I published my first scientific paper in 1972. It described a new technique to make root tip squashes to count chromosomes, and it was published in the August 1972 volume of the Journal of Microscopy. It came out of the work I did for my MSc dissertation on lentils and their origin.

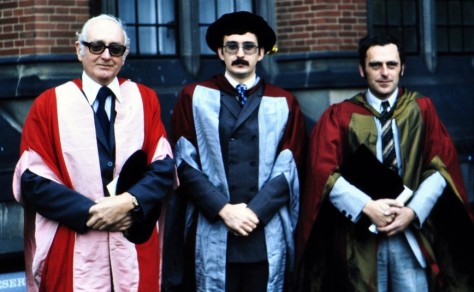

Then in January 1973 I entered the world of work, and for the next 37 years until my retirement in April 2010, I worked as a research scientist or research manager at just three organizations (although I actually held five different positions) at: the International Potato Center (CIP) in Peru (1973-1981); The University of Birmingham (1981-1991); and the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) in the Philippines (1991-2010).

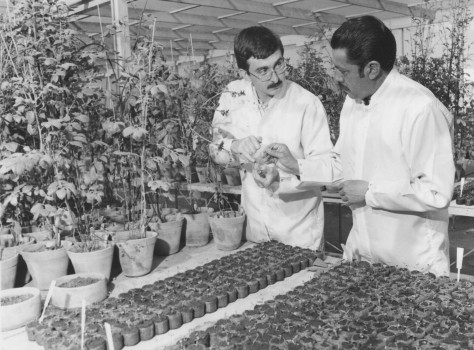

The focus of my research was primarily the conservation and use of plant genetic resources, specifically of potatoes, grain legumes, and rice, with biosystematics and genetic diversity, as well as different approaches to germplasm conservation, being particular themes. But I also studied potato diseases and agronomy.

So as much for my own interest and anyone else who might like to review my scientific contributions, this blog post relates specifically to my refereed papers, books, chapters, and other miscellaneous publications that I have written over the decades.

Science is a collaborative endeavour, and I have been extremely fortunate to have had the opportunity of working with some outstanding colleagues from different organizations around the world, as well as supervising the research of great graduate students at Birmingham for their PhD degrees, or staff at the Genetic Resources Center at IRRI. But having taken on a senior management role at IRRI in 2001 there was obviously less opportunity thereafter to engage in scientific publication, apart from several legacy studies from my active research years.

I have provided links to PDF copies of these papers where available. And I have also given, in [ ], the number of citations for each (details from Google Scholar, where available, as of 24 March 2024).

PAPERS IN REFEREED JOURNALS

Biosystematics & germplasm diversity

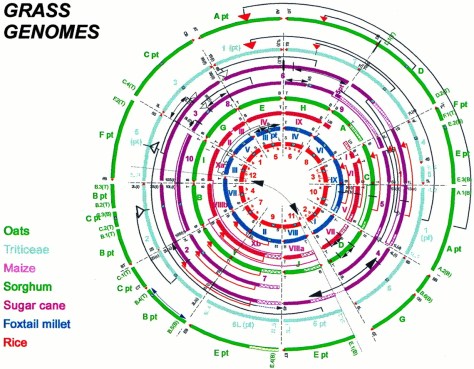

I trained as a biosystematist looking at the species relationships of lentils and potatoes. So when I moved to IRRI in 1991, I decided that we needed to understand better the germplasm collection (now more than 117,000 seed accessions of cultivated and wild rices) in terms of species range and relationships. Over the next 10 years we invested in a significant effort to study the AA genome species most closely related to cultivated rice, Oryza sativa. We also reported some of the first applications of molecular markers to study a germplasm collection, and one of the first—if not the first—studies in association genetics, in a collaboration with The University of Birmingham and the John Innes Centre, Norwich.

The 39 papers listed here cover work on potatoes, rice, lentil, grass pea (Lathyrus), and a fodder legume, tagasaste, from the Canary Islands.

Damania, A.B., M.T. Jackson & E. Porceddu, 1984. Variation in wheat and barley landraces from Nepal and the Yemen Arab Republic. Zeitschrift für Pflanzenzüchtung 94, 13-24. PDF [21]

Ford-Lloyd, B.V., D. Brar, G.S. Khush, M.T. Jackson & P.S. Virk, 2008. Genetic erosion over time of rice landrace agrobiodiversity. Plant Genetic Resources: Characterization and Utilization 7(2), 163-168. PDF [27]

Ford-Lloyd, B.V., M.T. Jackson & A. Santos Guerra, 1982. Beet germplasm in the Canary Islands. Plant Genetic Resources Newsletter 50, 24-27. PDF [2]

Ford-Lloyd, B.V., H.J. Newbury, M.T. Jackson & P.S. Virk, 2001. Genetic basis for co-adaptive gene complexes in rice (Oryza sativa L.) landraces. Heredity 87, 530-536. PDF [24]

Francisco-Ortega, J. & M.T. Jackson, 1992. The use of discriminant function analysis to study diploid and tetraploid cytotypes of Lathyrus pratensis L. (Fabaceae: Faboideae). Acta Botanica Neerlandica 41, 63-73. PDF [4]

Francisco-Ortega, J., M.T. Jackson, J.P. Catty & B.V. Ford-Lloyd, 1992. Genetic diversity in the Chamaecytisus proliferus (L. fil.) Link complex (Fabaceae: Genisteae) in the Canary Islands in relation to in situ conservation. Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution 39, 149-158. PDF [23]

Francisco-Ortega, F.J., M.T. Jackson, A. Santos-Guerra & M. Fernandez-Galvan, 1990. Genetic resources of the fodder legumes tagasaste and escobón (Chamaecytisus proliferus (L. fil.) Link sensu lato) in the Canary Islands. Plant Genetic Resources Newsletter 81/82, 27-32. PDF [15]

Francisco-Ortega, J., M.T. Jackson, A. Santos-Guerra & M. Fernandez-Galvan, 1991. Historical aspects of the origin and distribution of tagasaste (Chamaecytisus proliferus (L. fil.) Link ssp. palmensis (Christ) Kunkel), a fodder tree from the Canary Islands. Journal of the Adelaide Botanical Garden 14, 67-76. PDF [31]

Francisco-Ortega, J., M.T. Jackson, A. Santos-Guerra & B.V. Ford-Lloyd, 1993. Morphological variation in the Chamaecytisus proliferus (L. fil.) Link complex (Fabaceae: Genisteae) in the Canary Islands. Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society 112, 187-202. PDF [9]

Francisco-Ortega, J., M.T. Jackson, A. Santos-Guerra, M. Fernandez-Galvan & B.V. Ford-Lloyd, 1994. The phytogeography of the Chamaecytisus proliferus (L. fil.) Link (Fabaceae: Genisteae) complex in the Canary Islands: a multivariate analysis. Vegetatio 110, 1-17. PDF [11]

Francisco-Ortega, J., M.T. Jackson, A.R. Socorro-Monzon & B.V. Ford-Lloyd, 1992. Ecogeographical characterization of germplasm of tagasaste and escobón (Chamaecytisus proliferus (L. Fil.) Link sensu lato) from the Canary Islands: soil, climatological and geographical features. Investigación Agraria: Producción y Protección Vegetal 7, 377-388. PDF

Gubb, I.R., J.C. Hughes, M.T. Jackson & J.A. Callow, 1989. The lack of enzymic browning in the wild potato species Solanum hjertingii Hawkes compared with commercial Solanum tuberosum varieties. Annals of Applied Biology 114, 579-586. PDF [14]

Jackson, M.T. 1975. The evolutionary significance of the triploid cultivated potato, Solanum x chaucha Juz. et Buk. PhD thesis, University of Birmingham. [10]

Jackson, M.T., J.G. Hawkes & P.R. Rowe, 1977. The nature of Solanum x chaucha Juz. et Buk., a triploid cultivated potato of the South American Andes. Euphytica 26, 775-783. PDF [39]

Jackson, M.T., J.G. Hawkes & P.R. Rowe, 1980. An ethnobotanical field study of primitive potato varieties in Peru. Euphytica 29, 107-113. PDF [58]

Jackson, M.T., P.R. Rowe & J.G. Hawkes, 1978. Crossability relationships of Andean potato varieties of three ploidy levels. Euphytica 27, 541-551. PDF [45]

