Saturday 13 October 1973, 11:30 am

Lima, Peru

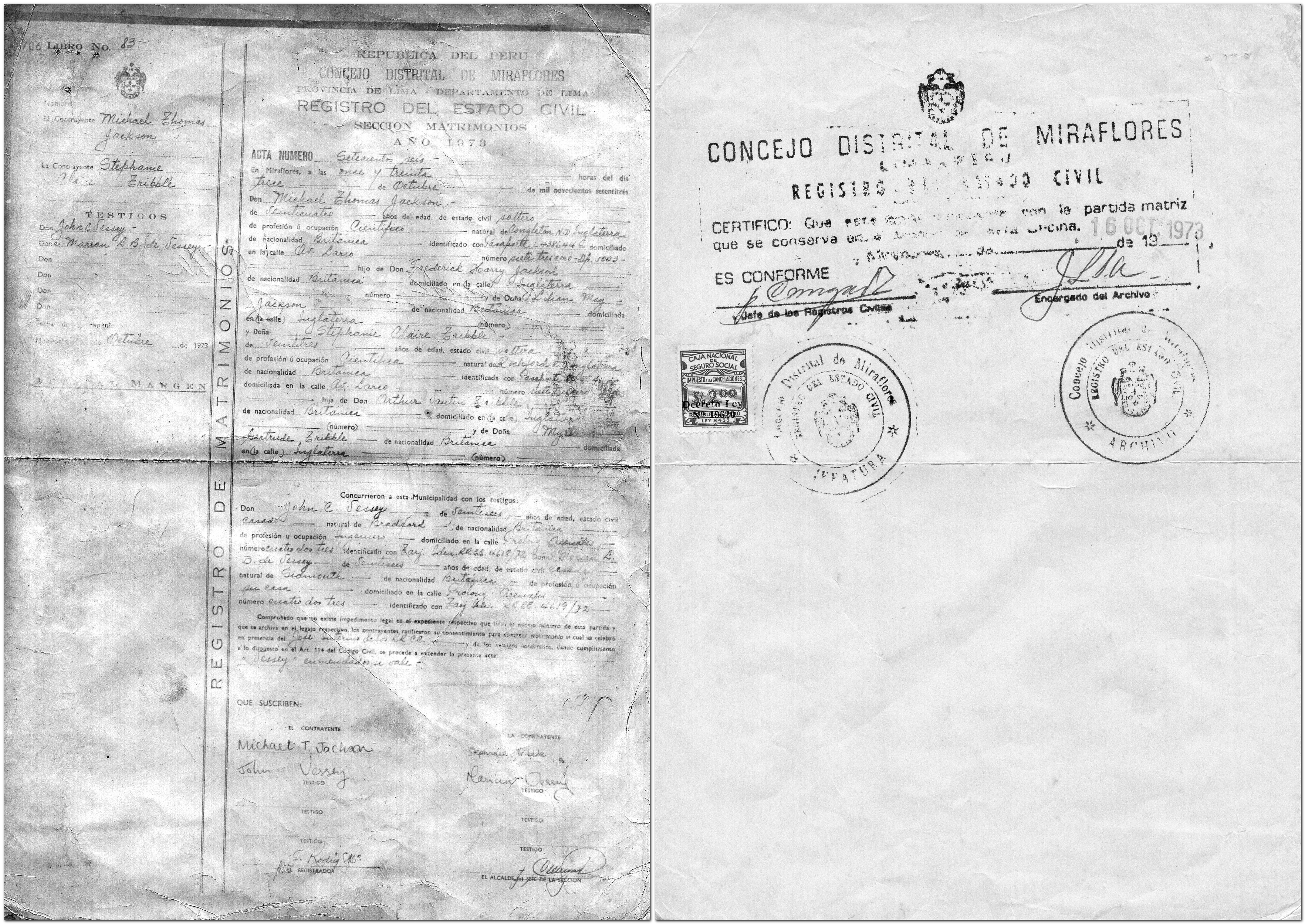

Fifty years ago today, Steph and I were married at the town hall (municipalidad) in the Miraflores district of Lima, where we had an apartment on Avenida José Larco. Steph had turned 24 just five days earlier; it would be my 25th in the middle of November.

