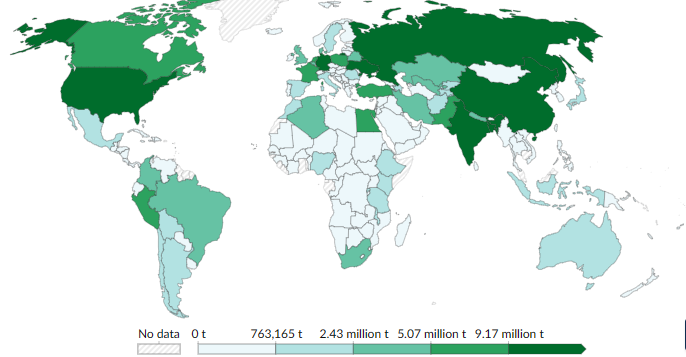

Not so humble really. The potato is an incredibly important crop worldwide (the fourth, after maize, rice, and wheat), with a production of 376 million metric tonnes in 2021. China is the leading producer, with 95.5 million metric tonnes, followed by India, Ukraine, Russia, and the USA.

Potato production in 2022

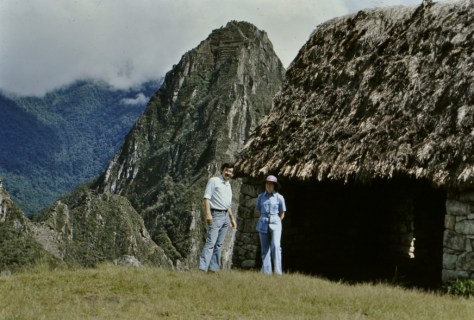

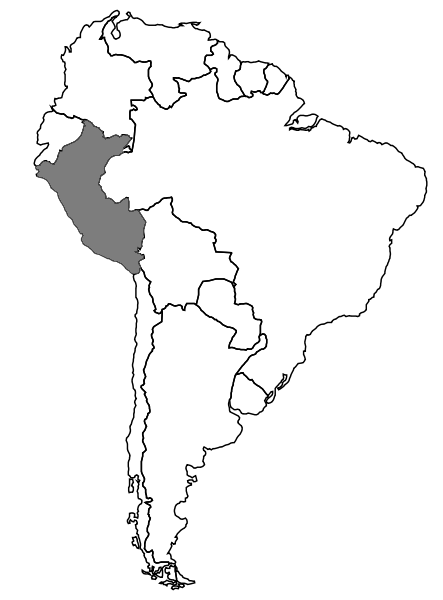

Native to and a staple food in the Andean countries of South America, the potato spread to Spain in the 16th century [1, 2] and the rest of the world afterwards.

It’s no wonder that Peru championed the International Day of the Potato (decreed by the United Nations in December 2023 [3]) which is being celebrated today.

I thought this would be an excellent opportunity to reflect on my own journey with potatoes over 20 years in the 1970s and 1980s.

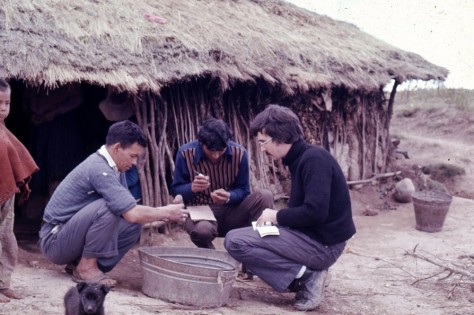

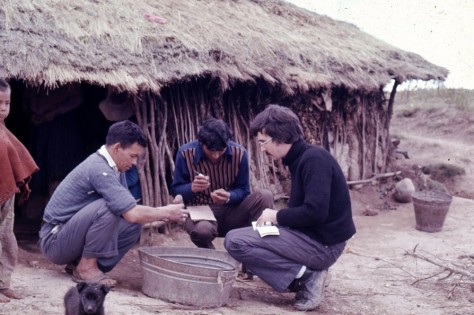

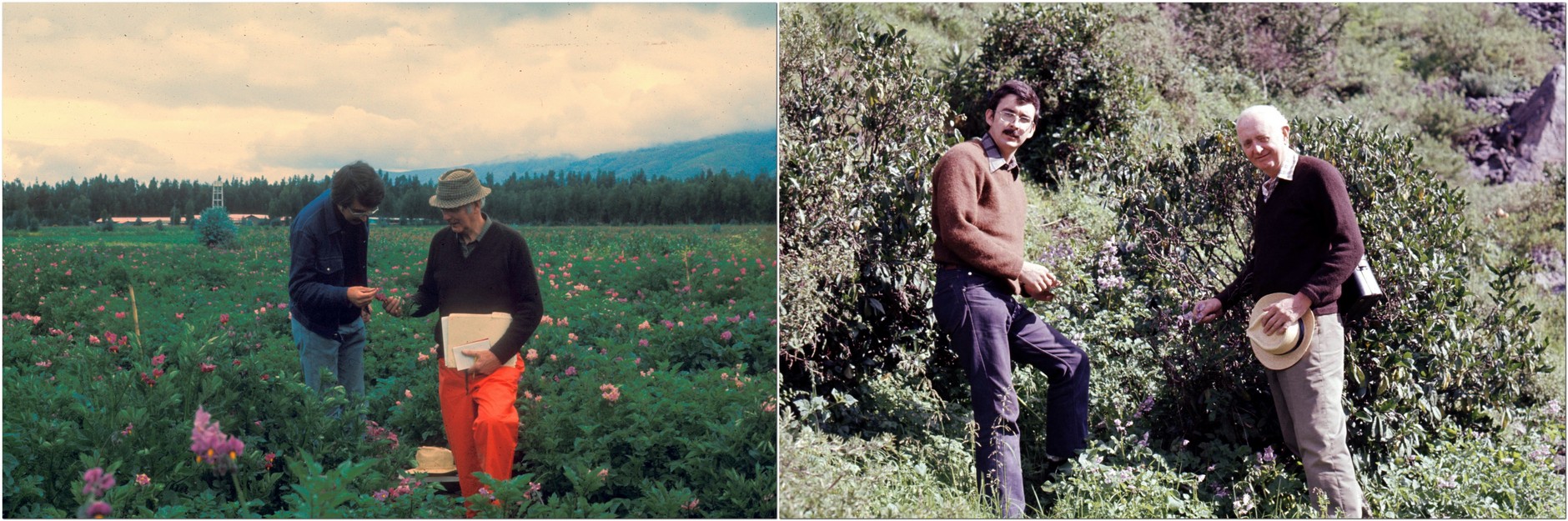

Fifty years ago (in May 1974) I had just returned to Lima after collecting potatoes for three weeks in the north of Peru (Department of Cajamarca), accompanied by my driver, Octavio.

A farmer in Cajamarca discusses his potato varieties with me, while my driver Octavio writes a collecting number on each tuber and a paper bag with a permanent marker pen.

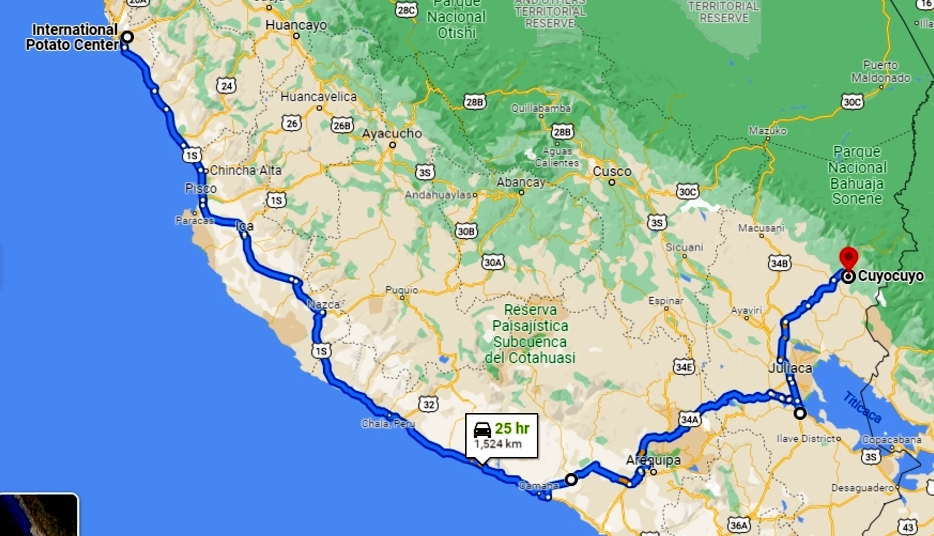

A few months earlier, at the beginning of February, I’d travelled to Cuyo Cuyo (Department of Puno in southern Peru) to make a study of potato varieties in farmers’ fields on the ancient terraces there (below).

So what was I doing in Peru?

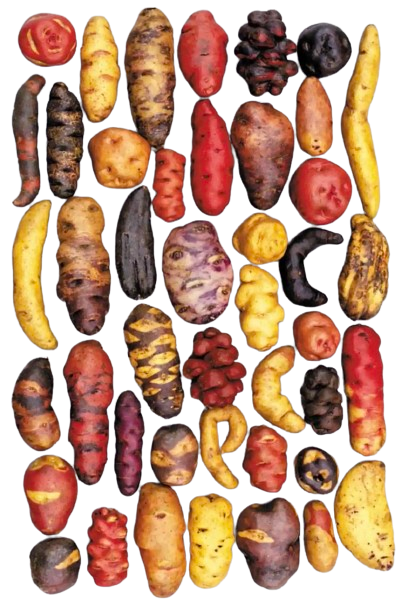

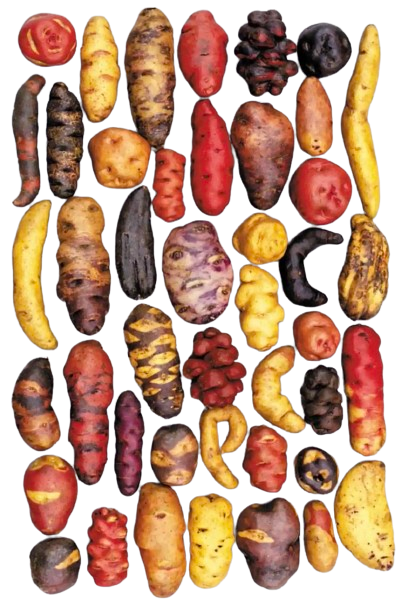

I’d joined the International Potato Center (CIP) in Lima the previous year, in January 1973 [4] as an Associate Taxonomist while continuing with my PhD research. And I found myself, a few months later—in May—travelling with with my colleague Zosimo Huamán (right) to the northern departments of Ancash and La Libertad where, over almost a month, we collected many indigenous potato varieties—the real treasure of the Incas— that were added to CIP’s growing germplasm collection. Here are just a few examples of the incredible diversity of Andean potato varieties in that collection. Maybe I collected some of these.

I’d joined the International Potato Center (CIP) in Lima the previous year, in January 1973 [4] as an Associate Taxonomist while continuing with my PhD research. And I found myself, a few months later—in May—travelling with with my colleague Zosimo Huamán (right) to the northern departments of Ancash and La Libertad where, over almost a month, we collected many indigenous potato varieties—the real treasure of the Incas— that were added to CIP’s growing germplasm collection. Here are just a few examples of the incredible diversity of Andean potato varieties in that collection. Maybe I collected some of these.

