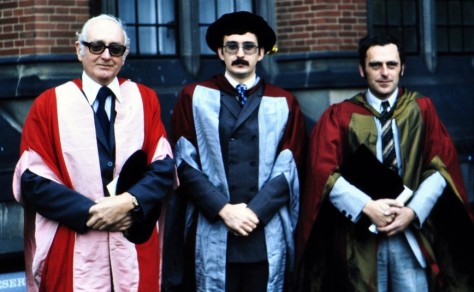

My decision to leave a tenured position at the University of Birmingham in June 1991 was not made lightly. I was about to be promoted to Senior Lecturer, and I’d found my ‘home’ in the Plant Genetics Research Group following the reorganization of the School of Biological Sciences a couple of years earlier.

My decision to leave a tenured position at the University of Birmingham in June 1991 was not made lightly. I was about to be promoted to Senior Lecturer, and I’d found my ‘home’ in the Plant Genetics Research Group following the reorganization of the School of Biological Sciences a couple of years earlier.

But I wasn’t particularly happy. Towards the end of the 1980s, Margaret Thatcher’s Conservative Government had become hostile to the university sector, demanding significant changes in the way they operated before acceding to any improvements in pay and conditions. Some of the changes then forced on the university system still bedevil it to this day.

I felt as though I was treading water, trying to keep my head above the surface. I had a significant teaching load, research was ticking along, PhD and MSc students were moving through the system, but still the university demanded more. So when an announcement of a new position as Head of the Genetic Resources Center (GRC) at the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) in the Philippines landed on my desk in September 1990, it certainly caught my interest. I discussed such a potential momentous change with Steph, and with a couple of colleagues at the university.

I felt as though I was treading water, trying to keep my head above the surface. I had a significant teaching load, research was ticking along, PhD and MSc students were moving through the system, but still the university demanded more. So when an announcement of a new position as Head of the Genetic Resources Center (GRC) at the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) in the Philippines landed on my desk in September 1990, it certainly caught my interest. I discussed such a potential momentous change with Steph, and with a couple of colleagues at the university.

Nothing venture, nothing gained, I formally submitted an application to IRRI and, as they say, the rest is history. However, I never expected to spend the next 19 years in the Philippines.

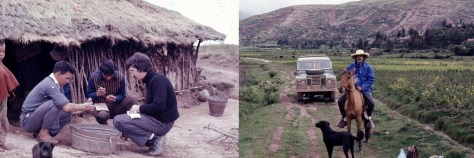

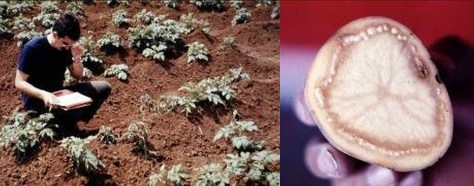

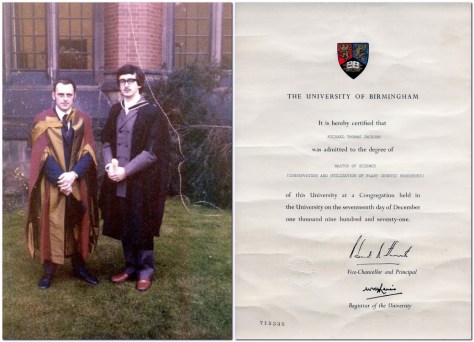

Since 1971, I’d worked almost full time in various aspects of conservation and use of plant genetic resources. I’d collected potato germplasm in Peru and the Canary Islands while at Birmingham, learned the basics of potato agronomy and production, worked alongside farmers, helped train the next generation of genetic conservation specialists, and was familiar with the network of international agricultural research centers supported through the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research or CGIAR.

What I had never done was manage a genebank or headed a department with tens of staff at all professional levels. Because the position in at IRRI involved both of these. The head would be expected to provide strategic leadership for GRC and its three component units: the International Rice Germplasm Center (IRGC), the genebank; the International Network for the Genetic Evaluation of Rice (INGER); and the Seed Health Unit (SHU). However, only the genebank would be under the day-to-day management of the GRC head. Both INGER and the SHU would be managed by project leaders, while being amalgamated into a single organizational unit, the Genetic Resources Center.

I was unable to join IRRI before 1 July 1991 due to teaching and examination commitments at the university that I was obliged to fulfill. Nevertheless, in April I represented IRRI at an important genetic resources meeting at FAO in Rome, where I first met the incoming Director General of the International Board for Plant Genetic Resources (soon to become the International Plant Genetic Resources Institute or IPGRI), Dr Geoff Hawtin, with whom I’ve retained a friendship ever since.

On arrival at IRRI, I discovered that the SHU had been removed from GRC, a wise decision in my opinion, but not driven I eventually discerned by real ‘conflict of interest’ concerns, rather internal politics. However, given that the SHU was (and is) responsible, in coordination with the Philippines plant health authorities, to monitor all imports and exports of rice seeds at IRRI, it seemed prudential to me not to be seen as both ‘gamekeeper and poacher’, to coin a phrase. After all the daily business of the IRGC and INGER was movement of healthy seeds across borders.

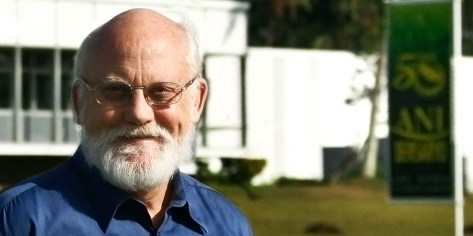

Klaus Lampe

My focus was on the genebank, its management and role within an institute that itself was undergoing some significant changes, 30 years after it had been founded, under its fifth Director General, Dr Klaus Lampe, who had hired me. He made it clear that the head of GRC would not only be expected to bring IRGC and INGER effectively into a single organizational unit, but also complete a ‘root and branch’ overhaul of the genebank’s operations and procedures, long overdue.