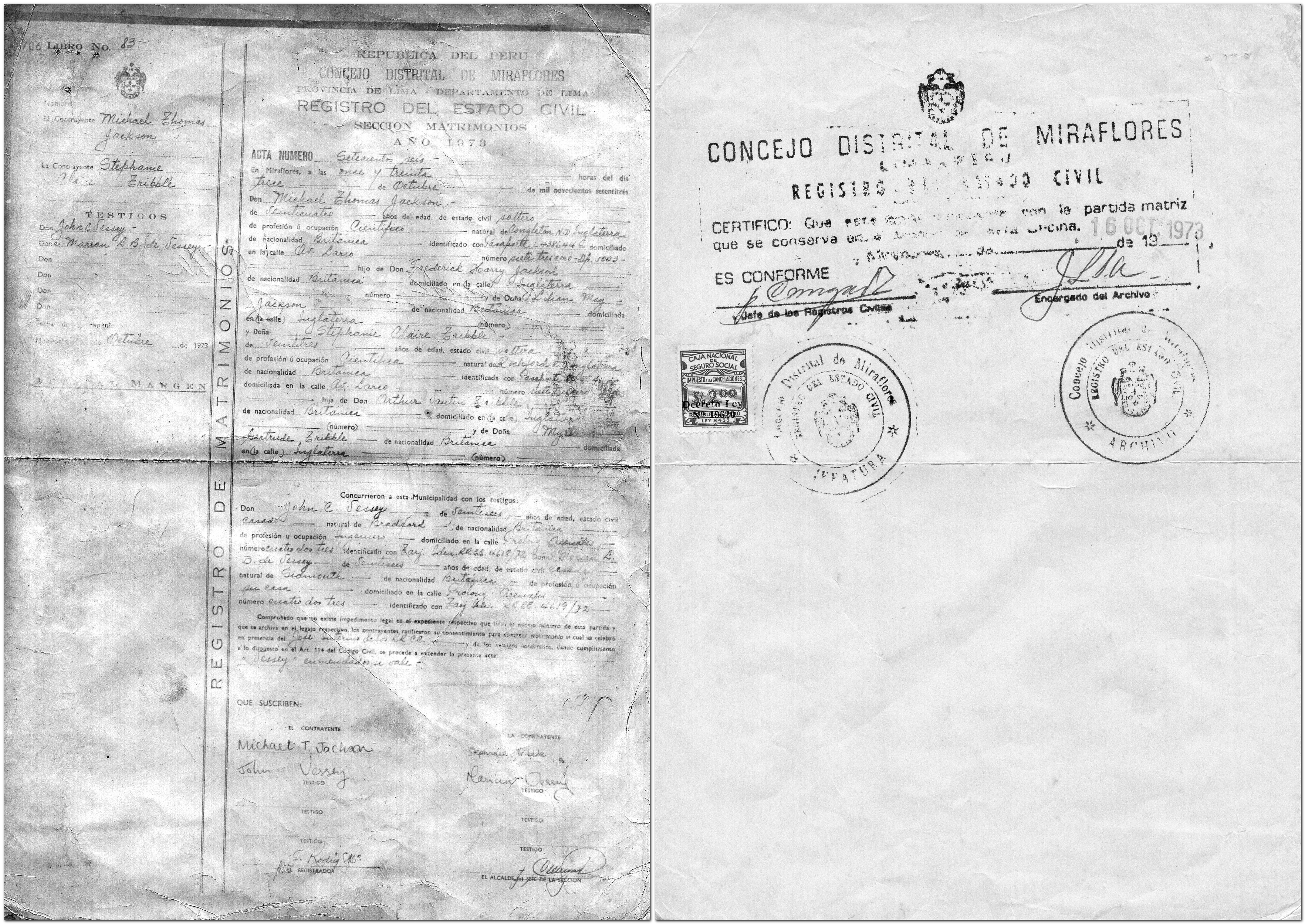

Municipalidad de Miraflores, Lima

It was a brief ceremony, lasting 15 minutes at most, and a quiet affair. Just Steph and me, and our two witnesses, John and Marian Vessey. And the mayor (or other official) of course.

John, a plant pathologist working on bacterial diseases of potato, was a colleague of ours at the International Potato Center (CIP) in Lima, who had joined the center a few months before I arrived in Lima in January 1973.

John, a plant pathologist working on bacterial diseases of potato, was a colleague of ours at the International Potato Center (CIP) in Lima, who had joined the center a few months before I arrived in Lima in January 1973.

Enjoying pre-lunch drinks with Marian and John at ‘La Granja Azul‘ restaurant at Santa Clara – Ate, on the outskirts of Lima.

The newly-weds.

It’s by chance, I suppose, that Steph and I got together in the first place. We met at the University of Birmingham, where we studied for our MSc degrees in Conservation and Utilization of Plant Genetic Resources.

It’s by chance, I suppose, that Steph and I got together in the first place. We met at the University of Birmingham, where we studied for our MSc degrees in Conservation and Utilization of Plant Genetic Resources.

Steph arrived in Birmingham in September 1971, just after I had finished the one-year course. I was expecting imminently to head off to Peru where I had been offered a position at CIP to help curate the large collection of native potato varieties in the CIP genebank. So, had I flown off to South America then, our paths would have hardly crossed.

But fate stepped in I guess.

But fate stepped in I guess.

My departure to Peru was delayed until January 1973. So I registered for a PhD with renowned potato expert Professor Jack Hawkes (right, head of the Department of Botany and architect of the MSc course), and began my research in Birmingham while CIP’s Director General, Richard Sawyer, negotiated a financial package from the British government to support the center’s research for development agenda, and my work there in particular.

It must have been early summer 1972 that Steph and I first got together. Having completed the MSc written exams in May, Steph began a research project on reproductive strategies in three legume species, directed by Dr Trevor Williams (who had supervised my project a year earlier on lentils). And she completed the course in September.

By then, she had successfully applied for a scientific officer position at the Scottish Plant Breeding Station in Edinburgh (SPBS, now part—after several interim phases—of the James Hutton Institute in Dundee), as Assistant Curator of the Commonwealth Potato Collection. But that position wasn’t due to start until November.

Our VW Variant in Peru, around May 1973 – before receiving a Peruvian registration plate.

In early November I took delivery of a left-hand-drive Volkswagen for shipment to Peru. On a rather dismal Birmingham morning, we loaded up the VW with Steph’s belongings and headed north to Edinburgh. She returned to Birmingham in mid-December for her graduation.

Then, just after Christmas 1972, we met up in a London for a couple of days before I was due to fly out to Lima.

At that time we could not make any firm commitments although we knew that—given the opportunity—we wanted to be together.

Again fate stepped in. On 4 January 1973, Jack Hawkes and I flew to Lima. Jack had been asked to organize a planning conference to guide CIP’s program to collect and conserve native Andean potato varieties and their wild relatives.

Potato varieties from the Andes of Peru.

While I stayed in a small hotel (the Pensión Beech, in the San Isidro district) until I could find an apartment to rent, Jack stayed with Richard Sawyer and his wife Norma. And it was over dinner one evening that Jack mentioned to Richard that I had a ‘significant other’ in the UK, also working on potato genetic resources, and was there a possibility of finding a position at CIP for her. Richard mulled the idea over, and quickly reached a decision: he offered Steph a position in the Breeding and Genetics Department to work with the germplasm collection.

With that, Steph resigned from the SPBS and made plans to move to Lima in July, with us planning to get married later on in the year.

In the CIP germplasm screenhouses in La Molina. Bottom: with Peruvian potato expert Ing. Carlos Ochoa.

A couple of weeks after I arrived in Peru, I found an apartment in Miraflores at 156 Los Pinos (how that whole area has changed in the intervening 50 years), and that’s where Steph joined me.

In our Los Pinos apartment, Miraflores in July 1973.

A few weeks later we found a larger apartment, nearby at 730 Avda. Larco, apartment 1003. Very interesting during earthquakes!

Around mid-August 1973 we began the paperwork (all those tramites!) to marry in Peru. Not as simple as you might think, but on reflection perhaps not as difficult as we anticipated.

While we were allowed to post marriage banns in the British Embassy, we had to announce our intention to marry in the official Peruvian government gazette, El Peruano, and one of the principal daily broadsheets (El Comercio if memory serves me right), and have the police visit us at our apartment to verify our address. I think we also had to have blood tests as well. This all took time, but everything was eventually in place for us to set the wedding date: 13 October.