Source: International Potato Center (CIP)

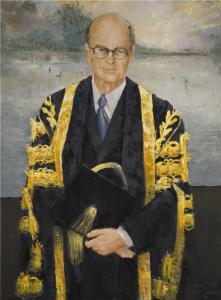

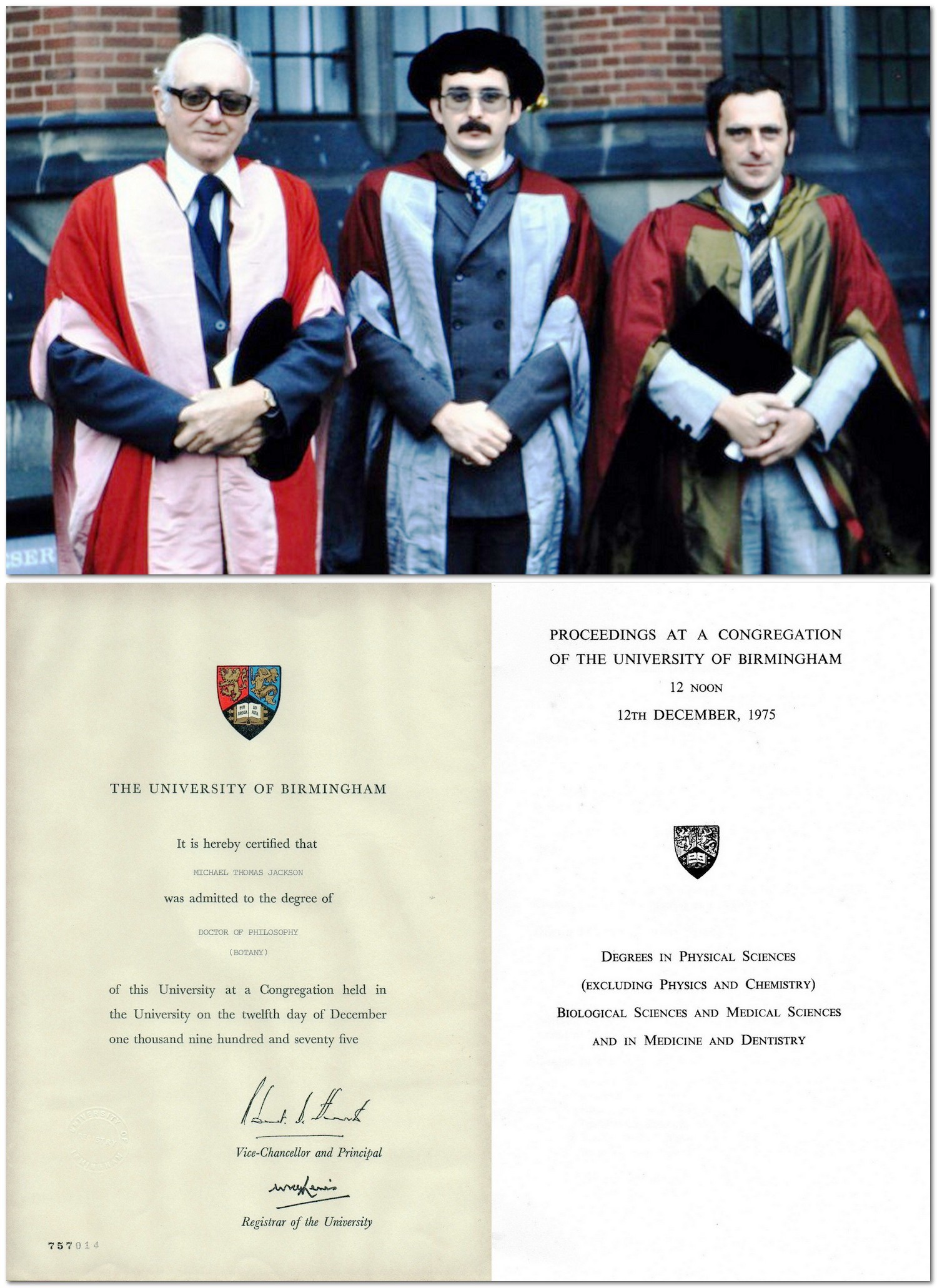

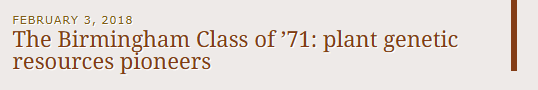

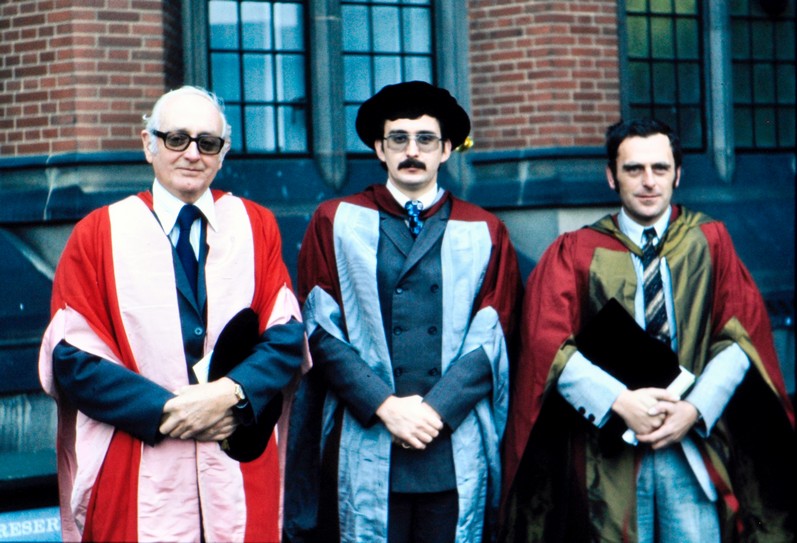

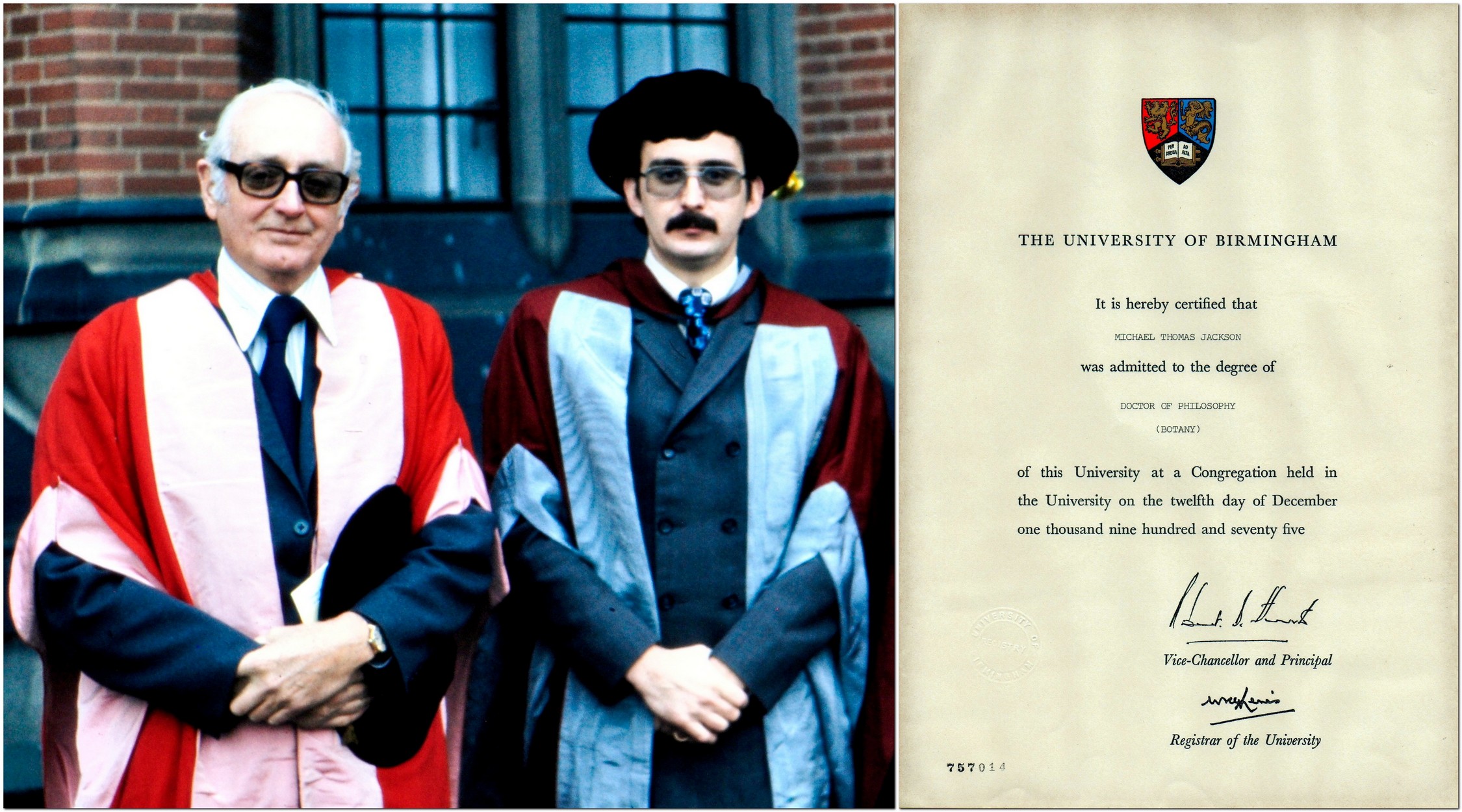

In October 1975, I successfully defended my PhD thesis (The evolutionary significance of the triploid cultivated potato, Solanum x chaucha Juz. et Buk.) at the University of Birmingham, where my co-supervisor, potato taxonomist and germplasm pioneer Professor Jack Hawkes (right) was head of the Department of Botany.

In October 1975, I successfully defended my PhD thesis (The evolutionary significance of the triploid cultivated potato, Solanum x chaucha Juz. et Buk.) at the University of Birmingham, where my co-supervisor, potato taxonomist and germplasm pioneer Professor Jack Hawkes (right) was head of the Department of Botany.

During my time in Lima, Dr Roger Rowe (left, then head of CIP’s Breeding and Genetics Department) was my local supervisor.

During my time in Lima, Dr Roger Rowe (left, then head of CIP’s Breeding and Genetics Department) was my local supervisor.

Fifty years after I first met Roger in Peru, we had a reunion on the banks of the Mississippi in Wisconsin last year.

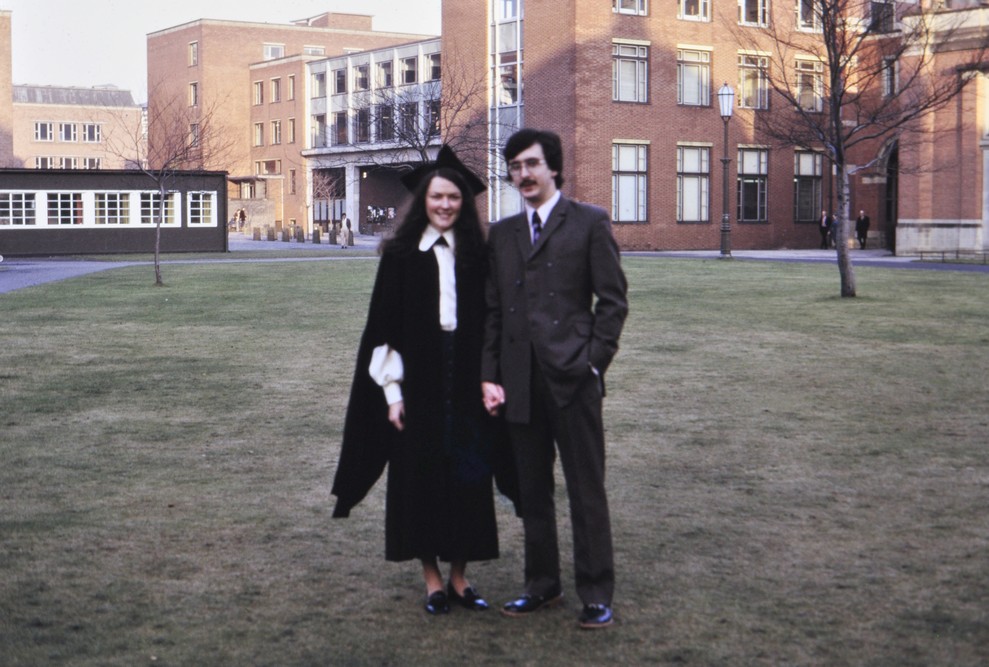

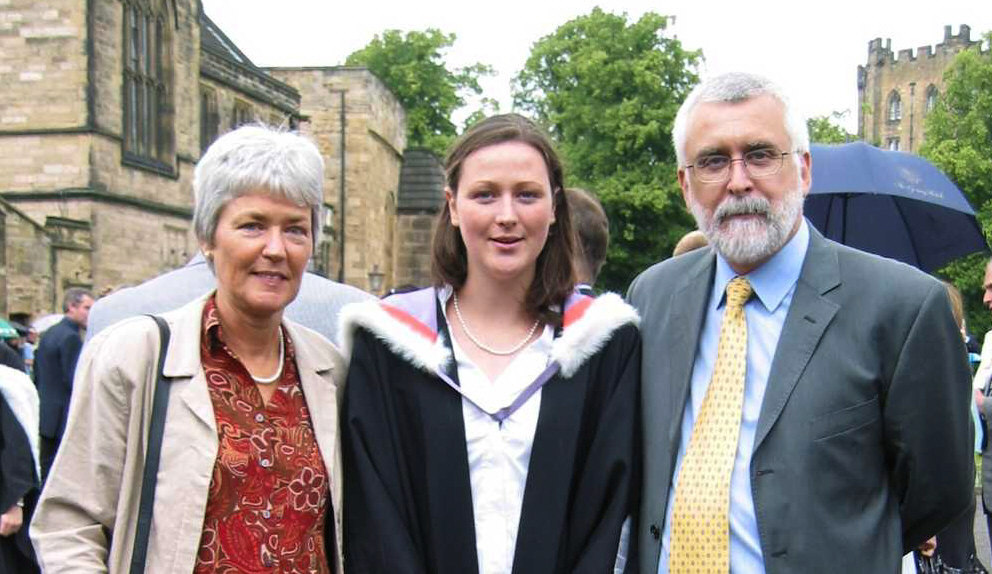

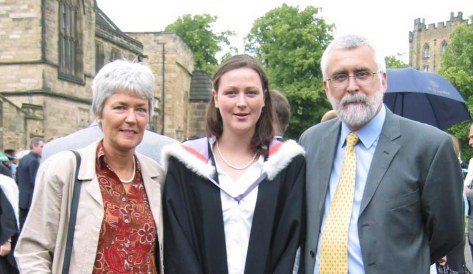

After the University of Birmingham congregation on 12 December 1975, with Jack Hawkes on my right, and Professor Trevor Williams (who supervised my MSc dissertation in 1971) on my left.