Jackson, M.T. & A.G. Yunus, 1984. Variation in the grasspea, Lathyrus sativus L. and wild species. Euphytica 33, 549-559. PDF [170]

Juliano, A.B., M.E.B. Naredo & M.T. Jackson, 1998. Taxonomic status of Oryza glumaepatula Steud. I. Comparative morphological studies of New World diploids and Asian AA genome species. Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution 45, 197-203. PDF [40]

Juliano, A.B., M.E.B. Naredo, B.R. Lu & M.T. Jackson, 2005. Genetic differentiation in Oryza meridionalis Ng based on molecular and crossability analyses. Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution 52, 435-445. PDF [18]

Juned, S.A., M.T. Jackson & J.P. Catty, 1988. Diversity in the wild potato species Solanum chacoense Bitt. Euphytica 37, 149-156. PDF [32]

Juned, S.A., M.T. Jackson & B.V. Ford-Lloyd, 1991. Genetic variation in potato cv. Record: evidence from in vitro “regeneration ability”. Annals of Botany 67, 199-203. PDF [3]

Lu, B.R., M.E.B. Naredo, A.B. Juliano & M.T. Jackson, 1997. Hybridization of AA genome rice species from Asia and Australia. II. Meiotic analysis of Oryza meridionalis and its hybrids. Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution 44, 25-31. PDF [26]

Lu, B.R., M.E.B. Naredo, A.B. Juliano & M.T. Jackson, 1998. Taxonomic status of Oryza glumaepatula Steud. III. Assessment of genomic affinity among AA genome species from the New World, Asia, and Australia. Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution 45, 215-223. PDF [25]

Martin, C., A. Juliano, H.J. Newbury, B.R. Lu, M.T. Jackson & B.V. Ford-Lloyd, 1997. The use of RAPD markers to facilitate the identification of Oryza species within a germplasm collection. Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution 44, 175-183. PDF [80]

Naredo, M.E.B., A.B. Juliano, B.R. Lu & M.T. Jackson, 1997. Hybridization of AA genome rice species from Asia and Australia. I. Crosses and development of hybrids. Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution 44, 17-23. PDF [52]

Naredo, M.E.B., A.B. Juliano, B.R. Lu & M.T. Jackson, 1998. Taxonomic status of Oryza glumaepatula Steud. II. Hybridization between New World diploids and AA genome species from Asia and Australia. Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution 45, 205-214. PDF [35]

Naredo, M.E.B., A.B. Juliano, B.R. Lu & M.T. Jackson, 2003. The taxonomic status of the wild rice species Oryza ridleyi Hook. f. and O. longiglumis Jansen (Ser. Ridleyanae Sharma et Shastry) from Southeast Asia. Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution. Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution 50, 477-488. PDF [9]

Parsons, B.J., H.J. Newbury, M.T. Jackson & B.V. Ford-Lloyd, 1997. Contrasting genetic diversity relationships are revealed in rice (Oryza sativa L.) using different marker types. Molecular Breeding 3, 115-125. PDF [217]

Parsons, B., H.J. Newbury, M.T. Jackson & B.V. Ford-Lloyd, 1999. The genetic structure and conservation of aus, aman and boro rices from Bangladesh. Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution 46, 587-598. PDF [57]

Virk, P.S., B.V. Ford-Lloyd, M.T. Jackson & H.J. Newbury, 1995. Use of RAPD for the study of diversity within plant germplasm collections. Heredity 74, 170-179. PDF [383]

Virk, P.S., B.V. Ford-Lloyd, M.T. Jackson, H.S. Pooni, T.P. Clemeno & H.J. Newbury, 1996. Predicting quantitative variation within rice using molecular markers. Heredity 76, 296-304. PDF [233]

Virk, P.S., H.J. Newbury, M.T. Jackson & B.V. Ford-Lloyd, 1995. The identification of duplicate accessions within a rice germplasm collection using RAPD analysis. Theoretical and Applied Genetics 90, 1049-1055. PDF [207]

Virk, P.S., H.J. Newbury, M.T. Jackson & B.V. Ford-Lloyd, 2000. Are mapped markers more useful for assessing genetic diversity? Theoretical and Applied Genetics 100, 607-613. PDF [92]

Virk, P.S., J. Zhu, H.J. Newbury, G.J. Bryan, M.T. Jackson & B.V. Ford-Lloyd, 2000. Effectiveness of different classes of molecular marker for classifying and revealing variation in rice (Oryza sativa) germplasm. Euphytica 112, 275-284. PDF [207]

Williams, J.T., A.M.C. Sanchez & M.T. Jackson, 1974. Studies on lentils and their variation. I. The taxonomy of the species. Sabrao Journal 6, 133-145. PDF [61]

Woodwards, L. & M.T. Jackson, 1985. The lack of enzymic browning in wild potato species, Series Longipedicellata, and their crossability with Solanum tuberosum. Zeitschrift für Pflanzenzüchtung 94, 278-287. PDF [24]

Yunus, A.G. & M.T. Jackson, 1991. The gene pools of the grasspea (Lathyrus sativus L.). Plant Breeding 106, 319-328. PDF [65]

Yunus, A.G., M.T. Jackson & J.P. Catty, 1991. Phenotypic polymorphism of six isozymes in the grasspea (Lathyrus sativus L.). Euphytica 55, 33-42. PDF [36]

Zhu, J., M.D. Gale, S. Quarrie, M.T. Jackson & G.J. Bryan, 1998. AFLP markers for the study of rice biodiversity. Theoretical and Applied Genetics 96, 602-611. PDF [271]

Zhu, J.H., P. Stephenson, D.A. Laurie, W. Li, D. Tang, M.T. Jackson & M.D. Gale, 1999. Towards rice genome scanning by map-based AFLP fingerprinting. Molecular and General Genetics 261, 184-295. PDF [30]

Germplasm conservation

The 14 papers in this section focus primarily on studies we carried out at IRRI to enhance the conservation of rice seeds. It’s interesting to note that new research on seed drying just published by seed physiologist Fiona Hay and colleagues at IRRI has thrown some doubt on the seed drying measures we introduced in the mid-1990s. But there is much more to learn, and after all, that’s the way of science.

Appa Rao, S., C. Bounphanouxay, V. Phetpaseut, J.M. Schiller, V. Phannourath & M.T. Jackson, 1997. Collection and preservation of rice germplasm from southern and central regions of the Lao PDR. Lao Journal of Agriculture and Forestry 1, 43-56. PDF [13]

Appa Rao, S., C. Bounphanousay, J.M. Schiller & M.T. Jackson, 2002. Collection, classification, and conservation of cultivated and wild rices of the Lao PDR. Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution 49, 75-81. PDF [48]

Appa Rao, S., C. Bounphanousay, J.M. Schiller, A.P. Alcantara & M.T. Jackson, 2002. Naming of traditional rice varieties by farmers in the Lao PDR. Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution 49, 83-88. PDF [67]

Ellis, R.H., T.D. Hong & M.T. Jackson, 1993. Seed production environment, time of harvest, and the potential longevity of seeds of three cultivars of rice (Oryza sativa L.). Annals of Botany 72, 583-590. PDF [166]

Ellis, R.H. & M.T. Jackson, 1995. Accession regeneration in genebanks: seed production environment and the potential longevity of seed accessions. Plant Genetic Resources Newsletter 102, 26-28. PDF [13]

Ford-Lloyd, B.V. & M.T. Jackson, 1991. Biotechnology and methods of conservation of plant genetic resources. Journal of Biotechnology 17, 247-256. PDF [19]

Francisco-Ortega, F.J. & M.T. Jackson, 1993. Conservation strategies for tagasaste and escobón (Chamaecytisus proliferus (L. fil.) Link) in the Canary Islands. Boletim do Museu Municipal do Funchal, Sup. N° 2, 99-105. PDF

Kameswara Rao, N. & M.T. Jackson, 1996. Seed longevity of rice cultivars and strategies for their conservation in genebanks. Annals of Botany 77, 251-260. PDF [79]

Kameswara Rao, N. & M.T. Jackson, 1996. Seed production environment and storage longevity of japonica rices (Oryza sativa L.). Seed Science Research 6, 17-21. PDF [47]