While we were allowed to post marriage banns in the British Embassy, we had to announce our intention to marry in the official Peruvian government gazette, El Peruano, and one of the principal daily broadsheets (El Comercio if memory serves me right), and have the police visit us at our apartment to verify our address. I think we also had to have blood tests as well. This all took time, but everything was eventually in place for us to set the wedding date: 13 October.

Some friends wanted to give us a big wedding, but Steph said she just wanted an intimate, quiet day. So that’s what we organized.

In the week leading up to our wedding, we had to present all the notarised documents at the municipality. After the ceremony, we signed the registry, hand-written in enormous volumes (or tomos). There was a bank of clerical staff, all with their Parker fountain pens, inscribing the details of each wedding in their respective tomo. A week later we collected our Constancia de Matrimonio (with some errors) which detailed in which tomo (No. 83, page 706) our marriage had been recorded, as well as photocopies (now sadly faded) of the actual page.

My work, collecting potatoes, took me all over the Andes; not so much for Steph who only made visits every other week or so to CIP’s highland experiment station (at over 3000 masl) in Huancayo east of Lima, and a six hour drive away.

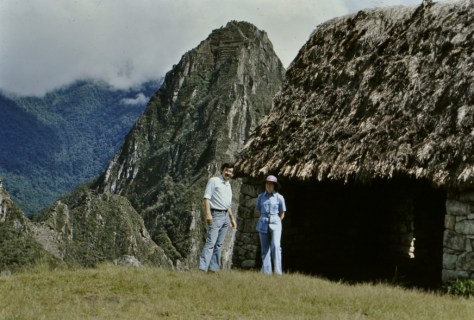

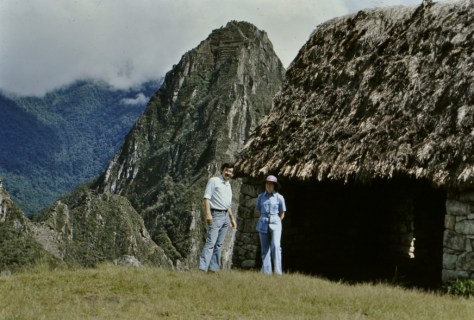

However, Steph and I explored Peru together as much as we could, taking our VW on several long trips, to the north and central Andes, and south to Lake Titicaca. We also delayed our honeymoon until December 1973, flying to Cusco for a few days, and spending one night at Machu Picchu.

At Machu Picchu, December 1973.

In May 1975, we returned to the UK for seven months for me to complete my PhD, returning to Lima just before New Year.

With Jack Hakes and Trevor Williams at my PhD graduation on 12 December 1975 at the University of Birmingham.

Christmas Day 1976 in Turrialba.

Then, in April 1976, we moved to Costa Rica where I worked on potato diseases and production, based in Turrialba, some 70 km east of the capital city, San José. Under the terms of our visas, Steph was not permitted to work in Costa Rica. I became regional representative for CIP’s Region II (Mexico, Central America, and the Caribbean) in August 1997 when my colleague, Oscar Hidalgo (who was based in Toluca, Mexico) headed to North Carolina to begin his PhD studies.

Our elder daughter Hannah Louise was born in San José in April 1978. Later that year, we took our first home leave in the UK and both sets of grandparents were delighted to meet their first granddaughter.

24 April 1978 in the Clinica Santa Rita, San José, Costa Rica.

On home leave in the UK in September 1978.

With Steph’s parents Myrtle and Arthur (top) in Southend-on-Sea, and mine, Lilian and Fred, in Leek.

We spent five happy years in Costa Rica before moving back to Lima at the end of November 1980, and began making plans to move to the Philippines by Easter 1981.

However, in early 1981, a lectureship was created at the University of Birmingham, in the Department of Plant Biology (formerly Botany, where Steph and I had studied), for which I successfully applied. We left CIP at the end of March and had set up home in Bromsgrove (about 13 miles south of Birmingham in north Worcestershire) by the beginning of July.

4 Davenport Drive

A decade after we were married, we were already a family of four. In May 1982 Philippa Alice was born in Bromsgrove.

30 May 1982 in Bromsgrove hospital.

During the 1980s we enjoyed many family holidays, including this one in 1983 on the canals close to home.

Many other family holidays followed, in South Wales, in Norfolk, on the North York Moors, and in 1989, in the Canary Islands.

In Tenerife, Canary Islands in July 1989. Steph is carrying the binoculars that I bought around 1964 and which I still possess.

Hannah (left) and Philippa (right) thrived at local Finstall First School, shown here on their first day of school in 1983 and 1987, respectively.

My work at Birmingham kept me very busy (perhaps too busy), but I particularly enjoyed working with my graduate students (many of them from overseas), and my undergraduate tutees.

All in all, it looked like Birmingham would be a job for life. That was not to be, however. By the end of the 1980s, academic life had sadly lost much of its allure, thanks in no small part to the policies and actions of the Thatcher government. We moved on.

By 1993, we had already been in the Philippines for almost two years, where I had been hired (from July 1991) as head of the Genetic Resources Center (GRC) at the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) in Los Baños, some 65 km south of Manila in the Philippines. I moved there ahead of Steph and the girls (then aged 13 and nine) who joined me just after Christmas 1991.

Meeting fellow newcomer and head of communications, Ted Hutchcroft and his wife at our joint IRRI welcoming party in early 1992.

In 1993 I learned to scuba dive, a year after Hannah, and it was one of the best things I’ve ever done. Philippa trained a couple of years later.

Getting ready to dive, at Arthur’s Place, Anilao, Philippines in January 2003.

Steph was quite content simply to snorkel or beachcomb, and we derived great pleasure from our weekends away (about eight or nine a year) at Anilao, 92 km south from Los Baños. In fact, our weekends in Anilao were one of our greatest enjoyments during the 19 years we spent in the Philippines.

Steph became an enthusiastic beader and has made several hundred pieces of jewelry since then. In Los Baños we had a live-in helper, Lilia, and so in the heat of Los Baños, Steph was spared the drudgery of housework or cooking, and could focus on the hobbies she enjoyed, including a daily swim in the IRRI pool, and looking after her garden and orchids.

Steph became an enthusiastic beader and has made several hundred pieces of jewelry since then. In Los Baños we had a live-in helper, Lilia, and so in the heat of Los Baños, Steph was spared the drudgery of housework or cooking, and could focus on the hobbies she enjoyed, including a daily swim in the IRRI pool, and looking after her garden and orchids.