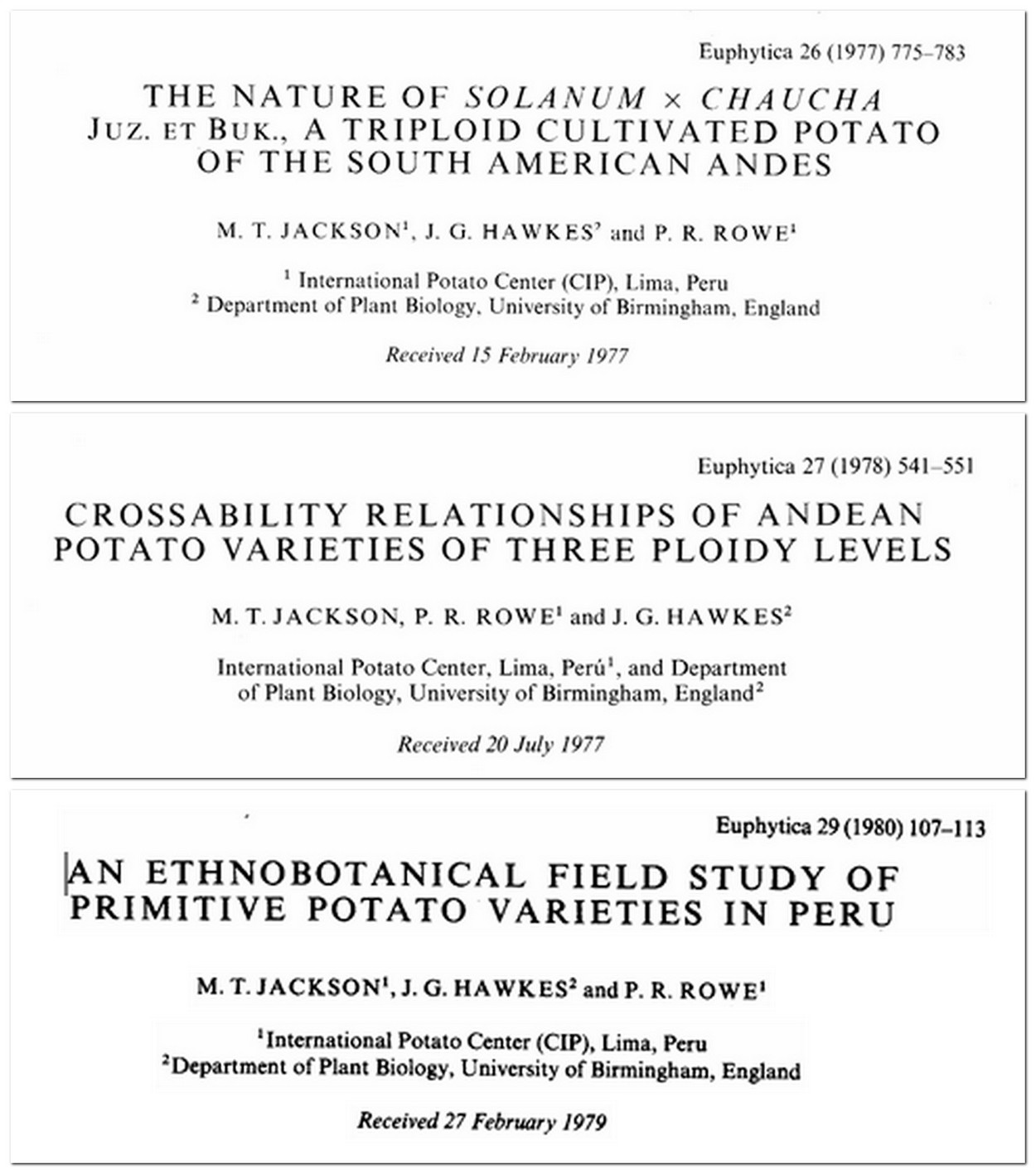

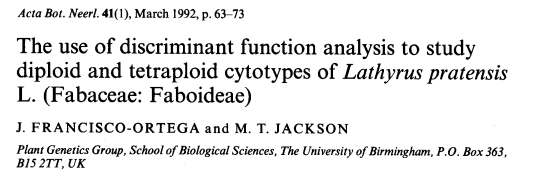

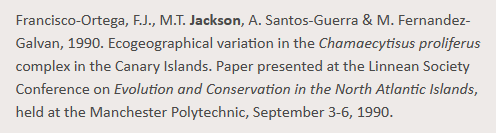

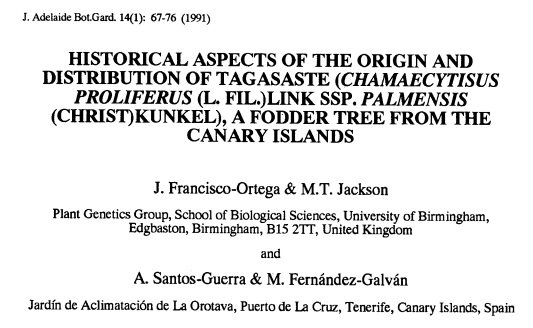

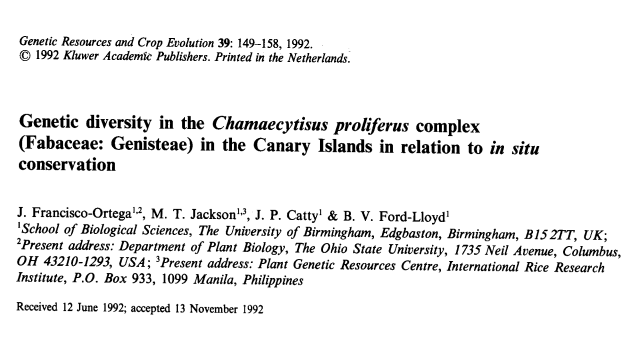

I published three papers from my thesis. Click on any title image below (and most others throughout this post) to read the full paper.

There’s an interesting story behind the publication of this third paper from my thesis.

I originally sent a manuscript to Economic Botany, probably not long after I’d submitted the others to Euphytica.

I received an acknowledgment from Economic Botany, but then it went very quiet for at least a year.

Anyway, towards the end of 1978 or early 1979 I received—quite out of the blue—a letter from the then editor-in-chief of Euphytica, Professor AC Zeven. He told me he’d read my thesis, a copy of which had been acquired apparently by the Wageningen University library. He liked the chapter I’d written about an ethnobotanical study in Cuyo-Cuyo, and if I hadn’t submitted a paper elsewhere, he would welcome one from me.

It was about that same time I also received a further communication from the incoming editor of Economic Botany, who had found papers submitted to the journal up to 20 years previously and still waiting publication, and was I still interested in continuing with the Economic Botany submission, since he was unable to say when or if my manuscript might be considered for publication. I immediately withdrew the manuscript and, after some small revisions to fit the Euphytica style and focus, sent the manuscript to Professor Zeven. It was published in February 1980.

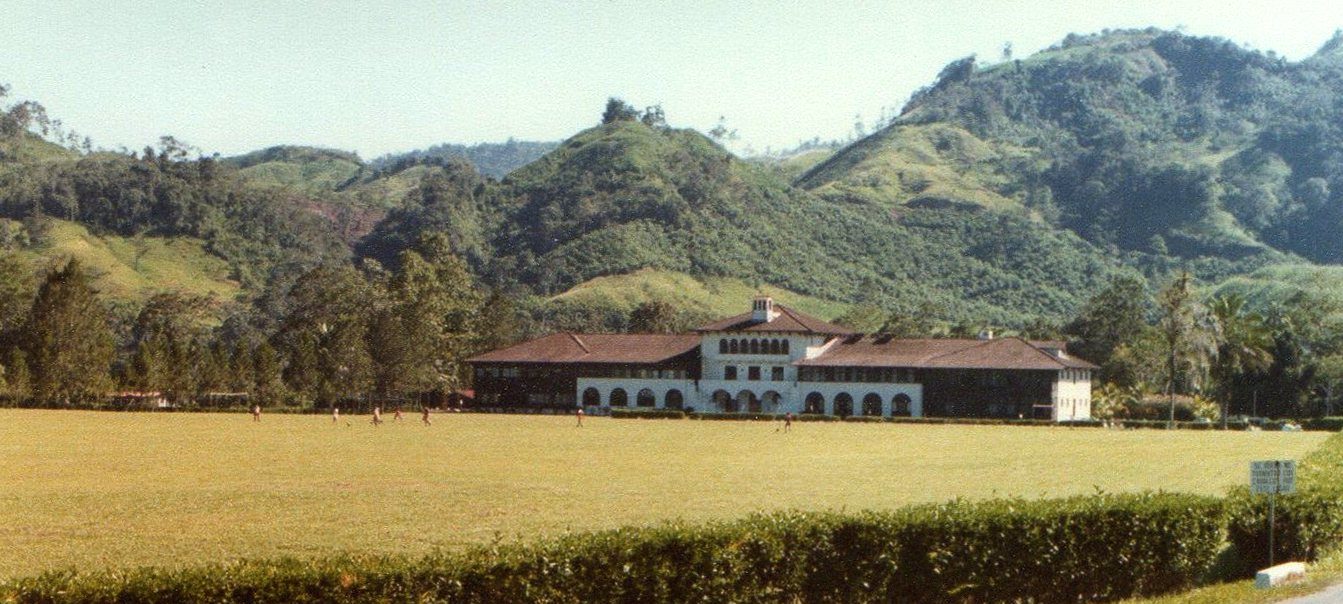

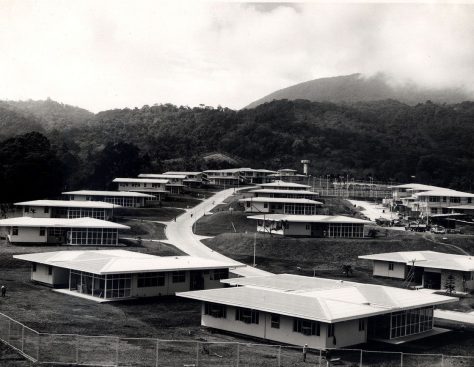

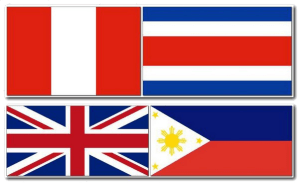

I returned to Lima just before the New Year 1976, knowing that CIP’s Director General, Dr Richard Sawyer (right), had already approved my transfer to CIP’s Outreach Program (later renamed Regional Research). I relocated to Costa Rica in Central America in April 1976 (living and working at the Tropical Agricultural Research and Higher Education Center, CATIE in Turrialba), establishing a program to adapt potatoes to the warm humid tropics. I became leader of CIP’s regional program (or Regional Representative) in late 1977.

I returned to Lima just before the New Year 1976, knowing that CIP’s Director General, Dr Richard Sawyer (right), had already approved my transfer to CIP’s Outreach Program (later renamed Regional Research). I relocated to Costa Rica in Central America in April 1976 (living and working at the Tropical Agricultural Research and Higher Education Center, CATIE in Turrialba), establishing a program to adapt potatoes to the warm humid tropics. I became leader of CIP’s regional program (or Regional Representative) in late 1977.

However, the tropical adaptation objective per se didn’t exactly endure. The potato trials were almost immediately attacked by bacterial wilt (caused by Ralstonia solaneacearum, formerly known as Pseudomonas solanacearum) even though no susceptible crops such as tomatoes had been planted on the CATIE experiment station in recent years. We subsequently discovered that the bacterium survived in a number of non-solanaceous weed hosts.