Kameswara Rao, N. & M.T. Jackson, 1996. Effect of sowing date and harvest time on longevity of rice seeds. Seed Science Research 7, 13-20. PDF [31]

Kameswara Rao, N. & M.T. Jackson, 1997. Variation in seed longevity of rice cultivars belonging to different isozyme groups. Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution 44, 159-164. PDF [40]

Kiambi, D.K., B.V. Ford-Lloyd, M.T. Jackson, L. Guarino, N. Maxted & H.J. Newbury, 2005. Collection of wild rice (Oryza L.) in east and southern Africa in response to genetic erosion. Plant Genetic Resources Newsletter 142, 10-20. PDF [23]

Loresto, G.C., E. Guevarra & M.T. Jackson, 2000. Use of conserved rice germplasm. Plant Genetic Resources Newsletter 124, 51-56. PDF [11]

Naredo, M.E.B., A.B. Juliano, B.R. Lu, F. de Guzman & M.T. Jackson, 1998. Responses to seed dormancy-breaking treatments in rice species (Oryza L.). Seed Science and Technology 26, 675-689. PDF [98]

Germplasm evaluation & use

These five papers come from the work of some of my graduate students, looking primarily at the resistance of wild potato species to a range of pests and diseases, especially potato cyst nematode.

Andrade-Aguilar, J.A. & M.T. Jackson, 1988. Attempts at interspecific hybridization between Phaseolus vulgaris L. and P. acutifolius A. Gray using embryo rescue. Plant Breeding 101, 173-180. PDF [33]

Chávez, R., M.T. Jackson, P.E. Schmiediche & J. Franco, 1988. The importance of wild potato species resistant to the potato cyst nematode, Globodera pallida, pathotypes P4A and P5A, in potato breeding. I. Resistance studies. Euphytica 37, 9-14. PDF [25]

Chávez, R., M.T. Jackson, P.E. Schmiediche & J. Franco, 1988. The importance of wild potato species resistant to the potato cyst nematode, Globodera pallida, pathotypes P4A and P5A, in potato breeding. II. The crossability of resistant species. Euphytica 37, 15-22. PDF [14]

Chávez, R., P.E. Schmiediche, M.T. Jackson & K.V. Raman, 1988. The breeding potential of wild potato species resistant to the potato tuber moth, Phthorimaea operculella (Zeller). Euphytica 39, 123-132. PDF [50]

Jackson, M.T., J.G. Hawkes, B.S. Male-Kayiwa & N.W.M. Wanyera, 1988. The importance of the Bolivian wild potato species in breeding for Globodera pallida resistance. Plant Breeding 101, 261-268. PDF [17]

Plant pathology & agronomy

Just three papers in this section. In the mid-1970s when I was based in Turrialba, I did some important work on bacterial wilt of potatoes.

Jackson, M.T., L.F. Cartín & J.A. Aguilar, 1981. El uso y manejo de fertilizantes en el cultivo de la papa (Solanum tuberosum L.) en Costa Rica. Agronomía Costarricense 5, 15-19. PDF [8]

Jackson, M.T. & L.C. González, 1981. Persistence of Pseudomonas solanacearum (Race 1) in a naturally infested soil in Costa Rica. Phytopathology 71, 690-693. PDF [38]

Jackson, M.T., L.C. González & J.A. Aguilar, 1979. Avances en el combate de la marchitez bacteriana de papa en Costa Rica. Fitopatología 14, 46-53. PDF [8]

Reviews

Hawkes, J.G. & M.T. Jackson, 1992. Taxonomic and evolutionary implications of the Endosperm Balance Number hypothesis in potatoes. Theoretical and Applied Genetics 84, 180-185. PDF [83]

Jackson, M.T., 1986. The potato. The Biologist 33, 161-167. PDF

Jackson, M.T., 1990. Vavilov’s Law of Homologous Series – is it relevant to potatoes? Biological Journal of the Linnean Society 39, 17-25. PDF [4]

Jackson, M.T., 1991. Biotechnology and the environment: a Birmingham perspective. Journal of Biotechnology 17, 195-198. PDF

Jackson, M.T., 1995. Protecting the heritage of rice biodiversity. GeoJournal 35, 267-274. PDF [92]

Jackson, M.T., 1997. Conservation of rice genetic resources: the role of the International Rice Genebank at IRRI. Plant Molecular Biology 35, 61-67. PDF [134]

Techniques

Andrade-Aguilar, J.A. & M.T. Jackson, 1988. The insertion method: a new and efficient technique for intra- and interspecific hybridization in Phaseolus beans. Annual Report of the Bean Improvement Cooperative 31, 218-219. [1]

Damania, A.B., E. Porceddu & M.T. Jackson, 1983. A rapid method for the evaluation of variation in germplasm collections of cereals using polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Euphytica 32, 877-883. PDF [51]

Kordan, H.A. & M.T. Jackson, 1972. A simple and rapid permanent squash technique for bulk-stained material. Journal of Microscopy 96, 121-123. PDF [1]

BOOKS

Brian Ford-Lloyd and I wrote one of the first general texts about plant genetic resources and their conservation in 1986. We were also at the forefront in the climate change debate in 1990, and published an update in 2014.

Ford-Lloyd, B.V. & M.T. Jackson, 1986. Plant Genetic Resources – An Introduction to Their Conservation and Use. Edward Arnold, London, p. 146. [212]

Jackson, M., B.V. Ford-Lloyd & M.L. Parry (eds.), 1990. Climatic Change and Plant Genetic Resources. Belhaven Press, London, p. 190. [20]

Engels, J.M.M., V.R. Rao, A.H.D. Brown & M.T. Jackson (eds.), 2002. Managing Plant Genetic Diversity. CAB International, Wallingford, p. 487.

Jackson, M., B. Ford-Lloyd & M. Parry (eds.), 2014. Plant Genetic Resources and Climate Change. CAB International, Wallingford, p. 291. [36]

BOOK CHAPTERS

There are 21 chapters in this section, and they cover a whole range of topics on germplasm conservation and use, among others.

Appa Rao, S., C. Bounphanousay, J.M. Schiller, M.T. Jackson, P. Inthapanya & K. Douangsila. 2006. The aromatic rice of Laos. In: J.M. Schiller, M.B. Chanphengxay, B. Linquist & S. Appa Rao (eds.), Rice in Laos. Los Baños (Philippines): International Rice Research Institute, pp. 159-174. PDF [1]

Appa Rao, S., J.M. Schiller, C. Bounphanousay, A.P. Alcantara & M.T. Jackson. 2006. Naming of traditional rice varieties by the farmers of Laos. In: J.M. Schiller, M.B. Chanphengxay, B. Linquist & S. Appa Rao (eds.), Rice in Laos. Los Baños (Philippines): International Rice Research Institute, pp. 141-158. PDF [6]

Appa Rao, S., J.M. Schiller, C. Bounphanousay, P. Inthapanya & M.T. Jackson. 2006. The colored pericarp (black) rice of Laos. In: J.M. Schiller, M.B. Chanphengxay, B. Linquist & S. Appa Rao (eds.), Rice in Laos. Los Baños (Philippines): International Rice Research Institute, pp. 175-186. PDF [17]

Appa Rao, S., J.M. Schiller, C. Bounphanousay & M.T. Jackson. 2006. Diversity within the traditional rice varieties of Laos. In: J.M. Schiller, M.B. Chanphengxay, B. Linquist & S. Appa Rao (eds.), Rice in Laos. Los Baños (Philippines): International Rice Research Institute, pp. 123-140. PDF [23]

Appa Rao, S., J.M. Schiller, C. Bounphanousay & M.T. Jackson, 2006. Development of traditional rice varieties and on-farm management of varietal diversity in Laos. In: J.M. Schiller, M.B. Chanphengxay, B. Linquist & S. Appa Rao (eds.), Rice in Laos. Los Baños (Philippines): International Rice Research Institute, pp. 187-196. PDF [3]

Bellon, M.R., J.L. Pham & M.T. Jackson, 1997. Genetic conservation: a role for rice farmers. In: N. Maxted, B.V. Ford-Lloyd & J.G. Hawkes (eds.), Plant Genetic Conservation: the In Situ Approach. Chapman & Hall, London, pp. 263-289. PDF [210]