Steph and Lilia on our last day in IRRI Staff Housing #15 on 30 April 2010.

Hannah and Philippa completed their school education at the International School Manila (ISM) in 1995 and 1999 respectively, both passing the International Baccalaureate Diploma with commendably high scores.

Graduation at ISM: Hannah and Philippa with their friends from around the world.

Traveling to Manila each day from Los Baños had not been an easy journey, due to continual roadworks and indescribable traffic. It was at least two hours each way. By the time Philippa finished school in 1999, the buses were leaving Los Baños at 04:30 in order to reach Manila by the start of classes at 07:15.

In October 1996, Hannah started her university degree in psychology and social anthropology at Swansea University in the UK. However, after two years, she transferred to Macalester College, a highly-rated liberal arts college in St Paul, Minnesota, graduating summa cum laude in psychology and anthropology in May 2000. She then registered for a PhD in industrial and organizational psychology at the University of Minnesota. Philippa began her BSc degree in psychology at the prestigious University of Durham, UK later that same year, in October.

Hannah’s graduation in May 2000 at Macalester College, with Philippa and Michael (Hannah’s boyfriend, now her husband).

Once Hannah and Philippa had left for university, IRRI paid for return visits each year, especially at Christmas.

Christmas 2001. Michael joined Hannah for the visit.

While my work took me outside the Philippines quite often, Steph and I did manage holidays together in Hong Kong/Macau and Australia. And, together with Philippa, we toured Angkor Wat in Cambodia in December 2000.

But Steph also accompanied me on work trips to Laos, Bali, and Japan. She also joined me and my staff when we visited the rice terraces in northern Luzon in March 2009.

Enjoying a cold beer as the sun goes down, near Sagada, northern Luzon, Philippines.

Overlooking the Batad rice terraces in northern Luzon in March 2009.

However, we always used our annual home leave allowance to return to the UK, stay in our home in Bromsgrove (which we had purposely left unoccupied), and meet up with family and friends.

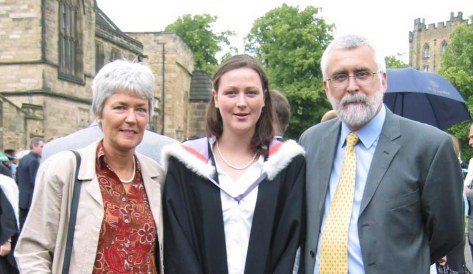

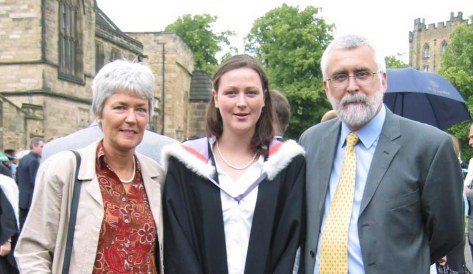

Philippa was awarded a 2:1 degree in July 2003, and the graduation ceremony took place inside Durham Cathedral. She then headed off to Vancouver for a year, before returning to the UK and looking for a job, eventually settling in Newcastle upon Tyne where she has lived ever since.

Outside Durham Cathedral where Phil received her BSc degree from the university’s Chancellor, the late Sir Peter Ustinov.

Hannah married Michael in May 2006, and finished her PhD. We flew to Minnesota from the Philippines.

15 May 2006, at the Marjorie McNeely Conservatory in Como Park, St Paul.

PhD graduation at the University of Minnesota.

Philippa registered for a PhD in biological psychology at Northumbria University in Newcastle upon Tyne where she was already working.

Professionally, the period between 2001 and my retirement in 2010 was the most satisfying. I had changed positions at IRRI in May, moving from GRC to join the institute’s senior management team as Director for Program Planning and Communications (DPPC). I worked with a great team, and we really made an impact to increase donor support for IRRI’s research program. However, by 2008/9 when my contract was up for renewal, Steph and I had already agreed not to continue with IRRI, but take early retirement and return to the UK.

But not quite yet. IRRI’s Director General, Bob Zeigler, persuaded me to stay on for another year, and organize the celebrations for the institute’s 50th anniversary. Which I duly did, and had great fun doing so.

But as our retirement date approached in April 2010, I was honored by the institute’s Board of Trustees with a farewell party (despedida) coinciding with the 50th anniversary of the very first Board meeting in April 1960.

14 April 2010 – IRRI’s 50th celebration dinner and our despedida.

Friday 30 April was my last day in the office.

With my DPPC friends. L-R: Eric, Corinta, Zeny, me, Vhel, and Yeyet.

We flew back to the UK two days later, arriving on Monday 3 May and taking delivery of our new car, a Peugeot 308, the following day.

Philippa and Andi flew off to New York in October 2010 and were married in Central Park. She graduated with her PhD in December.

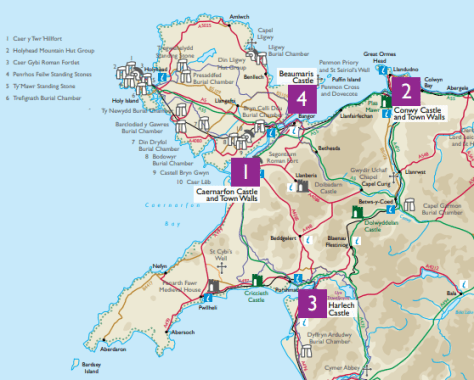

By 2013 we had been married for four decades, and were well-settled into retirement, enjoying all the opportunities good weather gave us to really explore Worcestershire and neighboring counties, especially as National Trust and English Heritage members. And touring Scotland in 2015, Northern Ireland in 2017, Cornwall in 2018, East Sussex and Kent in 2019, and Hampshire and West Sussex in 2022.

We were, by then, the proud grandparents of three beautiful boys and a girl.

Callum Andrew (August 2010) – St Paul, Minnesota

Elvis Dexter (September 2011) – Newcastle upon Tyne

Zoë Isobel (May 2012) – St Paul, Minnesota

Felix Sylvester (September 2013) – Newcastle upon Tyne

And how could we ever forget a very special day in February 2012, when Steph, Philippa and my former colleague from IRRI, Corinta joined me at Buckingham Palace for an investiture.

Receiving my OBE from King Charles III (then HRH The Prince of Wales) on 14 February 2012.