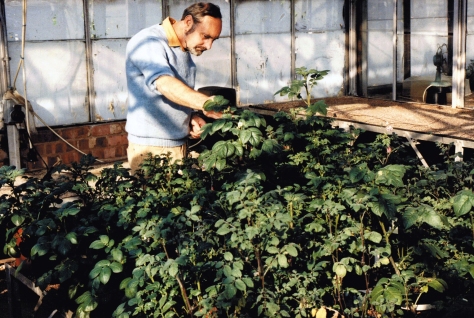

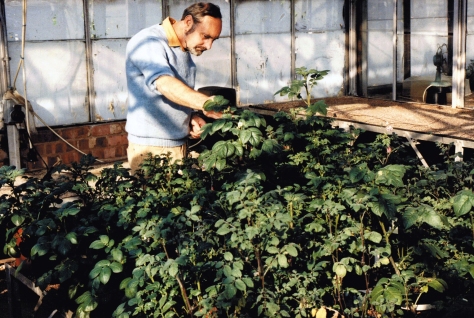

Screening for bacterial wilt resistance in CATIE’s experiment station.

I’ve posted earlier about our research on bacterial wilt and finding tolerance to the disease in a potato clone (not quite a commercial variety) known simply as Cruza 148.

Plant pathologist Professor Luis Carlos Gonzalez (right, from the University of Costa Rica in San José) and I also studied how to control the disease through a combination of tolerant varieties and soil and weed management.

Plant pathologist Professor Luis Carlos Gonzalez (right, from the University of Costa Rica in San José) and I also studied how to control the disease through a combination of tolerant varieties and soil and weed management.

We published these two papers, the first in the international journal Phytopathology, and the second in the Costarrican journal Fitopatologia.

During the late 1970s, CIP launched an initiative aimed at optimising potato productivity, jointly led by Chilean agronomist Dr Primo Accatino and US agricultural economist Dr Doug Horton. Contributing to this initiative in Costa Rica, I worked with potato farmers to reduce the excessive use of fertilizers, and fungicides to control the late blight pathogen, Phytophthora infestans. It was then (and probably remains) a common misconception among farmers that more input of fertilizer or fungicide, the better would be the outcome in terms of yield or disease control. What a fallacy! Our small project on fertilizer use was published in Agronomía Costarricense.

During the five years I spent in Costa Rica, my colleagues in the Ministerio de Agricultura y Ganadería (MAG) and I screened germplasm sent to us by CIP breeders in Lima for resistance to late blight, and common potato viruses like PVX, PVY, PLRV.

Ing. Jorge Esquivel (MAG) and me screening potatoes for virus resistance in a field trial on the slopes of the Irazú volcano in Costa Rica, while my assistants Jorge Aguilar and Moisés Pereira check plants nearby.

In 1977, Dr John Niederhauser (right, an eminent plant pathologist who had worked on late blight in Mexico for the Rockefeller Foundation before becoming an international consultant to CIP) and I worked together to develop and implement (from April 1978) a cooperative regional potato program, PRECODEPA, in six countries: Mexico, Guatemala, Honduras, Costa Rica, Panama, and the Dominican Republic. Funded by the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation, SDC (and for the next 25 years or so, and expanded to more countries in the region), the network was a model for regional collaboration, with members contributing research based on their particular scientific strengths.

In 1977, Dr John Niederhauser (right, an eminent plant pathologist who had worked on late blight in Mexico for the Rockefeller Foundation before becoming an international consultant to CIP) and I worked together to develop and implement (from April 1978) a cooperative regional potato program, PRECODEPA, in six countries: Mexico, Guatemala, Honduras, Costa Rica, Panama, and the Dominican Republic. Funded by the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation, SDC (and for the next 25 years or so, and expanded to more countries in the region), the network was a model for regional collaboration, with members contributing research based on their particular scientific strengths.

Clean seed tubers are one of the most important components for successful potato production, and technologies to scale up the multiplication of clean seed were contributed by CIP to PRECODEPA. My colleague from Lima, Jim Bryan (an Idaho-born seed production specialist) joined me in Costa Rica in 1979 for one year, and together we successfully developed several rapid multiplication techniques, including stem cuttings and leaf node cuttings, and producing a technical bulletin (published also in Spanish).

Clean seed tubers are one of the most important components for successful potato production, and technologies to scale up the multiplication of clean seed were contributed by CIP to PRECODEPA. My colleague from Lima, Jim Bryan (an Idaho-born seed production specialist) joined me in Costa Rica in 1979 for one year, and together we successfully developed several rapid multiplication techniques, including stem cuttings and leaf node cuttings, and producing a technical bulletin (published also in Spanish).

And we showed that it was possible to produce one tonne in a year from a single tuber. Read all about that effort here.

I can’t finish this section about my time at CIP without mentioning Dr Ken Brown (left), who was head of Regional Research.

I can’t finish this section about my time at CIP without mentioning Dr Ken Brown (left), who was head of Regional Research.

Ken, a cotton physiologist, joined CIP in January 1976 as head of Regional Research, just at the time Steph and I returned to Lima after I’d completed my PhD. He was one of the best program managers I have worked for, keeping everything on track, but never micro-managing. I learnt a great deal from Ken about managing staff, and getting the best out of them.

At the end of November 1980, I returned to Lima expecting to be posted to the Philippines. Instead, in March 1981, I resigned from CIP and accepted a lectureship in plant biology at the University of Birmingham, continuing potato research there, as well as working on several legume species.

I look back on those formative CIP years with great appreciation: for all that I learned about potatoes and potato production, the incredible scientists from around the world I met and worked with, and the many friendships I made.

Jack Hawkes retired from the university in September 1982, having left behind his large collection of wild potatoes accumulated during several expeditions to the Americas, and a legacy of potato research on which I endeavoured to build.

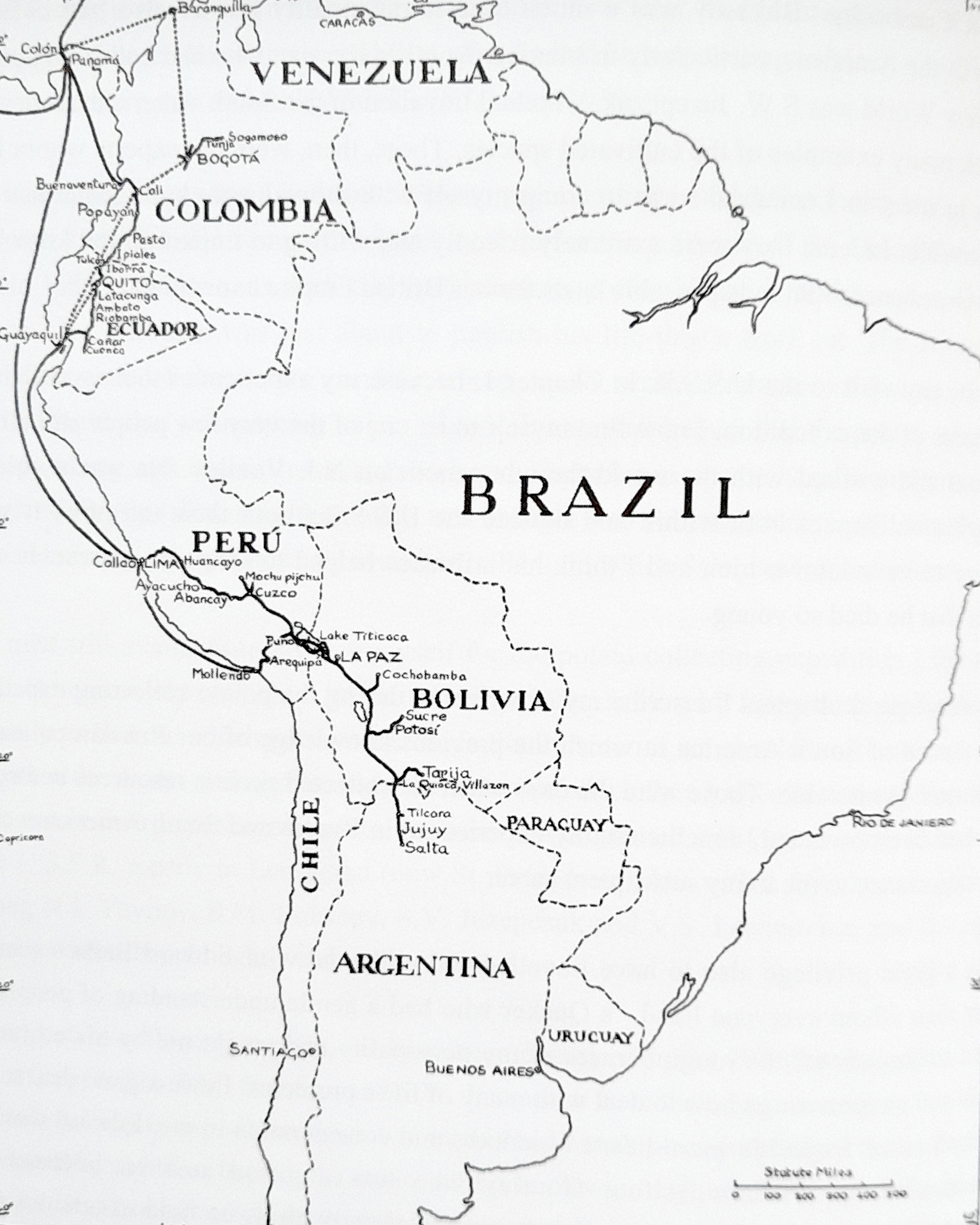

You can read all about Jack’s many expeditions, view many original photos, and watch several videos dating back to 1939 by clicking on the image below.

I soon realised there were few opportunities to continue research with Jack’s collection. It was almost impossible to secure funding. But I could offer short-term projects for MSc and PhD students.

Dave Downing was the technician managing the potato collection at Birmingham.

One MSc student, Susan Juned, studied the diversity in Solanum chacoense Bitt., a wild potato species from Argentina and Paraguay, in relation to in situ conservation opportunities.

Two MSc students from Uganda, Beatrice Male-Kayiwa and Nelson Wanyera evaluated resistance to potato cyst nematode (Globodera pallida) in wild potatoes from Bolivia. We asked Jack Hawkes to advise on the choice of germplasm to include, since he had made the collections in that country in the 1970s. Beatrice and Nelson worked at Rothamsted Experiment Station (now Rothamsted Research) in Hertfordshire with the late Dr Alan Stone.

Two PhD students, Lynne Woodwards and Ian Gubb, studied the lack of enzymic browning (potatoes turn brown when they are cut) in wild potatoes, Series Longipedicellata Buk., and one tetraploid (2n=4x=48 chromosomes) species from Mexico in particular, Solanum hjertingii Hawkes, and their crossability with cultivated potatoes. Ian’s studentship (co-supervised at Birmingham by Professor Jim Callow) involved a collaboration with the Institute of Food Research (now Quadram Institute Bioscience) in Norwich, where his co-supervisor was Dr JC Hughes.

Gene editing has recently successfully produced non-browning potatoes. Wide crossing is probably no longer needed.

I had two PhD students from Peru, René Chavez and Carlos Arbizu, who carried out their research at CIP (like I had in the early 1970s) and only came back to Birmingham to complete their residency requirements and defend their theses, although I visited them in Lima several times during their research.

René evaluated the breeding potential of wild species of potato for resistance to potato cyst nematodes and tuber moth, publishing three excellent papers from his thesis The use of wide crosses in potato breeding, submitted in 1984.

Carlos submitted his thesis, The use of Solanum acaule as a source of resistance to potato spindle tuber viroid (PSTV) and potato leaf roll virus (PLRV), in 1990. He never published any papers from his research, returning to Lima to work at CIP for a few years on Andean minor tuber crops, before setting himself up as a major avocado producer in Peru.

Denise Clugston (co-supervised by Professor Brian Ford-Lloyd) defended her thesis, Embryo culture and protoplast fusion for the introduction of Mexican wild species germplasm into the cultivated potato in 1988. She left biology almost immediately, and regrettably never did write any papers, although she did present this work at a conference held in Cambridge.

Another PhD student, Elizabeth Newton, worked on sexually-transmitted potato viruses of quarantine significance in the UK, in collaboration with one of my former colleagues at CIP, Dr Roger Jones who had returned to the UK and was working for the Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food (MAFF) at the Harpenden Laboratory. In 1989 she successfully submitted her thesis, Studies towards the control of viruses transmitted through true potato seed but never published any papers, only presenting this one at a conference in Warwick in 1986.

Because of the quarantine restrictions imposed on the Hawkes collection, I took the decision (with Jack’s blessing) to donate it to the Commonwealth Potato Collection in Dundee. Once the collection was gone, we had other opportunities for potato research at Birmingham.

Because of the quarantine restrictions imposed on the Hawkes collection, I took the decision (with Jack’s blessing) to donate it to the Commonwealth Potato Collection in Dundee. Once the collection was gone, we had other opportunities for potato research at Birmingham.

In the late 1980s, my colleague Brian Ford-Lloyd (right) and I ran a project, funded by KP Agriculture (and managed by my former CIP colleague, Dr John Vessey) to generate somaclonal lines resistant to low temperature sweetening of the crisping var. Record .