Ford-Lloyd, B., J.M.M. Engels & M. Jackson, 2014. Genetic resources and conservation challenges under the threat of climate change. In: M. Jackson, B. Ford-Lloyd & M. Parry (eds.), Plant Genetic Resources and Climate Change. CAB International, Wallingford, pp. 16-37. [16]

Ford-Lloyd, B.V., M.T. Jackson & H.J. Newbury, 1997. Molecular markers and the management of genetic resources in seed genebanks: a case study of rice. In: J.A. Callow, B.V. Ford-Lloyd & H.J. Newbury (eds.), Biotechnology and Plant Genetic Resources: Conservation and Use. CAB International, Wallingford, pp. 103-118. PDF [50]

Ford-Lloyd, B.V., M.T. Jackson & M.L. Parry, 1990. Can genetic resources cope with global warming? In: M. Jackson, B.V. Ford-Lloyd & M.L. Parry (eds.), Climatic Change and Plant Genetic Resources. Belhaven Press, London, pp. 179-182. PDF [1]

Jackson, M.T., 1983. Potatoes. In: D.H. Janzen (ed.), Costa Rican Natural History. University of Chicago Press, pp. 103-105. PDF

Jackson, M.T., 1985. Plant genetic resources at Birmingham—sixteen years of training. In: K.L. Mehra & S. Sastrapradja (eds.), Proceedings of the International Symposium on South East Asian Plant Genetic Resources, Jakarta, Indonesia, August 20-24, 1985, pp. 35-38.

Jackson, M.T., 1987. Breeding strategies for true potato seed. In: G.J. Jellis & D.E. Richardson (eds.), The Production of New Potato Varieties: Technological Advances. Cambridge University Press, pp. 248-261. PDF [8]

Jackson, M.T., 1992. UK consumption of the potato and its agricultural production. In: Bioresources – Some UK Perspectives. Institute of Biology, London, pp. 34-37.

Jackson, M.T., 1994. Ex situ conservation of plant genetic resources, with special reference to rice. In: G. Prain & C. Bagalanon (eds.), Local Knowledge, Global Science and Plant Genetic Resources: towards a partnership. Proceedings of the International Workshop on Genetic Resources, UPWARD, Los Baños, Philippines, pp. 11-22.

Jackson, M.T., 1999. Managing genetic resources and biotechnology at IRRI’s rice genebank. In: J.I. Cohen (ed.), Managing Agricultural Biotechnology – Addressing Research Program and Policy Implications. International Service for National Agricultural Research (ISNAR), The Hague, Netherlands and CAB International, UK, pp. 102-109. PDF [4]

Jackson, M.T. & B.V. Ford-Lloyd, 1990. Plant genetic resources – a perspective. In: M. Jackson, B.V. Ford-Lloyd & M.L. Parry (eds.), Climatic Change and Plant Genetic Resources. Belhaven Press, London, pp. 1-17. PDF [23]

Jackson, M.T., G.C. Loresto, S. Appa Rao, M. Jones, E. Guimaraes & N.Q. Ng, 1997. Rice. In: D. Fuccillo, L. Sears & P. Stapleton (eds.), Biodiversity in Trust: Conservation and Use of Plant Genetic Resources in CGIAR Centres. Cambridge University Press, pp. 273-291. PDF [18]

Koo, B., P.G. Pardey & M.T. Jackson, 2004. IRRI Genebank. In: B. Koo, P.G. Pardey, B.D. Wright and others, Saving Seeds – The Economics of Conserving Crop Genetic Resources Ex Situ in the Future Harvest Centres of the CGIAR. CABI Publishing, Wallingford, pp. 89-103. PDF [1]

Lu, B.R., M.E.B. Naredo, A.B. Juliano & M.T. Jackson, 2000. Preliminary studies on the taxonomy and biosystematics of the AA genome Oryza species (Poaceae). In: S.W.L. Jacobs & J. Everett (eds.), Grasses: Systematics and Evolution. CSIRO: Melbourne, pp. 51-58. PDF [41]

Pham, J.L., S.R. Morin, L.S. Sebastian, G.A. Abrigo, M.A. Calibo, S.M. Quilloy, L. Hipolito & M.T. Jackson, 2002. Rice, farmers and genebanks: a case study in the Cagayan Valley, Philippines. In: J.M.M. Engels, V.R. Rao, A.H.D. Brown & M.T. Jackson (eds.), Managing Plant Genetic Diversity. CAB International, Wallingford, pp. 149-160. PDF [10]

Vaughan, D.A. & M.T. Jackson, 1995. The core as a guide to the whole collection. In: T. Hodgkin, A.H.D. Brown, Th.J.L. van Hintum & E.A.V. Morales (eds.), Core Collections of Plant Genetic Resources. John Wiley & Sons, Chichester, pp. 229-239. PDF [17]

MISCELLANEOUS PUBLICATIONS

There are 34 publications here, so-called ‘grey literature’ that were not reviewed before publication.

Aggarwal, R.K., D.S. Brar, G.S. Khush & M.T. Jackson, 1996. Oryza schlechteri Pilger has a distinct genome based on molecular analysis. Rice Genetics Newsletter 13, 58-59. [7]

Appa Rao, S., C. Bounphanousay, K. Kanyavong, V. Phetpaseuth, B. Sengthong, J.M. Schiller, S. Thirasack & M.T. Jackson, 1997. Collection and classification of rice germplasm from the Lao PDR. Part 2. Northern, Southern and Central Regions. Internal report of the National Agricultural Research Center, Department of Agriculture and Extension, Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry, Vientiane, Lao PDR, and Genetic Resources Center, International Rice Research Institute (IRRI), Los Baños, Philippines.

Appa Rao, S., C. Bounphanousay, K. Kanyavong, B. Sengthong, J.M. Schiller & M.T. Jackson, 1999. Collection and classification of Lao rice germplasm, Part 4. Collection Period: September to December 1998. Internal report of the National Agricultural Research Center, National Agriculture and Forestry Research Institute, Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry, Vientiane, Lao PDR, and Genetic Resources Center, International Rice Research Institute (IRRI), Los Baños, Philippines.

Appa Rao, S., C. Bounphanousay, V. Phetpaseuth, K. Kanyavong, B. Sengthong, J.M. Schiller & M.T. Jackson, 1998. Collection and Classification of Lao Rice Germplasm Part 3. Collecting Period – October 1997 to February 1998. Internal report of the National Agricultural Research Center, National Agriculture and Forestry Research Institute, Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry, Vientiane, Lao PDR, and Genetic Resources Center, International Rice Research Institute (IRRI), Los Baños, Philippines.

Appa Rao, S., C. Bounphanousay, V. Phetpaseuth, K. Kanyavong, B. Sengthong, J. M. Schiller, V. Phannourath & M.T. Jackson, 1996. Collection and classification of rice germplasm from the Lao PDR. Part 1. Southern and Central Regions – 1995. Internal report of the National Agricultural Research Center, Dept. of Agriculture and Extension, Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry, Vientiane, Lao PDR, and Genetic Resources Center, International Rice Research Institute (IRRI), Los Baños, Philippines.