With Steph and Philippa outside the gates of Buckingham Palace.

With Corinta and Steph in the courtyard of Buckingham Palace after the investiture.

Since 2010, we have traveled to the USA each year except during the pandemic years (2020-2022), and only returning there this past May and June. We’ve made some pretty impressive road trips around the USA, taking in the east and west coasts, and all points in between with the exception of the Deep South. Just click here to find a list of those road trips.

In July 2016, a few months after I broke my leg, Hannah and family came over to the UK, and we got together with Phil and Andi and the boys for the first time, sharing a house in the New Forest.

Our first group photo as a family, near Beaulieu Road station in the New Forest, 7 July 2016. L-R: Zoë, Michael, me (still using a walking stick), Steph, Callum, Hannah, Elvis, Andi, Felix, and Philippa.

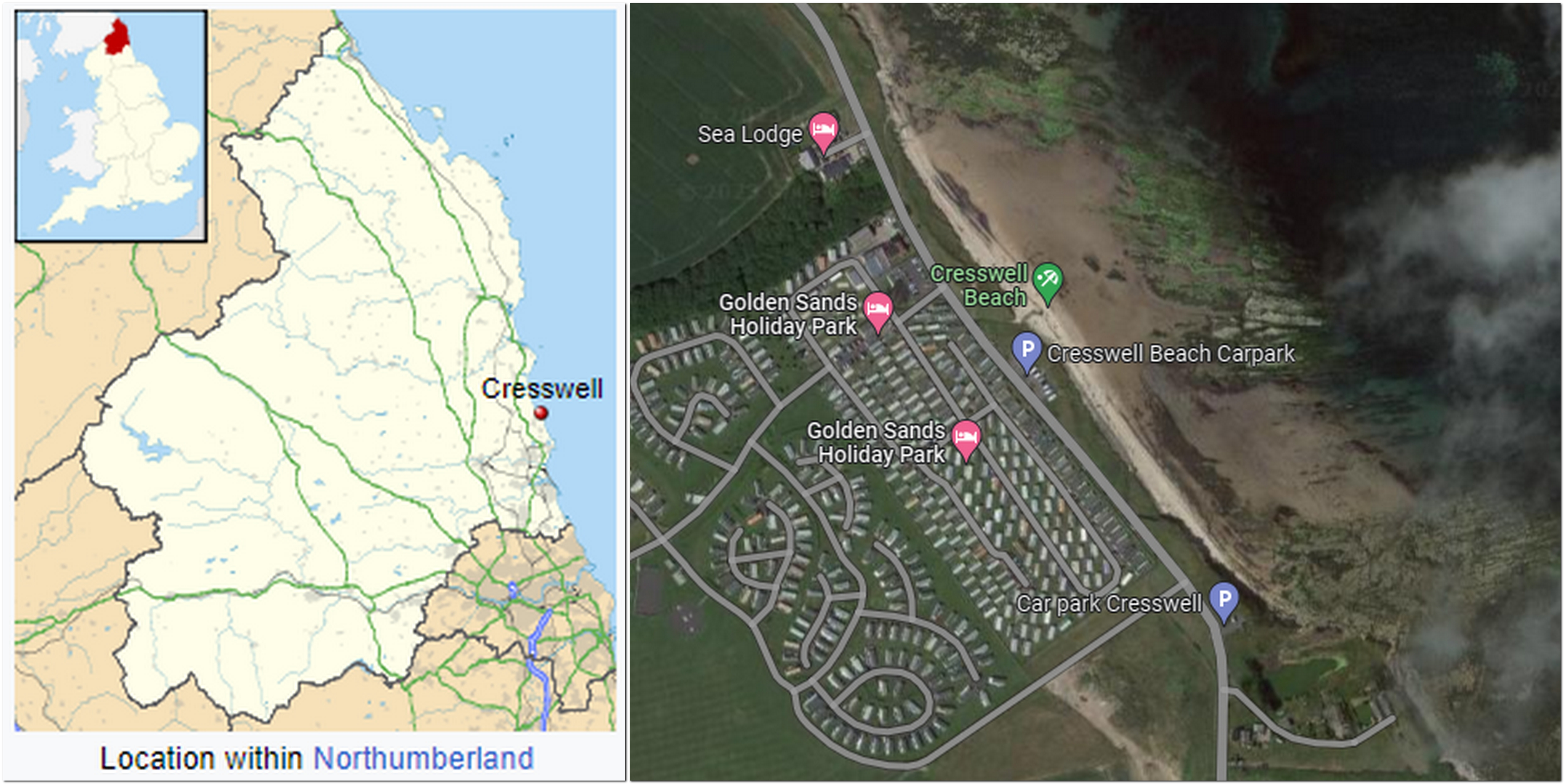

And they came over again in July 2022, to our new home in the northeast of England where we had moved from Bromsgrove in October 2020 at the height of the Covid-19 pandemic.

In our garden in Backworth, North Tyneside, August 2022.

L-R: Felix, Elvis, Zoë, and Callum, at Dunstanburgh Castle, Northumberland in August 2022.

So it’s 2023, and fifty years have passed since we married.

During our visit to the USA this past May and June, we met up with Roger Rowe and his wife Norma, along the Mississippi River at La Crosse in Wisconsin.

Roger joined CIP in 1973 as head of the Breeding and Genetics Department and was our first boss. Roger also co-supervised my PhD. So it was great meeting up with them again 50 years on.

We’ve been in the northeast just over three years now, and haven’t regretted for a moment making the move north. It’s a wonderful part of the country, and in fact has given us a new lease of life.

At Steel Rigg looking east towards the Whin Sill, Crag Lough, and Hadrian’s Wall, Northumberland, February 2022.

Steph has taken great pleasure in developing her new garden here. It’s a work in progress, and quite a different challenge from her garden in Worcestershire, discovering what she can grow and what won’t survive this far north or in the very heavy (and often waterlogged) soil.

22 August 2023

I’ve had much enjoyment writing this blog since 2012, combining my interests of writing and photography. It has certainly given me a focus in retirement. I never thought I’d still be writing as many stories, over 700 now, and approaching 780,000 words. Since returning to the UK, I’ve also tried to take a daily walk of 2-4 miles. However, that’s not been possible these past six months. A back and leg problem has curtailed my daily walk, but I’m hopeful that it will eventually resolve itself and I’ll be able to get out and about locally, especially along the famous North Tyneside waggonways.