In the late 1980s, my colleague Brian Ford-Lloyd (right) and I ran a project, funded by KP Agriculture (and managed by my former CIP colleague, Dr John Vessey) to generate somaclonal lines resistant to low temperature sweetening of the crisping var. Record .

My former MSc student Susan Juned (right) was hired as a Research Associate.

We began the project with a batch of 170 Record tubers, uniquely numbering each one and keeping the identity of all somaclones derived from each tuber. And there were some interesting results (and an unexpected response from the media [5]).

Did the project meet its objectives? Well, this is what John later told us:

The project was successful in that it produced Record somaclones with lower reducing sugars in the tubers, but unsuccessful in that none entered commercial production . . . Shortly after the end of the project, Record was replaced by a superior variety, Saturna.

The project very clearly showed the potential of somaclones but also emphasised that it needs to be combined with conventional breeding . . . Other important aspects were the demonstration that the commercial seed potato lines available were not genetically identical, as previously thought, and that regeneration of clones from single cells had to be as rapid as possible to avoid unwanted somaclonal variation.

The majority of somaclones were derived from just a few of the 170 tubers, each potentially (and quite unexpectedly) a different Record clone. We suggested that the differential regeneration ability was due to genetic differences between tubers as it was found to be maintained in subsequent tuber generations. Furthermore, this would have major implications for seed potato production specifically and, more generally, for in vitro genetic conservation of vegetatively-propagated species.

Sue completed her PhD, Somaclonal variation in the potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) cultivar Record with particular reference to the reducing sugar variation after cold storage in 1994 after I’d already left Birmingham for the Philippines.

After leaving the university, Sue became a very successful local politician, even running in one General Election as a Liberal Democrat candidate for Parliament. Sue is now Leader of Stratford-on-Avon District Council.

From 1984, I had a project to work on true potato seed (or TPS) in collaboration with CIP, funded by the Overseas Development Administration (ODA, a UK government agency that eventually became the Department for International Development or DfID, but now fully subsumed into the Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office).

For many reasons, this project was not a success. Let me explain.

At the end of the 1970s CIP launched a project to use TPS as an alternative production approach to seed potatoes (i.e., tubers). But the use of TPS is not without its challenges.

Potato genetics are complex because most cultivated potatoes are polyploid, actually tetraploid with 48 chromosomes. And although self compatible, and producing copious quantities of TPS through self pollination, the progeny are highly variable. My approach was to produce uniform or homozygous diploid (with 24 chromosomes) inbred lines. The only obstacle being that diploid potatoes are self incompatible. We aimed to overcome that obstacle. There were precedents, albeit from a species in a totally unrelated plant family but with a similar incompatibility genetic base.

One of my colleagues at Birmingham, geneticist Dr Mike Lawrence spent many years working on field poppy (Papaver rhoeas) and, through persistent selfing, had manage to break its strong self incompatibility. We believed that a similar approach using single seed descent might yield dividends in diploid potatoes. Well, at least ODA felt it was worth a try, and the project had CIP’s backing (although not enthusiastically from the leading breeder there at the time). However, in the light of subsequent research, I think we have been vindicated in taking this particular approach.

Because of quarantine restrictions at Birmingham that I already mentioned, we negotiated an agreement with the Plant Breeding Institute (PBI) in Cambridge to base the project there, building a bespoke glasshouse for the research. My counterpart at PBI was the head of potato breeding, Dr Alan J Thomson. We hired a postdoc, recently graduated with a PhD from the University of St Andrews, who came with glowing references.

We set out our perspectives on inbreeding at a CIP planning conference in Lima.

I further elaborated on these perspectives in a book chapter (published in 1987) based on a paper I presented at a joint meeting of EAPR and EUCARPIA at King’s College, Cambridge, in December 1985.

Ultimately the project did not meet its main objective. We encountered three problems, even though making progress in the first three years:

- By year five, we really did hit a ‘biological brick wall’, and couldn’t break the self incompatibility. We decided to pull the plug, so-to-speak, one year before the end of the project. It was a hard decision to make, but I think we were being honest rather than consuming the remaining financial resources for the sake of completing the project cycle.

- We lost momentum in the project after three years when Margaret Thatcher’s government privatised the PBI, and we had to relocate the project to the university campus in Birmingham (having disposed of the wild potato collection to the CPC as I mentioned earlier). And then build new glasshouse facilities to support the project.

- As the lead investigator, I was not successful in encouraging our postdoc to communicate more readily and openly. That lack of open communication did not help us make the best strategic decisions. And I take responsibility for that. However, on reflection, I think that her appointment to this pioneering project was not the best decision that Alan and I made.

Looking at the progress in diploid breeding since, it’s quite ironic really because several breeders published a call in 2016 to reinvent the potato as a diploid inbred line-based crop, just as we proposed in the 1980s. Our publications have been consistently overlooked.

Inbreeding in diploids became possible because of the discovery of a self compatibility gene, Sli, in the wild species Solanum chacoense after selfing over seven generations. With that breakthrough, such an inbreeding approach had become a reality. Pity that we were not able to break self incompatibility in cultivated diploid potatoes ourselves. And there’s no doubt that advances in molecular genetics and genomics since the 1980s have significantly opened up and advanced this particular breeding strategy.

Around 1988, I was invited by CIP to join three other team members (a program manager, an agronomist, and an economist) to review a seed production project, funded by the SDC [6], in Peru. I believe Ken Brown had suggested me as the seed production technical expert.

L-R: Peruvian agronomist, me, Cesar Vittorelli (CIP review manager), Swiss economist, and Carlos Valverde (program manager and team leader).

I flew to Lima, and we spent the next three weeks visiting sites in La Molina (next to CIP headquarters), in Huancayo in the central Andes, Cuzco in the south of Peru, and Cajamarca in the north.

That consultancy taught me a lot about program reviews and would stand me in good stead later on in my career. Once we had submitted our report, I returned to the UK, and a couple of weeks later spent a few days in Bern at the headquarters of the SDC for a debriefing session.

We found the project had been remarkably successful, making an impact in its operational areas, and we recommended a second phase, which the SDC accepted. Unfortunately, events in Peru overtook the project, as the Shining Path (Sendero Luminoso) guerrilla movement was on the ascendancy and it became too dangerous to move around the country.

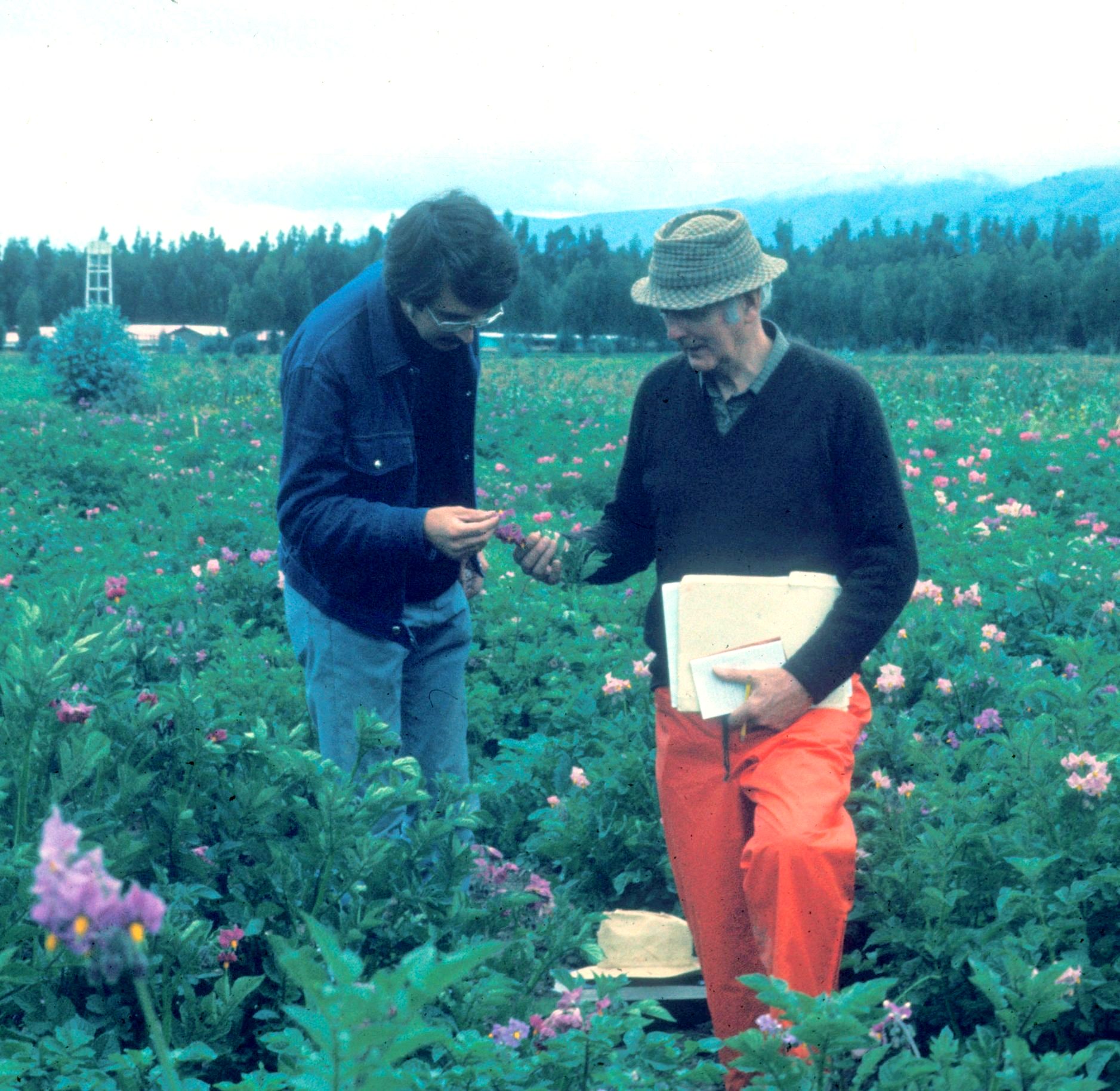

After Jack Hawkes retired in 1982, he and I would meet up for lunch and a beer at least once a week to chat about our common interests in genetic resources conservation, and potatoes in particular. Out of those discussions came a couple of theoretical papers.

The Endosperm Balance Number (or EBN) hypothesis had been proposed to explain the crossability between tuber-bearing Solanum species (there are over 150 wild species of potato). We wrote this paper to combine the taxonomic classification of the different species and their EBNs.

In 1987, Jack asked me to contribute a paper to a symposium he was organizing with Professor David Harris of the Institute of Archaeology at University College London to celebrate the centenary of one of my scientific heroes, Russian geneticist and acclaimed as the Father of Plant Genetic Resources, Nikolai Vavilov. I conceptualized how Vavilov’s Law of Homologous Series could be applied to potatoes.

By the end of the 1990s, I was already looking for scientific pastures new – in rice! And in early 1991, I accepted a position at the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) in the Philippines, and my research focus moved from potatoes to rice.

What surprises me is that some of my potato work endures, and I regularly receive citations of several of my papers, the last of which was published more than 30 years ago.

With the announcement of the International Day of the Potato, it certainly has brought back many memories of the couple of decades I enjoyed working on this fascinating crop.

[1] Hawkes, JG and J Francisco-Ortega (1992). The potato in Spain during the Late 16th Century. Economic Botany 46: 86-97.

[2] Hawkes, JG and J Francisco-Ortega (1993). The early history of the potato in Europe. Euphytica 70: 1-7.

[3] The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) today welcomed the UN’s decision to designate 30 May as International Day of Potato, an opportunity to raise awareness of a crop regularly consumed by billions of people and of global importance for food security and nutrition.

The annual observance was championed by Peru, which submitted a proposal for adoption to the UN General Assembly based on an FAO Conference Resolution of July 7, 2023. The impetus for the Day, which builds upon the International Year of Potato that was observed in 2008, originates from the need to emphasize the significant role of the potato in tackling prevalent global issues, such as food insecurity, poverty and environmental threats.