Appa Rao, S,. V. Phetpaseut, C. Bounphanousay & M.T. Jackson, 1997. Spontaneous interspecific hybrids in Oryza in Lao PDR. International Rice Research Notes 22, 4-5. [1]

Arnold, M.H., D. Astley, E.A. Bell, J.K.A. Bleasdale, A.H. Bunting, J. Burley, J.A. Callow, J.P. Cooper, P.R. Day, R.H. Ellis, B.V. Ford-Lloyd, R.J. Giles, J.G. Hawkes, J.D. Hayes, G.G. Henshaw, J. Heslop-Harrison, V.H. Heywood, N.L. Innes, M.T. Jackson, G. Jenkins, M.J. Lawrence, R.N. Lester, P. Matthews, P.M. Mumford, E.H. Roberts, N.W. Simmonds, J. Smartt, R.D. Smith, B. Tyler, R. Watkins, T.C. Whitmore & L.A. Withers, 1986. Plant gene conservation. Nature 319, 615. [10]

Cohen, M.B., M.T. Jackson, B.R. Lu, S.R. Morin, A.M. Mortimer, J.L. Pham & L.J. Wade, 1999. Predicting the environmental impact of transgene outcrossing to wild and weedy rices in Asia. In: 1999 PCPC Symposium Proceedings No. 72: Gene flow and agriculture: relevance for transgenic crops. Proceedings of a Symposium held at the University of Keele, Staffordshire, U.K., April 12-14, 1999. pp. 151-157. [15]

Damania, A.B. & M.T. Jackson, 1986. An application of factor analysis to morphological data of wheat and barley landraces from the Bheri river valley, Nepal. Rachis 5, 25-30. [24]

Dao The Tuan, Nguyen Dang Khoi, Luu Ngoc Trinh, Nguyen Phung Ha, Nguyen Vu Trong, D.A. Vaughan & M.T. Jackson, 1995. INSA-IRRI collaboration on wild rice collection in Vietnam. In: G.L. Denning & Vo-Tong Xuan (eds.), Vietnam and IRRI: A partnership in rice research. International Rice Research Institute, Los Baños, Philippines, and Ministry of Agriculture and Food Industry, Hanoi, Vietnam, pp. 85-88.

Ford-Lloyd, B.V. & M.T. Jackson, 1984. Plant gene banks at risk. Nature 308, 683. [1]

Ford-Lloyd, B.V. & M.T. Jackson, 1990. Genetic resources refresher course embraces biotech. Biotechnology News No. 19, 7. University of Birmingham Biotechnology Management Group.

Jackson, M.T. (ed.), 1980. Investigación Agroeconómica para Optimizar la Productividad de la Papa. International Potato Center, Lima, Peru. Proceedings of the Regional Workshop held at Turrialba, Costa Rica, August 19-25, 1979.

Jackson, M.T., 1988. Biotechnology and the environment. Biotechnology News No. 15, 2. University of Birmingham Biotechnology Management Group.

Jackson, M.T., 1991. Global warming: the case for European cooperation for germplasm conservation and use. In: Th.J.L. van Hintum, L. Frese & P.M. Perret (eds.), Crop Networks. Searching for New Concepts for Collaborative Genetic Resources Management. International Crop Network Series No. 4. International Board for Plant Genetic Resources, Rome, Italy. Papers of the EUCARPIA/IBPGR symposium held in Wageningen, the Netherlands, December 3-6, 1990., pp. 125-131. PDF

Jackson, M.T., 1994. Preservation of rice strains. Nature 371, 470. [23]

Jackson, M.T. & J.A. Aguilar, 1979. Progresos en la adaptación de la papa a zonas cálidas. Memoria XXV Reunión PCCMCA, Honduras, Marzo 1979, Vol. IV, H16/1-10.

Jackson, M.T. & B.V. Ford-Lloyd, 1989. University of Birmingham holds international workshop on climate change and plant genetic resources. Diversity 5, 22-23.

Jackson, M.T. & B.V. Ford-Lloyd, 1990. University of Birmingham celebrates 20th anniversary of germplasm training course. Diversity 6, 11-12.

Jackson, M.T. & R.D. Huggan, 1993. Sharing the diversity of rice to feed the world. Diversity 9, 22-25. [45]

Jackson, M.T. & R.D. Huggan, 1996. Pflanzenvielfalt als Grundlage der Welternährung. Bulletin—das magazin der Schweizerische Kreditanstalt SKA. March/April 1996, 9-10.

Jackson, M.T., E.L. Javier & C.G. McLaren, 2000. Rice genetic resources for food security: four decades of sharing and use. In: W.G. Padolina (ed.), Plant Variety Protection for Rice in Developing Countries. Limited proceedings of the workshop on the Impact of Sui Generis Approaches to Plant Variety Protection in Developing Countries. February 16-18, 2000, IRRI, Los Baños, Philippines. International Rice Research Institute, Makati City, Philippines. pp. 3-8.

Jackson, M.T. & R.J.L. Lettington, 2003. Conservation and use of rice germplasm: an evolving paradigm under the International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture. In: Sustainable rice production for food security. Proceedings of the 20th Session of the International Rice Commission. Bangkok, Thailand, 23-26 July 2002.

http://www.fao.org/DOCREP/006/Y4751E/y4751e07.htm#bm07. Invited paper. PDF [24]

Jackson, M.T., G.C. Loresto & A.P. Alcantara, 1993. The International Rice Germplasm Center at IRRI. In: The Egyptian Society of Plant Breeding (1993). Crop Genetic Resources in Egypt: Present Status and Future Prospects. Papers of an ESPB Workshop, Giza, Egypt, March 2-3, 1992.

Jackson, M.T., J.L. Pham, H.J. Newbury, B.V. Ford-Lloyd & P.S. Virk, 1999. A core collection for rice—needs, opportunities and constraints. In: R.C. Johnson & T. Hodgkin (eds.), Core collections for today and tomorrow. International Plant Genetic Resources Institute, Rome, Italy, pp. 18-27. [25]

Jackson, M.T., L. Taylor & A.J. Thomson, 1985. Inbreeding and true potato seed production. In: Innovative Methods for Propagating Potatoes. Report of the XXVIII Planning Conference held at Lima, Peru, December 10-14, 1984, pp. 169-179. PDF [10]

Loresto, G.C. & M.T. Jackson, 1992. Rice germplasm conservation: a program of international collaboration. In: F. Cuevas-Pérez (ed.), Rice in Latin America: Improvement, Management, and Marketing. Proceedings of the VIII international rice conference for Latin America and the Caribbean, held in Villahermosa, Tabasco, Mexico, November 10-16, 1991. Centro Internacional de Agricultura Tropical, Cali, Colombia, pp. 61-65.

Loresto, G.C. & M.T. Jackson, 1996. South Asia partnerships forged to conserve rice genetic resources. Diversity 12, 60-61. [3]

Morin, S.R., J.L. Pham, M. Calibo, G. Abrigo, D. Erasga, M. Garcia, & M.T. Jackson, 1998. On farm conservation research: assessing rice diversity and indigenous technical knowledge. Invited paper presented at the Workshop on Participatory Plant Breeding, held in New Delhi, March 23-24, 1998.

Morin, S.R., J.L. Pham, M. Calibo, M. Garcia & M.T. Jackson, 1998. Catastrophes and genetic diversity: creating a model of interaction between genebanks and farmers. Paper presented at the FAO meeting on the Global Plan of Action on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture for the Asia-Pacific Region, held in Manila, Philippines, December 15-18, 1998.

Newbury, H.J., B.V. Ford-Lloyd, P.S. Virk, M.T. Jackson, M.D. Gale & J.-H. Zhu, 1996. Molecular markers and their use in organising plant germplasm collections. In: E.M. Young (ed.), Plant Sciences Research Programme Conference on Semi-Arid Systems. Proceedings of an ODA Plant Sciences Research Programme Conference , Manchester, UK, September 5-6, 1995, pp. 24-25.

Pham, J.L., M.R. Bellon & M.T. Jackson, 1996. A research program for on-farm conservation of rice genetic resources. International Rice Research Notes 21, 10-11. [8]

Pham, J.L., M.R. Bellon & M.T. Jackson, 1996. What is on-farm conservation research on rice genetic resources? In: J.T. Williams, C.H. Lamoureux & S.D. Sastrapradja (eds.), South East Asian Plant Genetic Resources. Proceedings of the Third South East Asian Regional Symposium on Genetic Resources, Serpong, Indonesia, August 22-24, 1995, pp. 54-65.

Rao, S.A, M.T. Jackson, V Phetpaseuth & C. Bounphanousay, 1997. Spontaneous interspecific hybrids in Oryza in the Lao PDR. International Rice Research Notes 22, 4-5. [5]

Virk, P.S., B.V. Ford-Lloyd, M.T. Jackson, H.S. Pooni, T.P. Clemeno & H.J. Newbury, 1996. Marker-assisted prediction of agronomic traits using diverse rice germplasm. In: International Rice Research Institute, Rice Genetics III. Proceedings of the Third International Rice Genetics Symposium, Manila, Philippines, October 16-20, 1995, pp. 307-316. [25]

CONFERENCE PAPERS AND POSTERS

Over the years I had the good fortune to attend scientific conferences around the world—a great opportunity to hear about the latest developments in one’s field of research, and also to network. For some conferences I contributed a paper or poster; at others, I was an invited speaker.