After 50 years together, we have much to be thankful for. We’ve enjoyed the countries where we have lived and worked, or visited on vacation. Our daughters and their families are thriving. Hannah is a Senior Director of Talent Management and Strategy for one of the USA’s largest food companies, and Philippa is an Associate Professor of Biological Psychology at Northumbria University.

Sisters!

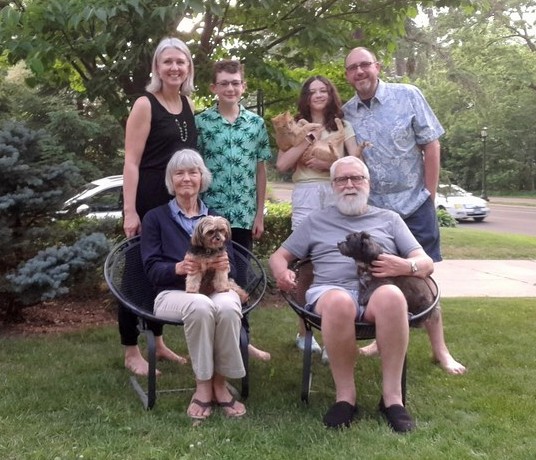

With Hannah and Michael, Callum and Zoë (and doggies Bo and Ollie, and cat Hobbes) in St Paul, MN on 18 June 2023.

With Philippa and Andi, Elvis and Felix (and doggies Rex and Noodle) on 2 September 2023.

And here we are, at South Stack cliffs, in the prime of life (taken in mid-September) when we enjoyed a short break in North Wales.

Steph with Philippa and family on her birthday on 8 October.

13 October 2023 – still going strong!

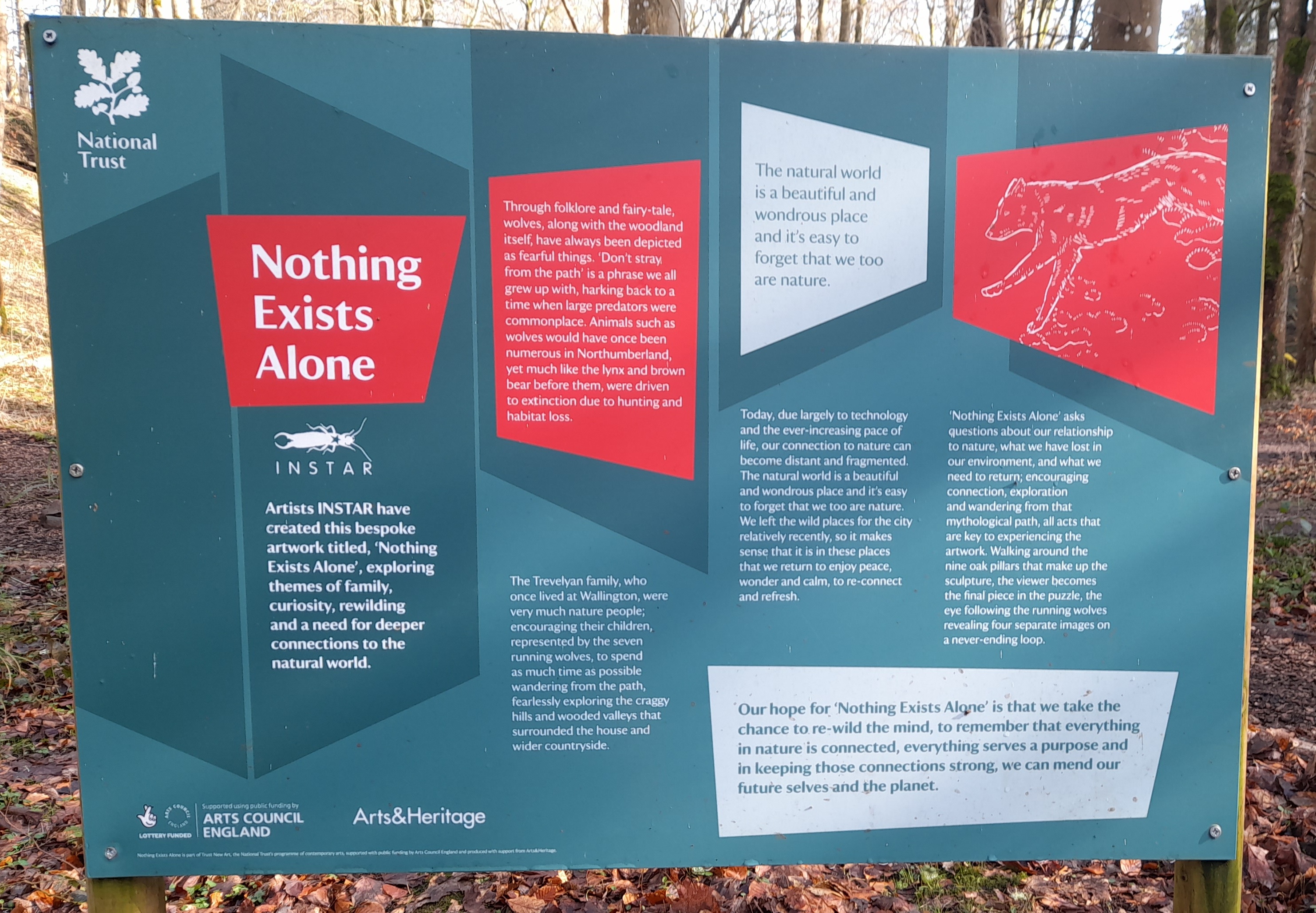

While drafting this reminiscence, I came across this article by Hannah Snyder on the Northwest Public Broadcasting website, and it inspired the title I used.

Along the path beside the Garden Pond, there’s a newly installed sculpture of an owl, carved from one of the downed trees, standing in open woodland (mainly of beech) but with lots of understorey bushes.

Along the path beside the Garden Pond, there’s a newly installed sculpture of an owl, carved from one of the downed trees, standing in open woodland (mainly of beech) but with lots of understorey bushes.

We walked through the walled garden, and enjoyed the crocus lawns at their best on the upper terrace, before heading through the gate that led to the River Walk path.

We walked through the walled garden, and enjoyed the crocus lawns at their best on the upper terrace, before heading through the gate that led to the River Walk path.