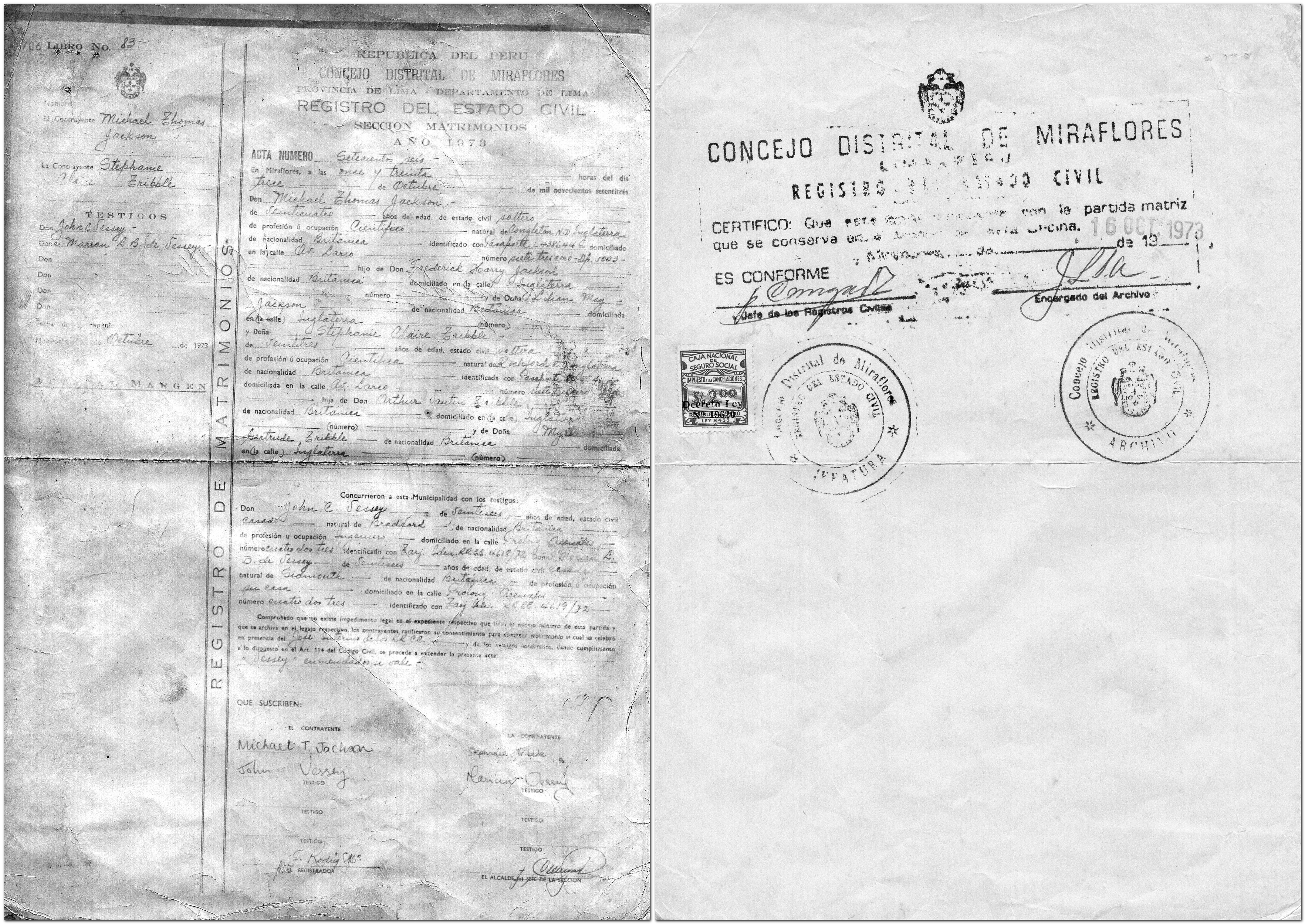

[4] Steph joined me in Lima in July 1973 and we were married there in October. John Vessey and his wife Marian were our witnesses.

In November 1972, a couple of months after she had graduated with an MSc in genetic resources conservation from the University of Birmingham (where we met), Steph joined the Scottish Plant Breeding Station in Edinburgh as Assistant Curator of the Commonwealth Potato Collection. At CIP, she was an Associate Geneticist responsible for the day-to-day management of the institute’s potato germplasm collection.

Steph in one of CIP’s screenhouses at La Molina.

[5] In 1987, we wrote a piece about the somaclone project for the University of Birmingham internal research bulletin. This was picked up by several media, including the BBC and I was invited to appear on a breakfast TV show. Until, that is, the producer realised that the project was a serious piece of research.

[5] In 1987, we wrote a piece about the somaclone project for the University of Birmingham internal research bulletin. This was picked up by several media, including the BBC and I was invited to appear on a breakfast TV show. Until, that is, the producer realised that the project was a serious piece of research.

One of the tabloid newspapers, The Sun, was less forgiving, and ran a brief paragraph on page 3 (Crunch time for boffins) alongside the daily well-endowed young lady. Click on the image to enlarge.

[6] The seed project was my second contact with the SDC (after PRECODEPA). After I joined IRRI in 1991, the SDC funded a five year project from 1995 to rescue rice biodiversity, among other objectives. I have written about that project here.

And, at The University of Birmingham, as the clock on Old Joe (actually the Joseph Chamberlain Memorial Clock Tower) struck 12 noon, so the Chancellor’s Procession made its way (to a musical accompaniment played by the University Organist) from the rear of the Great Hall to the stage.

And, at The University of Birmingham, as the clock on Old Joe (actually the Joseph Chamberlain Memorial Clock Tower) struck 12 noon, so the Chancellor’s Procession made its way (to a musical accompaniment played by the University Organist) from the rear of the Great Hall to the stage. All the graduands and their guests remained seated.

All the graduands and their guests remained seated.

returned to Birmingham from an expedition to collect wild potatoes in Bolivia. He told me about a one-year vacancy from September that same year at the International Potato Center (CIP) in Lima, Peru, and asked if I’d be interested. Not half! And as the saying goes, The rest is history.

returned to Birmingham from an expedition to collect wild potatoes in Bolivia. He told me about a one-year vacancy from September that same year at the International Potato Center (CIP) in Lima, Peru, and asked if I’d be interested. Not half! And as the saying goes, The rest is history.

It was about the

It was about the

Among the species identified in the course of Jack’s dissertation research was Solanum ballsii from northern Argentina, which he dedicated to EK Balls in a formal description in 1944. However, in his 1963 revised taxonomy of the tuber-bearing Solanums (potatoes), Jack (with his Danish colleague Jens Peter Hjerting, 1917-2012) recognized Solanum ballsii simply as a subspecies of Solanum vernei, a species which has since provided many important sources of resistance to the potato cyst nematode.

Among the species identified in the course of Jack’s dissertation research was Solanum ballsii from northern Argentina, which he dedicated to EK Balls in a formal description in 1944. However, in his 1963 revised taxonomy of the tuber-bearing Solanums (potatoes), Jack (with his Danish colleague Jens Peter Hjerting, 1917-2012) recognized Solanum ballsii simply as a subspecies of Solanum vernei, a species which has since provided many important sources of resistance to the potato cyst nematode.

I enjoyed my

I enjoyed my  A third cohort of students arrived in Birmingham in September 1971, among them Stephanie Tribble from Southend-on-Sea who had just graduated from the

A third cohort of students arrived in Birmingham in September 1971, among them Stephanie Tribble from Southend-on-Sea who had just graduated from the

We upended their world when I took the position at IRRI and they moved to the Philippines with Steph just after Christmas 1991. Even more challenging was their enrolment in the

We upended their world when I took the position at IRRI and they moved to the Philippines with Steph just after Christmas 1991. Even more challenging was their enrolment in the  could transfer to

could transfer to

After a gap year, Philippa began her studies in Psychology at

After a gap year, Philippa began her studies in Psychology at

She spent six months looking for a job, finally landing a research assistantship in the

She spent six months looking for a job, finally landing a research assistantship in the

I’d joined the

I’d joined the

In October 1975, I successfully defended my PhD thesis (The evolutionary significance of the triploid cultivated potato, Solanum x chaucha Juz. et Buk.) at the University of Birmingham, where my co-supervisor, potato taxonomist and germplasm pioneer

In October 1975, I successfully defended my PhD thesis (The evolutionary significance of the triploid cultivated potato, Solanum x chaucha Juz. et Buk.) at the University of Birmingham, where my co-supervisor, potato taxonomist and germplasm pioneer During my time in Lima, Dr Roger Rowe (left, then head of CIP’s Breeding and Genetics Department) was my local supervisor.

During my time in Lima, Dr Roger Rowe (left, then head of CIP’s Breeding and Genetics Department) was my local supervisor.

I returned to Lima just before the New Year 1976, knowing that CIP’s Director General,

I returned to Lima just before the New Year 1976, knowing that CIP’s Director General,

Plant pathologist Professor Luis Carlos Gonzalez (right, from the University of Costa Rica in San José) and I also studied how to control the disease through a combination of tolerant varieties and soil and weed management.

Plant pathologist Professor Luis Carlos Gonzalez (right, from the University of Costa Rica in San José) and I also studied how to control the disease through a combination of tolerant varieties and soil and weed management.

In 1977,

In 1977,

I can’t finish this section about my time at CIP without mentioning Dr Ken Brown (left), who was head of Regional Research.

I can’t finish this section about my time at CIP without mentioning Dr Ken Brown (left), who was head of Regional Research.

Because of the

Because of the  In the late 1980s, my colleague Brian Ford-Lloyd (right) and I ran a project, funded by KP Agriculture (and managed by my former CIP colleague, Dr John Vessey) to generate

In the late 1980s, my colleague Brian Ford-Lloyd (right) and I ran a project, funded by KP Agriculture (and managed by my former CIP colleague, Dr John Vessey) to generate

It was surely the influence of one of my mentors,

It was surely the influence of one of my mentors,

Almost immediately after returning to Birmingham, I discovered (by looking through Flora Europaea once again) that the origin of the grasspea, Lathyrus sativus, was unknown. The

Almost immediately after returning to Birmingham, I discovered (by looking through Flora Europaea once again) that the origin of the grasspea, Lathyrus sativus, was unknown. The  The academic year September 1981-September 1982 was my first full year at Birmingham. Among the CUPGR intake was a Malaysian student, Abdul bin Ghani Yunus (right), who asked me to supervise his MSc research project. I persuaded him to tackle a study of variation in the grasspea and its wild relatives, much along the lines I had approached lentil a decade earlier.

The academic year September 1981-September 1982 was my first full year at Birmingham. Among the CUPGR intake was a Malaysian student, Abdul bin Ghani Yunus (right), who asked me to supervise his MSc research project. I persuaded him to tackle a study of variation in the grasspea and its wild relatives, much along the lines I had approached lentil a decade earlier.

I was surprised recently to read a tweet (or whatever they’re now called) on X suggesting that all university lecturers should be required to receive formal teacher training and an appropriate qualification. Just as teachers of schoolchildren must complete the

I was surprised recently to read a tweet (or whatever they’re now called) on X suggesting that all university lecturers should be required to receive formal teacher training and an appropriate qualification. Just as teachers of schoolchildren must complete the  But when I joined the University of Birmingham as a lecturer in the Department of Plant Biology (School of Biological Sciences) in April 1981 there was no such requirement for teacher training, nor do I remember much if any support being provided. You simply got on with it – for better or worse. Furthermore, teaching loads or commitments, or ability never counted much towards promotion prospects. Research (and research income) was the be-all and end-all.