Alcantara, A.P., E.B. Guevarra & M.T. Jackson, 1999. The International Rice Genebank Collection Information System. Poster presented at the annual meeting of the Crop Science Society of America, Salt Lake City, October 31-November 4, 1999.

Appa Rao, S., C. Bounphanouxay, J.M. Schiller & M.T. Jackson, 1999. Collecting Rice Genetic Resources in the Lao PDR. Poster presented at the annual meeting of the Crop Science Society of America, Salt Lake City, October 31-November 4, 1999.

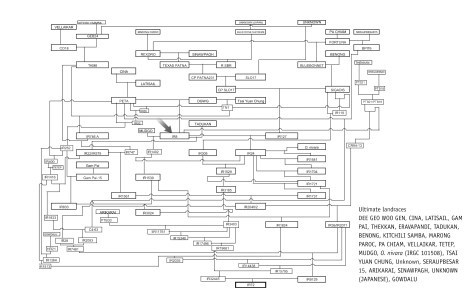

Cabanilla, V.R., M.T. Jackson & T.R. Hargrove, 1993. Tracing the ancestry of rice varieties. Poster presented at the 17th International Congress of Genetics, Birmingham, U.K., August 15-21, 1993. Volume of abstracts, 112-113.

Clugston, D.B. & M.T. Jackson, 1987. The application of embryo rescue techniques for the utilization of wild species in potato breeding. Paper presented at the Plant Breeding Section meeting of the Association of Applied Biologists, held at Churchill College, University of Cambridge, April 14-15, 1987.

Coleman, M., M. Jackson, S. Juned, B. Ford-Lloyd, J. Vessey & W. Powell, 1990. Interclonal genetic variability for in vitro response in Solanum tuberosum cv. Record. Paper presented at the 11th Triennial Conference of the European Association for Potato Research, Edinburgh, July 8-13, 1990.

Francisco-Ortega, F.J., M.T. Jackson, A. Santos-Guerra & M. Fernandez-Galvan, 1990. Ecogeographical variation in the Chamaecytisus proliferus complex in the Canary Islands. Paper presented at the Linnean Society Conference on Evolution and Conservation in the North Atlantic Islands, held at the Manchester Polytechnic, September 3-6, 1990.

Gubb, I.R., J.A. Callow, R.M. Faulks & M.T. Jackson, 1989. The biochemical basis for the lack of enzymic browning in the wild potato species Solanum hjertingii Hawkes. Am. Potato J. 66, 522 (abst.). Paper presented at the 73rd Annual Meeting of the Potato Association of America, Corvalis, Oregon, July 30 – August 3, 1989.

Hunt, E.D., M.T. Jackson, M. Oliva & A. Alcantara, 1993. Employing geographical information systems (GIS) for conserving and using rice germplasm. Poster presented at the 17th International Congress of Genetics, Birmingham, U.K., August 15-21, 1993. Volume of abstracts, 117.

Jackson, M.T., 1984. Variation patterns in Lathyrus sativus. Paper presented at the Second International Workshop on the Vicieae, held at the University of Southampton, February 15-16, 1984.

Jackson, M.T., 1993. Biotechnology and the conservation and use of plant genetic resources. Invited paper presented at the Workshop on Biotechnology in Developing Countries, held at the 17th International Congress of Genetics, Birmingham, U.K., August 15-21, 1993.

Jackson, M.T., 1994. Care for and use of biodiversity in rice. Invited paper presented at the Symposium on Food Security in Asia, held at the Royal Society, London, November 1, 1994.

Jackson, M.T., 1995. The international crop germplasm collections: seeds in the bank! Invited paper presented at the meeting Economic and Policy Research for Genetic Resources Conservation and Use: a Technical Consultation, held at IFPRI, Washington, D.C., June 21-22, 1995

Jackson, M.T., 1996. Intellectual property rights—the approach of the International Rice Research Institute. Invited paper presented at the Satellite Symposium on Biotechnology and Biodiversity: Scientific and Ethical Issues, held in New Delhi, India, November 15-16, 1996.

Jackson, M.T., 1999. Managing the world’s largest collection of rice genetic resources. In: J.N. Rutger, J.F. Robinson & R.H. Dilday (eds.), Proceedings of the International Symposium on Rice Germplasm Evaluation and Enhancement, held at the Dale Bumpers National Rice Research Center, Stuttgart, Arkansas, USA, August 30-September 2, 1998. Arkansas Agricultural Experiment Station Special Report 195. PDF [13]

Jackson, M.T., 1998. Intellectual property rights—the approach of the International Rice Research Institute. Invited paper at the Seminar-Workshop on Plant Patents in Asia Pacific, organized by the Asia & Pacific Seed Association (APSA), held in Manila, Philippines, September 21-22, 1998.

Jackson, M.T., 1998. Recent developments in IPR that have implications for the CGIAR. Invited paper presented at the ICLARM Science Day, International Center for Living Aquatic Resources Management, Manila, Philippines, September 30, 1998.

Jackson, M.T., 1998. The genetics of genetic conservation. Invited paper presented at the Fifth National Genetics Symposium, held at PhilRice, Nueva Ecija, Philippines, December 10-12, 1998.

Jackson, M.T., 1998. The role of the CGIAR’s System-wide Genetic Resources Programme (SGRP) in implementing the GPA. Invited paper presented at the Regional Meeting for Asia and the Pacific to facilitate and promote the implementation of the Global Plan of Action for the Conservation and Sustainable Use of Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture, held in Manila, Philippines, December 15-18, 1998.

Jackson, M.T., 2001. Collecting plant genetic resources: partnership or biopiracy. Invited paper presented at the annual meeting of the Crop Science Society of America, Charlotte, North Carolina, October 21-24, 2001.

Jackson, M.T., 2004. Achieving the UN Millennium Development Goals begins with rice research. Invited paper presented to the Cross Party International Development Group of the Scottish Parliament, Edinburgh, Scotland, June 2, 2004.

Jackson, M.T., 2001. Rice: diversity and livelihood for farmers in Asia. Invited paper presented in the symposium Cultural Heritage and Biodiversity, at the annual meeting of the Crop Science Society of America, Charlotte, North Carolina, October 21-24, 2001.

Jackson, M.T., A. Alcantara, E. Guevarra, M. Oliva, M. van den Berg, S. Erguiza, R. Gallego & M. Estor, 1995. Documentation and data management for rice genetic resources at IRRI. Paper presented at the Planning Meeting for the System-wide Information Network for Genetic Resources (SINGER), held at CIMMYT, Mexico, October 2-6, 1995.

Jackson, M.T. & L.C. González, 1979. Persistence of Pseudomonas solanacearum in an inceptisol in Costa Rica. In: CIP, Developments in the Control of Bacterial Diseases of Potato. Report of a Planning Conference held at CIP, LIma, Peru, 12-15 June 1979. pp. 66-71. [4]

Jackson, M.T. & L.C. González, 1979. Persistence of Pseudomonas solanacearum in an inceptisol in Costa Rica. Am. Potato J. 56, 467 (abst.). Paper presented at the 63rd Annual meeting of the Potato Association of America, Vancouver, British Columbia, July 22-27, 1979.

Jackson, M.T., F.C. de Guzman, R.A. Reaño, M.S.R. Almazan, A.P. Alcantara & E.B. Guevarra, 1999. Managing the world’s largest collection of rice genetic resources. Poster presented at the annual meeting of the Crop Science Society of America, Salt Lake City, October 31-November 4, 1999.

Jackson, M.T., E.L. Javier & C.G. McLaren, 1999. Rice genetic resources for food security. Invited paper at the IRRI Symposium, held at the annual meeting of the Crop Science Society of America, Salt Lake City, October 31-November 4, 1999.

Jackson, M.T. & G.C. Loresto, 1996. The role of the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) in supporting national and regional programs. Invited paper presented at the Asia-Pacific Consultation Meeting on Plant Genetic Resources, held in New Delhi, India, November 27-29, 1996.

Jackson, M.T., G.C. Loresto & F. de Guzman, 1996. Partnership for genetic conservation and use: the International Rice Genebank at the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI). Poster presented at the Beltsville Symposium XXI on Global Genetic Resources—Access, Ownership, and Intellectual Property Rights, held in Beltsville, Maryland, May 19-22, 1996.