A wealthy cloth merchant,

A wealthy cloth merchant,

John, a plant pathologist working on bacterial diseases of potato, was a colleague of ours at the

John, a plant pathologist working on bacterial diseases of potato, was a colleague of ours at the

It’s by chance, I suppose, that Steph and I got together in the first place. We met at the University of Birmingham, where we studied for our MSc degrees in

It’s by chance, I suppose, that Steph and I got together in the first place. We met at the University of Birmingham, where we studied for our MSc degrees in  But fate stepped in I guess.

But fate stepped in I guess.

While we were allowed to post marriage banns in the British Embassy, we had to announce our intention to marry in the official Peruvian government gazette, El Peruano, and one of the principal daily broadsheets (El Comercio if memory serves me right), and have the police visit us at our apartment to verify our address. I think we also had to have blood tests as well. This all took time, but everything was eventually in place for us to set the wedding date: 13 October.

While we were allowed to post marriage banns in the British Embassy, we had to announce our intention to marry in the official Peruvian government gazette, El Peruano, and one of the principal daily broadsheets (El Comercio if memory serves me right), and have the police visit us at our apartment to verify our address. I think we also had to have blood tests as well. This all took time, but everything was eventually in place for us to set the wedding date: 13 October.

Steph became an enthusiastic beader and has made several hundred pieces of jewelry since then. In Los Baños we had a live-in helper, Lilia, and so in the heat of Los Baños, Steph was spared the drudgery of housework or cooking, and could focus on the hobbies she enjoyed, including a daily swim in the IRRI pool, and looking after her garden and orchids.

Steph became an enthusiastic beader and has made several hundred pieces of jewelry since then. In Los Baños we had a live-in helper, Lilia, and so in the heat of Los Baños, Steph was spared the drudgery of housework or cooking, and could focus on the hobbies she enjoyed, including a daily swim in the IRRI pool, and looking after her garden and orchids.

Speke Hall

Speke Hall

There were a number of tenants over the centuries, the most prominent being

There were a number of tenants over the centuries, the most prominent being

Bodnant

Bodnant

Like other gardens we have visited (such as Cragside in Northumberland), it never ceases to amaze me what vision the creators of these gardens had. They introduced and planted all manner of species, with many trees today reaching skywards more than 100 feet (among them various redwoods), a landscape they could only have dreamed about but never seen. It has been left to their descendants to nurture that vision alongside the National Trust.

Like other gardens we have visited (such as Cragside in Northumberland), it never ceases to amaze me what vision the creators of these gardens had. They introduced and planted all manner of species, with many trees today reaching skywards more than 100 feet (among them various redwoods), a landscape they could only have dreamed about but never seen. It has been left to their descendants to nurture that vision alongside the National Trust.

According to the legend, Llywelyn returned from a hunting trip (when—unusually—he hadn’t taken Gelert along), only to find his son missing from his cradle, and the dog covered in blood. Believing that the dog had killed his son, he thrust his sword through its heart. At that moment he heard a cry and discovered his son was alive. Beside the boy was a dead wolf that Gelert had killed while saving the baby. Grief-stricken, Llywelyn buried the hound where we now find the grave.

According to the legend, Llywelyn returned from a hunting trip (when—unusually—he hadn’t taken Gelert along), only to find his son missing from his cradle, and the dog covered in blood. Believing that the dog had killed his son, he thrust his sword through its heart. At that moment he heard a cry and discovered his son was alive. Beside the boy was a dead wolf that Gelert had killed while saving the baby. Grief-stricken, Llywelyn buried the hound where we now find the grave.