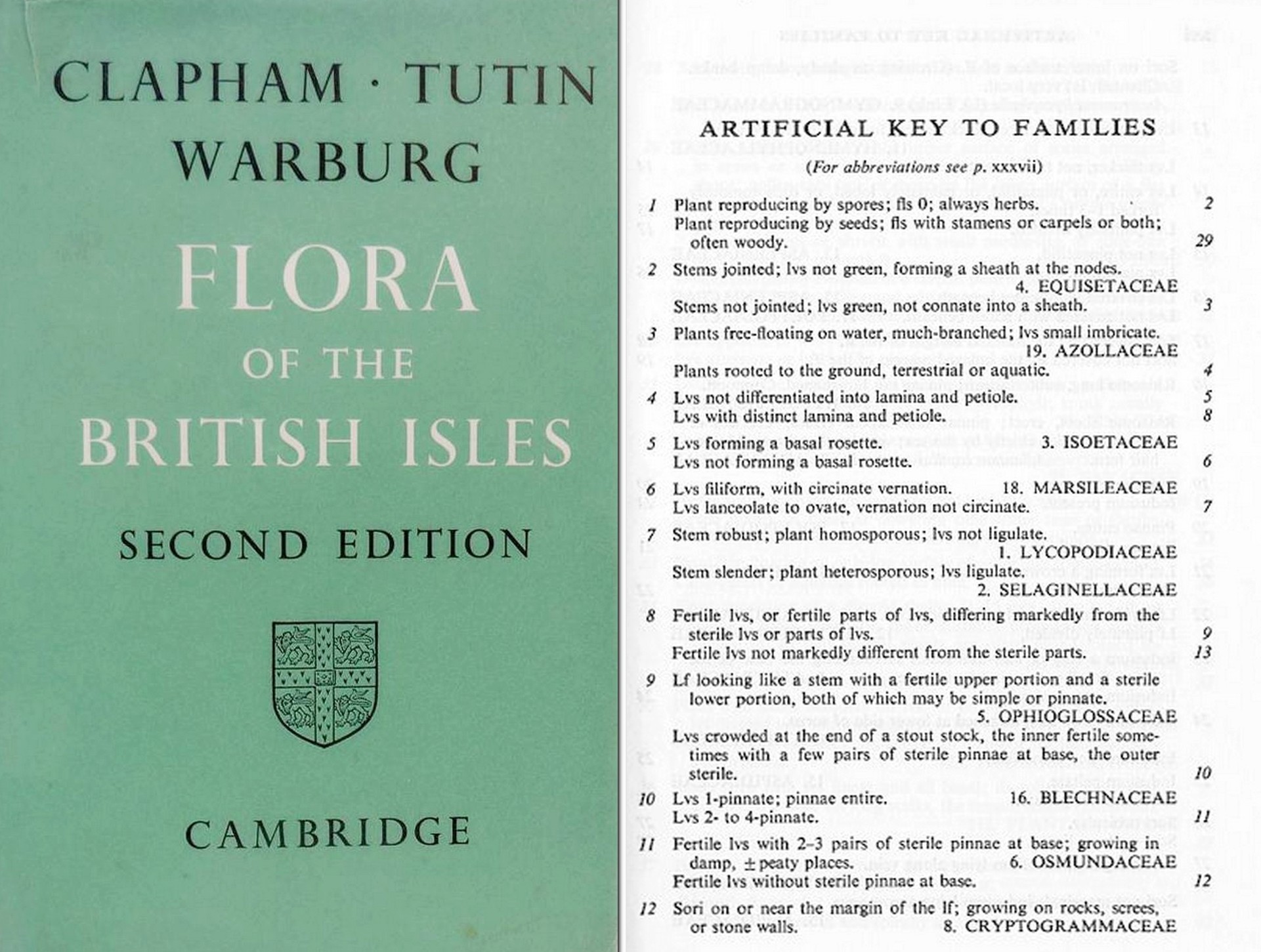

But when I joined the University of Birmingham as a lecturer in the Department of Plant Biology (School of Biological Sciences) in April 1981 there was no such requirement for teacher training, nor do I remember much if any support being provided. You simply got on with it – for better or worse. Furthermore, teaching loads or commitments, or ability never counted much towards promotion prospects. Research (and research income) was the be-all and end-all. Come the beginning of the Summer Term in May however, I found myself facing a group of about 35 second year plant biology students for the first time to teach them some aspects of flowering plant taxonomy (along with my colleague Dr Richard Lester, at right, with whom I didn’t always see eye-to-eye over many aspects of course content and delivery).

Come the beginning of the Summer Term in May however, I found myself facing a group of about 35 second year plant biology students for the first time to teach them some aspects of flowering plant taxonomy (along with my colleague Dr Richard Lester, at right, with whom I didn’t always see eye-to-eye over many aspects of course content and delivery). practical component using a synthetic population made up of many different barley varieties), and a small module on agroecosystems. I also helped my colleague Professor Brian Ford-Lloyd (right) in some aspects of his data management module.

practical component using a synthetic population made up of many different barley varieties), and a small module on agroecosystems. I also helped my colleague Professor Brian Ford-Lloyd (right) in some aspects of his data management module.

John, a plant pathologist working on bacterial diseases of potato, was a colleague of ours at the

John, a plant pathologist working on bacterial diseases of potato, was a colleague of ours at the

It’s by chance, I suppose, that Steph and I got together in the first place. We met at the University of Birmingham, where we studied for our MSc degrees in

It’s by chance, I suppose, that Steph and I got together in the first place. We met at the University of Birmingham, where we studied for our MSc degrees in  But fate stepped in I guess.

But fate stepped in I guess.

While we were allowed to post marriage banns in the British Embassy, we had to announce our intention to marry in the official Peruvian government gazette, El Peruano, and one of the principal daily broadsheets (El Comercio if memory serves me right), and have the police visit us at our apartment to verify our address. I think we also had to have blood tests as well. This all took time, but everything was eventually in place for us to set the wedding date: 13 October.

While we were allowed to post marriage banns in the British Embassy, we had to announce our intention to marry in the official Peruvian government gazette, El Peruano, and one of the principal daily broadsheets (El Comercio if memory serves me right), and have the police visit us at our apartment to verify our address. I think we also had to have blood tests as well. This all took time, but everything was eventually in place for us to set the wedding date: 13 October.

Steph became an enthusiastic beader and has made several hundred pieces of jewelry since then. In Los Baños we had a live-in helper, Lilia, and so in the heat of Los Baños, Steph was spared the drudgery of housework or cooking, and could focus on the hobbies she enjoyed, including a daily swim in the IRRI pool, and looking after her garden and orchids.

Steph became an enthusiastic beader and has made several hundred pieces of jewelry since then. In Los Baños we had a live-in helper, Lilia, and so in the heat of Los Baños, Steph was spared the drudgery of housework or cooking, and could focus on the hobbies she enjoyed, including a daily swim in the IRRI pool, and looking after her garden and orchids.

By 1976, Steph and I had moved to Costa Rica, where I was CIP’s regional leader for Mexico, Central America, and the Caribbean. In early 1980, I was returning from a trip to the Dominican Republic, and transiting overnight in Miami. Joining one of the (interminable) immigration queues, I looked over to my right and, lo and behold to my surprise, Dave was just a couple of passengers ahead of me in the parallel queue. He had just flown in from the UK, on his way to Bolivia, his second expedition there. He had a connecting flight, and once we were both through immigration we only had about 15 minutes to chat before he had to find his boarding gate. What a coincidence!

By 1976, Steph and I had moved to Costa Rica, where I was CIP’s regional leader for Mexico, Central America, and the Caribbean. In early 1980, I was returning from a trip to the Dominican Republic, and transiting overnight in Miami. Joining one of the (interminable) immigration queues, I looked over to my right and, lo and behold to my surprise, Dave was just a couple of passengers ahead of me in the parallel queue. He had just flown in from the UK, on his way to Bolivia, his second expedition there. He had a connecting flight, and once we were both through immigration we only had about 15 minutes to chat before he had to find his boarding gate. What a coincidence!

However, by 1990, Trevor had left IBPGR and was working out of Washington, DC, helping to set up the International Network for Bamboo and Rattan (INBAR, now the

However, by 1990, Trevor had left IBPGR and was working out of Washington, DC, helping to set up the International Network for Bamboo and Rattan (INBAR, now the

As an Associate Taxonomist at CIP I had two responsibilities:

As an Associate Taxonomist at CIP I had two responsibilities:

project as I did, or to travel throughout such an awe-inspiring country. I continue to count my blessings.

project as I did, or to travel throughout such an awe-inspiring country. I continue to count my blessings.

I co-taught a BSc third (final) year module on genetic resources with my close friend and colleague Brian Ford-Lloyd (left), and contributed half the lectures in a second-year module on flowering plant taxonomy with another colleague, Richard Lester. Fortunately I had no first year teaching.

I co-taught a BSc third (final) year module on genetic resources with my close friend and colleague Brian Ford-Lloyd (left), and contributed half the lectures in a second-year module on flowering plant taxonomy with another colleague, Richard Lester. Fortunately I had no first year teaching. Around 1988, the four departments (Plant Biology, Zoology and Comparative Physiology, Microbiology, and Genetics) making up the School of Biological Sciences merged, and formed five research groups. I moved to the Plant Genetics Group, and was quite contented working with my new head of group, Professor Mike Kearsey (left above). Much better than the head of Plant Biology,

Around 1988, the four departments (Plant Biology, Zoology and Comparative Physiology, Microbiology, and Genetics) making up the School of Biological Sciences merged, and formed five research groups. I moved to the Plant Genetics Group, and was quite contented working with my new head of group, Professor Mike Kearsey (left above). Much better than the head of Plant Biology,  Gatwick to Manila via Hong Kong was delayed more than 12 hours. Instead of arriving in Los Baños a day ahead of the interviews, I arrived in the early hours of the morning and managed about two hours sleep before I had a breakfast meeting with the Director General, Klaus Lampe (right) and his three deputies! The interview sessions lasted more than three days. There were two other candidates, friends of mine who had studied at Birmingham under Jack Hawkes!

Gatwick to Manila via Hong Kong was delayed more than 12 hours. Instead of arriving in Los Baños a day ahead of the interviews, I arrived in the early hours of the morning and managed about two hours sleep before I had a breakfast meeting with the Director General, Klaus Lampe (right) and his three deputies! The interview sessions lasted more than three days. There were two other candidates, friends of mine who had studied at Birmingham under Jack Hawkes! In 1995 we initiated a

In 1995 we initiated a

Then, quite out of the blue at the beginning of January 2001, Director General Ron Cantrell (right) asked me to stop by his office. He proposed I should leave GRC and join the senior management team as a Director to reorganize and manage the institute’s research portfolio and relationships with the donor community. I said I’d think it over, talk with Steph, and give him my answer in a couple of days.

Then, quite out of the blue at the beginning of January 2001, Director General Ron Cantrell (right) asked me to stop by his office. He proposed I should leave GRC and join the senior management team as a Director to reorganize and manage the institute’s research portfolio and relationships with the donor community. I said I’d think it over, talk with Steph, and give him my answer in a couple of days.

But all good things come to an end, and by 2009 I’d already decided that I wanted to retire (and smell the roses, as they say), even though Zeigler encouraged me to stay on. By then I was already planning the celebrations for IRRI’s 50th anniversary, and agreed to see those through to April 2010. What fun we had, at the

But all good things come to an end, and by 2009 I’d already decided that I wanted to retire (and smell the roses, as they say), even though Zeigler encouraged me to stay on. By then I was already planning the celebrations for IRRI’s 50th anniversary, and agreed to see those through to April 2010. What fun we had, at the

This is the latest estimate of the world’s population announced by the United Nations on

This is the latest estimate of the world’s population announced by the United Nations on  Sustainable food and agricultural production were appropriately important themes at the latest climate change conference—

Sustainable food and agricultural production were appropriately important themes at the latest climate change conference—

My first encounter with plant breeding—or plant breeders for that matter—was during a visit, in July 1969, to the

My first encounter with plant breeding—or plant breeders for that matter—was during a visit, in July 1969, to the  It was in that course that I was introduced to one of the classic texts on the topic, Principles of Plant Breeding by University of California-Davis geneticist,

It was in that course that I was introduced to one of the classic texts on the topic, Principles of Plant Breeding by University of California-Davis geneticist,

To date, the impact of genetic engineering in crop improvement has not been as significant as the technology promised, primarily because of opposition (environmental, social, and political) to the deployment of genetically-modified varieties. I

To date, the impact of genetic engineering in crop improvement has not been as significant as the technology promised, primarily because of opposition (environmental, social, and political) to the deployment of genetically-modified varieties. I  But here’s another challenge that was first raised some years back by one of my former colleagues at IRRI, Melissa Fitzgerald (right) who was formerly head of the Grain Quality, Nutrition, and Postharvest Center, and is now Professor and Interim Head of the School of Agriculture and Food Sciences at the University of Queensland, Australia.

But here’s another challenge that was first raised some years back by one of my former colleagues at IRRI, Melissa Fitzgerald (right) who was formerly head of the Grain Quality, Nutrition, and Postharvest Center, and is now Professor and Interim Head of the School of Agriculture and Food Sciences at the University of Queensland, Australia. It all started on this day, 50 years ago, when I joined the

It all started on this day, 50 years ago, when I joined the  In May 1971 there was a significant development in terms of long-term funding for agricultural research with the setting up of the

In May 1971 there was a significant development in terms of long-term funding for agricultural research with the setting up of the

For the first three years, my work was supervised and generously supported by an American geneticist, Dr Roger Rowe (right, with his wife Norma) who joined CIP on 1 May 1973 as head of the Breeding and Genetics Department. I owe a great deal to Roger who has remained a good friend all these years.

For the first three years, my work was supervised and generously supported by an American geneticist, Dr Roger Rowe (right, with his wife Norma) who joined CIP on 1 May 1973 as head of the Breeding and Genetics Department. I owe a great deal to Roger who has remained a good friend all these years. Jim Bryan

Jim Bryan In April 1981, I joined the University of Birmingham as a Lecturer in the Department of Plant Biology (as the Department of Botany had been renamed since I graduated).

In April 1981, I joined the University of Birmingham as a Lecturer in the Department of Plant Biology (as the Department of Botany had been renamed since I graduated).

And so I successfully applied for the position of Head of the Genetic Resources Center at IRRI, and once again working under the CGIAR umbrella. I moved to the Philippines in July, and stayed there for the next 19 years until retiring at the end of April 2010.