Jackson, M.T., B.R. Lu, G.C. Loresto & F. de Guzman, 1995. The conservation of rice genetic resources at the International Rice Research Institute. Paper presented at the International Symposium on Research and Utilization of Crop Germplasm Resources held in Beijing, People’s Republic of China, June 1-3, 1995.

Jackson, M.T., B.R. Lu, M.S. Almazan, M.E. Naredo & A.B. Juliano, 2000. The wild species of rice: conservation and value for rice improvement. Poster presented at the annual meeting of the Crop Science Society of America, Minneapolis, November 5-9, 2000.

Jackson, M.T., P.R. Rowe & J.G. Hawkes, 1976. The enigma of triploid potatoes: a reappraisal. Am. Potato J. 53, 395 (abst.). Paper presented at the 60th Annual meeting of the Potato Association of America, University of Wisconsin—Stevens Point, July 26-29, 1976. [4]

Kameswara Rao, N. & M.T. Jackson, 1995. Seed production strategies for conservation of rice genetic resources. Poster presented at the Fifth International Workshop on Seeds, University of Reading, September 11-15, 1995.

Lu, B.R., A. Juliano, E. Naredo & M.T. Jackson, 1995. The conservation and study of wild Oryza species at the International Rice Research Institute. Paper presented at the International Symposium on Research and Utilization of Crop Germplasm Resources held in Beijing, People’s Republic of China, June 1-3, 1995.

Lu, B.R., M.E. Naredo, A.B. Juliano & M.T. Jackson, 1998. Biosystematic studies of the AA genome Oryza species (Poaceae). Poster presented at the Second International Conference on the Comparative Biology of the Monocotyledons and Third International Symposium on Grass Systematics and Evolution, Sydney, Australia, September 27-October 2, 1998.

Lu, B.R., M.E.B. Naredo, A.B. Juliano & M.T. Jackson, 2008. Genomic relationships of the AA genome Oryza species. In: G.S. Khush, D.S. Brar & B. Hardy (eds), Advances in Rice Genetics, Proceedings of the Fourth International Rice Genetics Symposium, Los Baños, Laguna, Philippines, 22-27 October 2000. pp. 118-121. [2]

Naredo, M.E., A.B. Juliano, M.S. Almazan, B.R. Lu & M.T. Jackson, 2000. Morphological and molecular diversity of AA genome species of rice. Poster presented at the annual meeting of the Crop Science Society of America, Minneapolis, November 5-9, 2000.

Newbury, H.J., P. Virk, M.T. Jackson, G. Bryan, M. Gale & B.V. Ford-Lloyd, 1993. Molecular markers and the analysis of diversity in rice. Poster presented at the 17th International Congress of Genetics, Birmingham, U.K., August 15-21, 1993. Volume of abstracts, 121-122.

Newton, E.L., R.A.C. Jones & M.T. Jackson, 1986. The serological detection of viruses of quarantine significance transmitted through true potato seed. Paper presented at the Virology Section meeting of the Association of Applied Biologists, held at the University of Warwick, September 29 – October 1, 1986.

Parsons, B.J., B.V. Ford-Lloyd, H.J. Newbury & M.T. Jackson, 1994. Use of PCR-based markers to assess genetic diversity in rice landraces from Bhutan and Bangladesh. Poster presented at the Annual Meeting of the British Ecological Society, held at The University of Birmingham, December 1994.

Pham, J.L., M.R. Bellon & M.T. Jackson, 1995. A research program on on-farm conservation of rice genetic resources. Poster presented at the Third International Rice Genetics Symposium, Manila, Philippines, October 16-20, 1995.

Pham J.L., S.R. Morin & M.T. Jackson, 2000. Linking genebanks and participatory conservation and management. Invited paper presented at the International Symposium on The Scientific Basis of Participatory Plant Breeding and Conservation of Genetic Resources, held at Oaxtepec, Morelos, Mexico, October 9-12, 2000.

Reaño, R., M.T. Jackson, F. de Guzman, S. Almazan & G.C. Loresto, 1995. The multiplication and regeneration of rice germplasm at the International Rice Genebank, IRRI. Paper presented at the Discussion Meeting on Regeneration Standards, held at ICRISAT, Hyderabad, India, December 4-7, 1995, sponsored by IPGRI, ICRISAT and FAO. [1]

Virk, P., B.V. Ford-Lloyd, M.T. Jackson & H.J. Newbury, 1994. The use of RAPD analysis for assessing diversity within rice germplasm. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the British Ecological Society, held at The University of Birmingham, December 1994.

Virk, P.S., H.J. Newbury, Y. Shen, M.T. Jackson & B.V. Ford-Lloyd, 1996. Prediction of agronomic traits in diverse germplasm of rice and beet using molecular markers. Paper presented at the Fourth International Plant Genome Conference, held in San Diego, California, January 14-18, 1996.

Watanabe, K., C. Arbizu, P. Schmiediche & M.T. Jackson, 1990. Germplasm enhancement methods for disomic tetraploid species of Solanum with special reference to S. acaule. Am. Potato J. 67, 586 (abst.). Paper presented at the 74th Annual meeting of the Potato Association of America, Quebec City, Canada, July 22-26, 1990. [4]

TECHNICAL PUBLICATIONS

Bryan, J.E., M.T. Jackson & N. Melendez, 1981. Rapid Multiplication Techniques for Potatoes. International Potato Center, Lima, Peru. PDF

Bryan, J.E., M.T. Jackson, M. Quevedo & N. Melendez, 1981. Single-Node Cuttings, a Rapid Multiplication Technique for Potatoes. CIP Slide Training Series, Guide Book I/2. International Potato Center, Lima, Peru. [25]

Bryan, J.E., N. Melendez & M.T. Jackson, 1981. Sprout Cuttings, a Rapid Multiplication Technique for Potatoes. CIP Slide Training Series, Guide Book I/1. International Potato Center, Lima, Peru. [2]

Bryan, J.E., N. Melendez & M.T. Jackson, 1981. Stem Cuttings, a Rapid Multiplication Technique for Potatoes. CIP Slide Training Series, Guide Book I/3. International Potato Center, Lima, Peru. [63]

Catty, J.P. & M.T. Jackson, 1989. Starch Gel Electrophoresis of Isozymes – A Laboratory Manual, Second edition. School of Biological Sciences, University of Birmingham.

Quevedo, M., J.E. Bryan, M.T. Jackson & N. Melendez, 1981. Leaf-Bud Cuttings, a Rapid Multiplication Technique for Potatoes. CIP Slide Training Series – Guide Book I/4. International Potato Center, Lima, Peru. [2]

BOOK REVIEWS

Jackson, M.T., 1983. Outlook on Agriculture 12, 205. Dictionary of Cultivated Plants and Their Regions of Diversity, by A.C. Zeven & J.M.J. de Wet, 1982. Pudoc, Wageningen.

Jackson, M.T., 1985. Outlook on Agriculture 14, 50. 1983 Rice Germplasm Conservation Workshop. IRRI and IBPGR, 1983. Manila.

Jackson, M.T., 1986. Journal of Applied Ecology 23, 726-727. The Value of Conserving Genetic Resources, by Margery L. Oldfield, 1984. US Dept. of the Interior, Washington, DC.

Jackson, M.T., 1989. Phytochemistry 28, 1783. World Crops: Cool Season Food Legumes, edit. by R.J. Summerfield, 1988. Martinus Nijhoff Publ.

Jackson, M.T., 1989. Plant, Cell & Environment 12, 589-590. Genetic Resources of Phaseolus Beans, edit. by P. Gepts, 1988. Martinus Nijhoff Publ.

Jackson, M.T., 1989. Heredity 64, 430-431. Genetic Resources of Phaseolus Beans, edit. by P. Gepts, 1988. Martinus Nijhoff Publ.

Jackson, M.T., 1989. Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society 102, 88-91. Seeds and Sovereignty, edit. by J.R. Kloppenburg, 1988. Duke University Press.

Jackson, M.T., 1989. Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society 100, 285-286. Conserving the Wild Relatives of Crops, by E. Hoyt, 1988. IBPGR/IUCN/WWF.