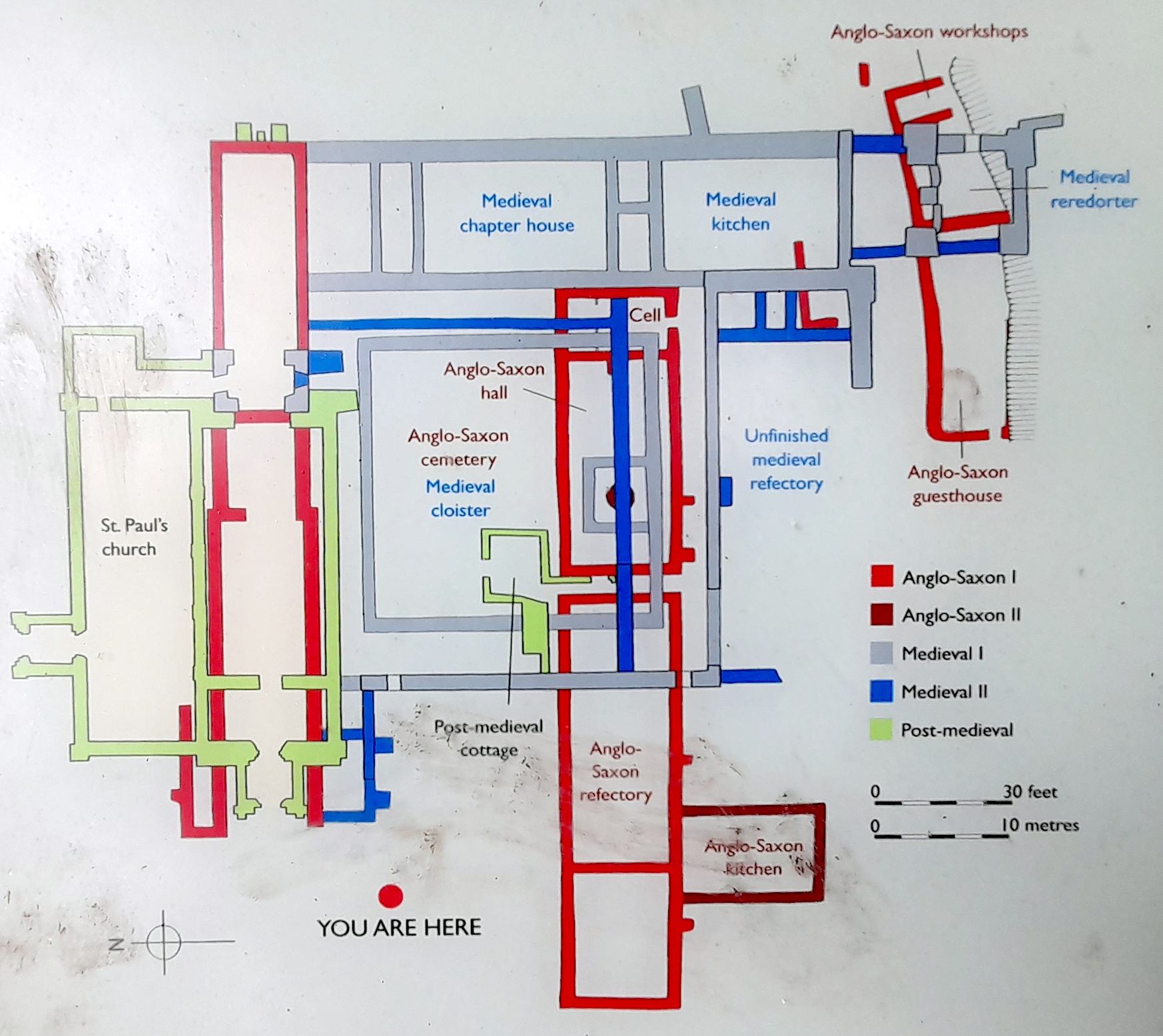

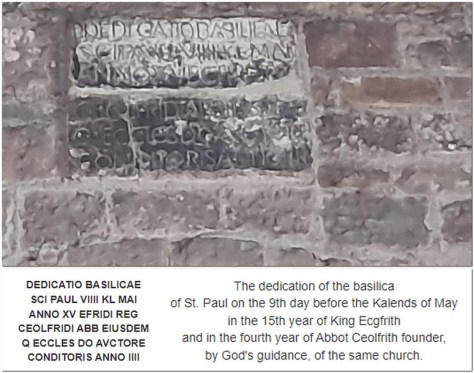

towards South Shields, Jarrow, and Hebburn on the A185, and a brown sign for Jarrow Hall and St Paul’s, with the English Heritage logo (right) prominently displayed. A road we’d not been down until last week.

towards South Shields, Jarrow, and Hebburn on the A185, and a brown sign for Jarrow Hall and St Paul’s, with the English Heritage logo (right) prominently displayed. A road we’d not been down until last week.

The church and monastery were built on land given by

The church and monastery were built on land given by

Anyway, the forecast for yesterday seemed hopeful, so we decided to make the short, 22 mile and 30 minute drive south to Durham to take in Crook Hall Gardens. The Trust acquired the property in 2022, and if I understood correctly, it was opened to the public for the first time in March this year.

Anyway, the forecast for yesterday seemed hopeful, so we decided to make the short, 22 mile and 30 minute drive south to Durham to take in Crook Hall Gardens. The Trust acquired the property in 2022, and if I understood correctly, it was opened to the public for the first time in March this year. Crook Hall was a family home since the 1300s, and occupied over the centuries by several families who stamped their mark on the property. Originally it was the home of the Billingham family for 300 years from 1372. Between 1834 and 1858 it was rented by the Raine family. Canon

Crook Hall was a family home since the 1300s, and occupied over the centuries by several families who stamped their mark on the property. Originally it was the home of the Billingham family for 300 years from 1372. Between 1834 and 1858 it was rented by the Raine family. Canon

The local supermarket, Lunds & Byerlys has relocated a couple of blocks west along Ford Parkway to Highland Bridge. On the first floor they have opened The Mezz Taproom—with a terrace overlooking the new development—where you have the choice of about 20+ beers on tap, plus some wines. Michael took me there one blisteringly hot afternoon a few days after we arrived in St Paul.

The local supermarket, Lunds & Byerlys has relocated a couple of blocks west along Ford Parkway to Highland Bridge. On the first floor they have opened The Mezz Taproom—with a terrace overlooking the new development—where you have the choice of about 20+ beers on tap, plus some wines. Michael took me there one blisteringly hot afternoon a few days after we arrived in St Paul.

So it was with some slight trepidation that I went online at the end of January and booked flights to the Twin Cities with Delta, to depart from Newcastle International Airport (NCL) on 29 May, and returning from Minneapolis-St Paul (MSP) on 19 June. And with both schedules transiting through Schipol (AMS). Until Delta made a schedule change for us, and had us returning via Detroit (DTW) and AMS.

So it was with some slight trepidation that I went online at the end of January and booked flights to the Twin Cities with Delta, to depart from Newcastle International Airport (NCL) on 29 May, and returning from Minneapolis-St Paul (MSP) on 19 June. And with both schedules transiting through Schipol (AMS). Until Delta made a schedule change for us, and had us returning via Detroit (DTW) and AMS.

Once again, Steph and I were directed to the front of the queue and once on board, settled ourselves into seats 30A and B in the Delta Comfort+ section of the economy cabin.

Once again, Steph and I were directed to the front of the queue and once on board, settled ourselves into seats 30A and B in the Delta Comfort+ section of the economy cabin.

By 1976, Steph and I had moved to Costa Rica, where I was CIP’s regional leader for Mexico, Central America, and the Caribbean. In early 1980, I was returning from a trip to the Dominican Republic, and transiting overnight in Miami. Joining one of the (interminable) immigration queues, I looked over to my right and, lo and behold to my surprise, Dave was just a couple of passengers ahead of me in the parallel queue. He had just flown in from the UK, on his way to Bolivia, his second expedition there. He had a connecting flight, and once we were both through immigration we only had about 15 minutes to chat before he had to find his boarding gate. What a coincidence!

By 1976, Steph and I had moved to Costa Rica, where I was CIP’s regional leader for Mexico, Central America, and the Caribbean. In early 1980, I was returning from a trip to the Dominican Republic, and transiting overnight in Miami. Joining one of the (interminable) immigration queues, I looked over to my right and, lo and behold to my surprise, Dave was just a couple of passengers ahead of me in the parallel queue. He had just flown in from the UK, on his way to Bolivia, his second expedition there. He had a connecting flight, and once we were both through immigration we only had about 15 minutes to chat before he had to find his boarding gate. What a coincidence!

However, by 1990, Trevor had left IBPGR and was working out of Washington, DC, helping to set up the International Network for Bamboo and Rattan (INBAR, now the

However, by 1990, Trevor had left IBPGR and was working out of Washington, DC, helping to set up the International Network for Bamboo and Rattan (INBAR, now the

During the

During the

Steph and I joined the

Steph and I joined the

Built in 1872, there have been numerous famous visitors, among them comedy duo

Built in 1872, there have been numerous famous visitors, among them comedy duo