And so I successfully applied for the position of Head of the Genetic Resources Center at IRRI, and once again working under the CGIAR umbrella. I moved to the Philippines in July, and stayed there for the next 19 years until retiring at the end of April 2010. With responsibility for the world’s largest and most important

With responsibility for the world’s largest and most important  My closest friend and colleague at IRRI was fellow Brit and crop modeller,

My closest friend and colleague at IRRI was fellow Brit and crop modeller,

To most people the word ‘conservation’ conjures up visions of lovable cuddly animals like giant pandas on the verge of extinction. Or it refers to the prevention of the mass slaughter of endangered whale species, under threat because of human’s greed or short-sightedness. Comparatively few people however, are moved to action or financial contribution by the idea of economically important plant species disappearing from the face of the earth. Precious orchids with undoubted aesthetic appeal, or the vegetation of the Amazonian rain forest, where sheer vastness cannot fail to impress, may attract deserved attention. But plant genetic resources [or plant biodiversity as a whole, I would hasten to add] make little impression on the heart even though their disappearance could herald famine on a greater scale than ever seen before, leading to ultimate world-wide disaster.

To most people the word ‘conservation’ conjures up visions of lovable cuddly animals like giant pandas on the verge of extinction. Or it refers to the prevention of the mass slaughter of endangered whale species, under threat because of human’s greed or short-sightedness. Comparatively few people however, are moved to action or financial contribution by the idea of economically important plant species disappearing from the face of the earth. Precious orchids with undoubted aesthetic appeal, or the vegetation of the Amazonian rain forest, where sheer vastness cannot fail to impress, may attract deserved attention. But plant genetic resources [or plant biodiversity as a whole, I would hasten to add] make little impression on the heart even though their disappearance could herald famine on a greater scale than ever seen before, leading to ultimate world-wide disaster. For many years, the

For many years, the

My best friend Alan Brennan, a year younger than me, lived just a few doors further up Moody Street. But we didn’t go to the same school. I was enrolled at Mossley C of E village school, a couple of miles south of the town, like my two brothers and sister before me. Each weekday morning, my elder brother Edgar (just over two years older than me) and I took the bus together from the High Street to Mossley. Sometimes, in the summer, I’d walk home on my own (something that parents wouldn’t even contemplate today).

My best friend Alan Brennan, a year younger than me, lived just a few doors further up Moody Street. But we didn’t go to the same school. I was enrolled at Mossley C of E village school, a couple of miles south of the town, like my two brothers and sister before me. Each weekday morning, my elder brother Edgar (just over two years older than me) and I took the bus together from the High Street to Mossley. Sometimes, in the summer, I’d walk home on my own (something that parents wouldn’t even contemplate today).

However, by the end of 2019 we had eventually decided to leave Bromsgrove and move north to Newcastle upon Tyne where our younger daughter Philippa and her family live. (Our elder daughter lives in Minnesota).

However, by the end of 2019 we had eventually decided to leave Bromsgrove and move north to Newcastle upon Tyne where our younger daughter Philippa and her family live. (Our elder daughter lives in Minnesota).

years ago today (Friday 17 December 1971) I received my MSc degree in Conservation and Utilization of Plant Genetic Resources from the University of Birmingham. Half a century!

years ago today (Friday 17 December 1971) I received my MSc degree in Conservation and Utilization of Plant Genetic Resources from the University of Birmingham. Half a century!

One milestone for Brian and me was the publication, in 1986, of our introductory text on plant genetic resources, one of the first books in this field, and which sold out within 18 months. It’s still available as a digital print on demand publication from Cambridge University Press.

One milestone for Brian and me was the publication, in 1986, of our introductory text on plant genetic resources, one of the first books in this field, and which sold out within 18 months. It’s still available as a digital print on demand publication from Cambridge University Press.

I’ve often been asked how hard it was to resign from a tenured position at the university. Not very hard at all. Even though I was about to be promoted to Senior Lecturer. But the lure of resuming my career in the

I’ve often been asked how hard it was to resign from a tenured position at the university. Not very hard at all. Even though I was about to be promoted to Senior Lecturer. But the lure of resuming my career in the

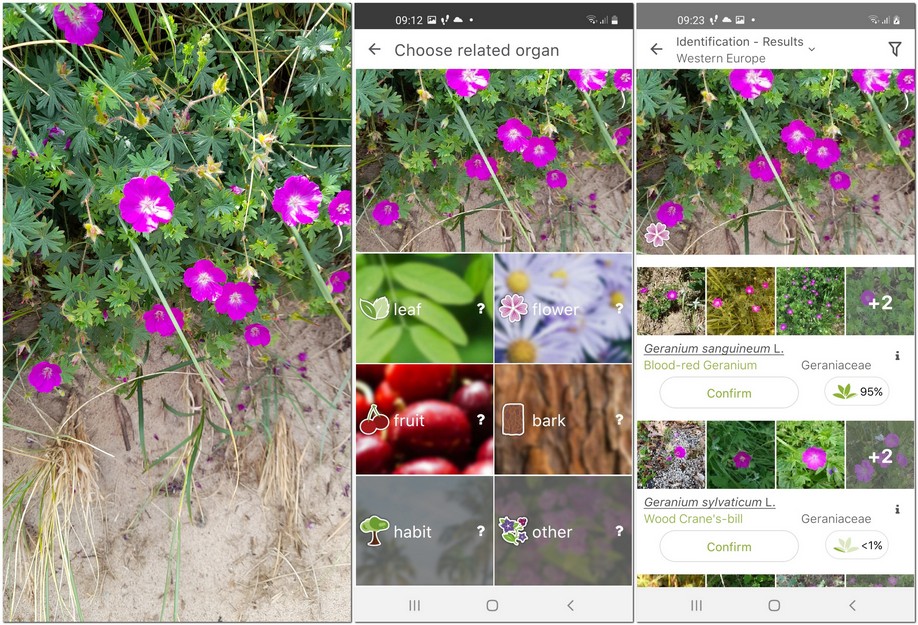

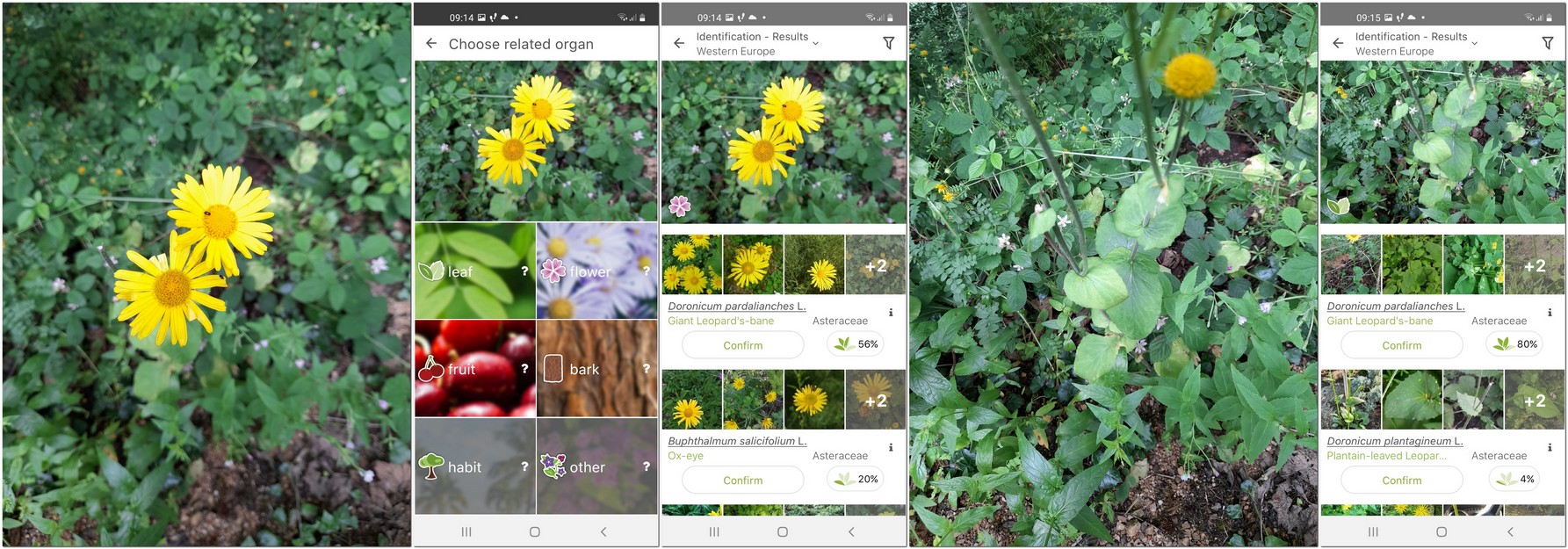

So what is Pl@ntNet? On its website, it states that Pl@ntNet is a citizen science project available as an app that helps you identify plants thanks to your pictures. This project is part of the Floris’Tic initiative, which aims to promote scientific, technical and industrial culture in plant sciences. For this, it relies on a consortium of complementary expertise in Botany, IT and Project Animation.

So what is Pl@ntNet? On its website, it states that Pl@ntNet is a citizen science project available as an app that helps you identify plants thanks to your pictures. This project is part of the Floris’Tic initiative, which aims to promote scientific, technical and industrial culture in plant sciences. For this, it relies on a consortium of complementary expertise in Botany, IT and Project Animation. Pl@ntNet is a French project under the

Pl@ntNet is a French project under the

28 June 1991. It was a Friday. Ten years and three months since I joined the University of Birmingham as a Lecturer in Plant Biology. And it was my last day in that post. A brief farewell party in the School of Biological Sciences at the end of the day, and that was it. I was no longer an academic.

28 June 1991. It was a Friday. Ten years and three months since I joined the University of Birmingham as a Lecturer in Plant Biology. And it was my last day in that post. A brief farewell party in the School of Biological Sciences at the end of the day, and that was it. I was no longer an academic. Philippines with just under 24 hours to recover from my trip before the interview schedule began. In the end, I had less than four hours sleep, and was up for a 7 am breakfast meeting with Director General

Philippines with just under 24 hours to recover from my trip before the interview schedule began. In the end, I had less than four hours sleep, and was up for a 7 am breakfast meeting with Director General  Even so, Lampe asked me to represent IRRI at a genetic resources meeting held in April at the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) in Rome. That would be the first of many meetings at FAO and even more visits to Rome where the International Plant Genetic Resources Institute (IPGRI, now Bioversity International) also had its office.

Even so, Lampe asked me to represent IRRI at a genetic resources meeting held in April at the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) in Rome. That would be the first of many meetings at FAO and even more visits to Rome where the International Plant Genetic Resources Institute (IPGRI, now Bioversity International) also had its office. I don’t remember too much about the trip from that point. Not because of over-imbibing, I hasten to add. It was just uneventful. On arrival in Manila, I was greeted by Director of Administration Tim Bertotti (right) and his Vietnamese wife who would be my ‘welcomers’ for the next few weeks, show me the IRRI ropes, so to speak, and be a couple I could turn to for advice. Having collected my heavy bags, and found the IRRI driver we headed south to Los Baños, where I stayed in the IRRI Guesthouse for the next month or so until the house allocated to me had been redecorated.

I don’t remember too much about the trip from that point. Not because of over-imbibing, I hasten to add. It was just uneventful. On arrival in Manila, I was greeted by Director of Administration Tim Bertotti (right) and his Vietnamese wife who would be my ‘welcomers’ for the next few weeks, show me the IRRI ropes, so to speak, and be a couple I could turn to for advice. Having collected my heavy bags, and found the IRRI driver we headed south to Los Baños, where I stayed in the IRRI Guesthouse for the next month or so until the house allocated to me had been redecorated.

I worked overseas for much of my career—just over 27 years—in three countries. For those who are new to my blog, I’m from the UK, and I worked in agricultural research (on potatoes and rice) in Peru, Costa Rica, and the Philippines, besides spending a decade in the UK in between teaching plant sciences at the University of Birmingham.

I worked overseas for much of my career—just over 27 years—in three countries. For those who are new to my blog, I’m from the UK, and I worked in agricultural research (on potatoes and rice) in Peru, Costa Rica, and the Philippines, besides spending a decade in the UK in between teaching plant sciences at the University of Birmingham. I won’t deny that I have a particular soft-spot for Peru. It was a country I’d wanted to visit since I was a small boy, when I often spent hours poring over maps of South America, imagining what those distant countries and cities would be like to visit.

I won’t deny that I have a particular soft-spot for Peru. It was a country I’d wanted to visit since I was a small boy, when I often spent hours poring over maps of South America, imagining what those distant countries and cities would be like to visit.

But, after three years, it was time to move on, and that’s when we began a new chapter in Costa Rica from April 1976 a new chapter. Professionally, for me it was a significant move. I’d turned 27 a few months earlier. CIP’s Director General

But, after three years, it was time to move on, and that’s when we began a new chapter in Costa Rica from April 1976 a new chapter. Professionally, for me it was a significant move. I’d turned 27 a few months earlier. CIP’s Director General