Jackson, M.T., 1989. Annals of Botany 64, 606-608. The Potatoes of Bolivia – Their Breeding Value and Evolutionary Relationships, by J.G. Hawkes & J.P. Hjerting, Oxford Scientific Publications.

Jackson, M.T., 1991. Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society 107, 102-104. Grain Legumes – Evolution and Genetic Resources, by J. Smartt, 1990, Cambridge University Press.

Jackson, M.T., 1991. Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society 107, 104-107. Plant Population Genetics, Breeding, and Genetic Resources, edit. by A.H.D. Brown, M.T. Clegg, A.L. Kahler & B.S. Weir, 1990, Sinauer Associates Inc.

Jackson, M.T., 1991. Field Crops Research 26, 77-79. The Use of Plant Genetic Resources, ed. by A.H.D. Brown, O.H. Frankel, D.R. Marshall & J.T. Williams, 1989, Cambridge University Press.

Jackson, M.T., 1991. Annals of Botany 67, 367-368. Isozymes in Plant Biology, edit. by D.E. Soltis & P.S. Soltis, 1990, Chapman and Hall.

Jackson, M.T., 1991. The Biologist 38, 154-155. The Molecular and Cellular Biology of the Potato, edit. by M.E. Vayda & W.D. Park, 1990, C.A.B. International.

Jackson, M.T., 1992. Diversity 8, 36-37. Biotechnology and the Future of World Agriculture, by H. Hobbelink, 1991, Zed Books Ltd.

Jackson, M.T., 1997. Experimental Agriculture 33, 386. Biodiversity and Agricultural Intensification: Partners for Development and Conservation, edit. by J.P. Srivastava, N.J.H. Smith & D.A. Forno, 1996. Environmentally Sustainable Development Studies and Monographs Series No. 11, The World Bank, Washington, D.C.

Jackson, M.T., 2001. Annals of Botany 88, 332-333. Broadening the genetic base of crop production, edit. By Cooper H.D., C. Spillane & T. Hodgkin, 2001. Wallingford: CAB International with FAO and IPGRI, Rome.

CONSULTANCY REPORT

CGIAR-IEA, 2017. Evaluation of CGIAR research support program for Managing and Sustaining Crop Collections. Rome, Italy: Independent Evaluation Arrangement (IEA) of CGIAR. Authored by M.T. Jackson, M.J. Borja Tome & B.V. Ford-Lloyd. [2]

OBITUARIES

Joe Smartt

Jack Hawkes

Trevor Williams

Jackson, M.T., 2011. John Gregory Hawkes (1915–2007). Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/99090. PDF

Jackson, M.T., 2013. Dr. Joseph Smartt (1931-2013). Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution 60, 1921-1922. PDF

Jackson, M.T. & N. Murthi Anishetty, 2015. John Trevor Williams (1938 – 2015). Indian Journal of Plant Genetic Resources 28, 161-162. PDF

Jackson, M.T., 2015. J Trevor Williams (1938–2015): IBPGR director and genetic conservation pioneer. Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution 62, 809–813. PDF

Jackson, M.T., 2023. Sheehy, John Edward (1942-2019). Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/odnb/9780198614128.013.90000380930. PDF.

Jackson, M.T., 2024. Williams, (John) Trevor (1938-2015). Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/odnb/9780198614128.013.90000382511. PDF.

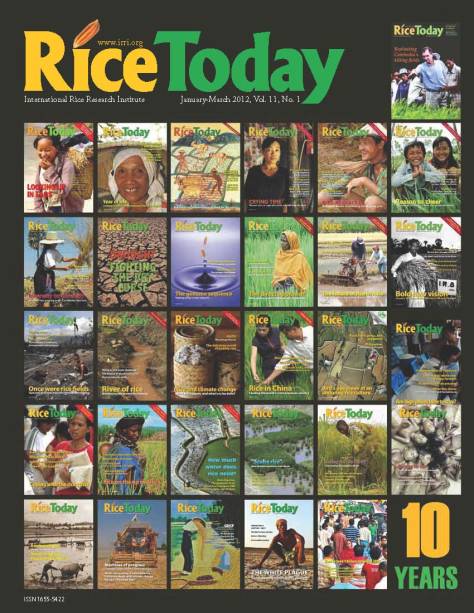

Rice is such a fascinating crop you might want to understand a little more. And there’s no better source than Rice Today, a magazine launched by the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) in 2002, and published quarterly ever since. It’s a solid mix of rice news and research, stories about rice agriculture from around the world, rice recipes even, and the odd children’s story about rice.

Rice is such a fascinating crop you might want to understand a little more. And there’s no better source than Rice Today, a magazine launched by the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) in 2002, and published quarterly ever since. It’s a solid mix of rice news and research, stories about rice agriculture from around the world, rice recipes even, and the odd children’s story about rice.

Rice Today is published by IRRI on behalf of Rice (GRiSP), the CGIAR research program on rice; it is also available online. Lanie Reyes (right) joined IRRI in 2008 as a science writer and editor. She is now editor-in-chief. She is supported by Savitri Mohapatra and Neil Palmer from sister centers Africa Rice Center in Côte d’Ivoire and CIAT in Colombia, respectively.

Rice Today is published by IRRI on behalf of Rice (GRiSP), the CGIAR research program on rice; it is also available online. Lanie Reyes (right) joined IRRI in 2008 as a science writer and editor. She is now editor-in-chief. She is supported by Savitri Mohapatra and Neil Palmer from sister centers Africa Rice Center in Côte d’Ivoire and CIAT in Colombia, respectively.

I am leading the evaluation of an international genebanks program, part of the portfolio of the

I am leading the evaluation of an international genebanks program, part of the portfolio of the

Springer now has its own in-house genetic resources journal, Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution (I’m a member of the editorial board), but there are others such as Plant Genetic Resources – Characterization and Utilization (published by Cambridge University Press). Nowadays there are more journals to choose from dealing with disciplines like seed physiology, molecular systematics and ecology, among others, in which papers on genetic resources can find a home.

Springer now has its own in-house genetic resources journal, Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution (I’m a member of the editorial board), but there are others such as Plant Genetic Resources – Characterization and Utilization (published by Cambridge University Press). Nowadays there are more journals to choose from dealing with disciplines like seed physiology, molecular systematics and ecology, among others, in which papers on genetic resources can find a home.

And it wasn’t long before his presence was felt. It’s not inappropriate to comment that IRRI had lost its way during the previous decade for various reasons. There was no clear research strategy nor direction. Strong leadership was in short supply. Bob soon put an end to that, convening an international expert group of stakeholders (rice researchers, rice research leaders from national programs, and donors) to help the institute chart a perspective for the next decade or so. In 2006 IRRI’s Strategic Plan (2007-2015),

And it wasn’t long before his presence was felt. It’s not inappropriate to comment that IRRI had lost its way during the previous decade for various reasons. There was no clear research strategy nor direction. Strong leadership was in short supply. Bob soon put an end to that, convening an international expert group of stakeholders (rice researchers, rice research leaders from national programs, and donors) to help the institute chart a perspective for the next decade or so. In 2006 IRRI’s Strategic Plan (2007-2015),

Many examples are highlighted in a recent article,

Many examples are highlighted in a recent article,

I expect you are familiar with the logo of the 4th International Rice Congress (IRC2014 – at left) that was held in Bangkok at the end of October last year.

I expect you are familiar with the logo of the 4th International Rice Congress (IRC2014 – at left) that was held in Bangkok at the end of October last year.

What about identical monozygotic twins, such as

What about identical monozygotic twins, such as

and the CGIAR

and the CGIAR

Ron Cantrell, IRRI’s Director General in 2002 asked me to organize IRRI Day. But what to organize and who to involve? We decided very early on that, as much as possible, to show our visitors rice growing in the field, but with some laboratory stops where appropriate or indeed feasible, taking into account the logistics of moving a large number of people through relatively confined spaces.

Ron Cantrell, IRRI’s Director General in 2002 asked me to organize IRRI Day. But what to organize and who to involve? We decided very early on that, as much as possible, to show our visitors rice growing in the field, but with some laboratory stops where appropriate or indeed feasible, taking into account the logistics of moving a large number of people through relatively confined spaces.