Since INGER had its own leader, an experienced rice breeder Dr DV Seshu, somewhat older than myself, I could leave the running of that network in his hands, and only concern myself with INGER within the context of the new GRC structure and personnel policies. Life was not easy. My INGER colleagues dragged their feet, and had to be ‘encouraged’ to accept the new GRC reality that reduced the freewheeling autonomy they had become accustomed to over the previous 20 years or so, on a budget of about USD1 million a year provided by the United Nations Development Program or UNDP.

When interviewing for the GRC position I had also queried why no germplasm research component had been considered as part of the job description. I made it clear that if I was considered for the position, I would expect to develop a research program on rice genetic resources. That indeed became the situation.

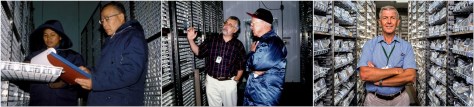

Once in post at IRRI, I asked lots of questions. For at least six months until the end of 1991, I made no decisions about changes in direction for the genebank until I better understood how it operated and what constraints it faced. I also had to size up the caliber of staff, and develop a plan for further staff recruitment. I did persuade IRRI management to increase resource allocation to the genebank, and we were then able to hire technical staff to support many time critical areas.

Once in post at IRRI, I asked lots of questions. For at least six months until the end of 1991, I made no decisions about changes in direction for the genebank until I better understood how it operated and what constraints it faced. I also had to size up the caliber of staff, and develop a plan for further staff recruitment. I did persuade IRRI management to increase resource allocation to the genebank, and we were then able to hire technical staff to support many time critical areas.

But one easy decision I did make early on was to change the name of the genebank. As I’ve already mentioned, its name was the ‘International Rice Germplasm Center’, but it didn’t seem logical to place one center within another, IRGC in GRC. So we changed its name to the ‘International Rice Genebank’, while retaining the acronym IRGC (which was used for all accessions in the germplasm collection) to refer to International Rice Genebank Collection.

In various blog posts over the past year or so, I have written extensively about the genebank at IRRI, so I shall not repeat those details here, but provide a summary only.

I realized very quickly that each staff member had to have specific responsibilities and accountability. We needed a team of mutually-supportive professionals. In a recent email from one of my staff, he mentioned that the genebank today was reaping the harvest of the ‘seeds I’d sown’ 25 years ago. But, as I replied, one has to have good seeds to begin with. And the GRC staff were (and are) in my opinion quite exceptional.

In terms of seed management, we beefed up the procedures to regenerate and dry seeds, developed protocols for routine seed viability testing, and eliminated duplicate samples of genebank accessions that were stored in different locations, establishing an Active Collection (at +4ºC, or thereabouts) and a Base Collection (held at -18ºC). Pola de Guzman was made Genebank Manager, and Ato Reaño took responsibility for all field operations. Our aim was not only to improve the quality of seed being conserved in the genebank, but also to eliminate (in the shortest time possible) the large backlog of samples to be processed and added to the collection.

Dr Kameswara Rao (from IRRI’s sister center ICRISAT, based in Hyderabad, India) joined GRC to work on the relationship between seed quality and seed growing environment. He had received his PhD from the University of Reading, and this research had started as a collaboration with Professor Richard Ellis there. Rao’s work led to some significant changes to our seed production protocols.

Dr Kameswara Rao (from IRRI’s sister center ICRISAT, based in Hyderabad, India) joined GRC to work on the relationship between seed quality and seed growing environment. He had received his PhD from the University of Reading, and this research had started as a collaboration with Professor Richard Ellis there. Rao’s work led to some significant changes to our seed production protocols.

Since I retired, I have been impressed to see how research on seed physiology and conservation, led by Dr Fiona Hay (now at Aarhus University in Denmark) has moved on yet again. Take a look at this story I posted in 2015.

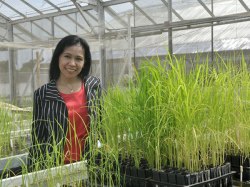

Screen house space for the valuable wild species collection was doubled, and Soccie Almazan appointed as wild species curator.

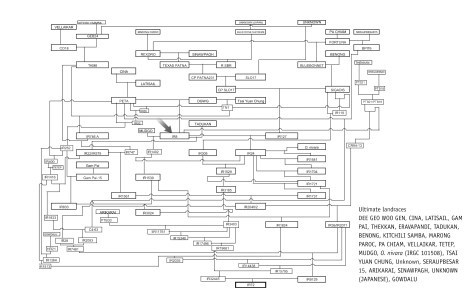

One of the most critical issues I had to address was data management, which was in quite a chaotic state, with data on the Asian rice samples (known as Oryza sativa), the African rices (O. glaberrima), and the remaining 20+ wild species managed in separate databases that could not ‘talk’ to each another. We needed a unified data system, handling all aspects of genebank management, germplasm regeneration, characterization and evaluation, and germplasm exchange. We spent about three years building that system, the International Rice Genebank Collection Information System (IRGCIS). It was complicated because data had been coded differently for the two cultivated and wild species, that I have written about here. That’s a genebank lesson that needs to be better appreciated in the genebank community. My colleagues Adel Alcantara, Vanji Guevarra, and Myrna Oliva did a splendid job, which was methodical and thorough.

In 1995 we released the first edition of a genebank operations manual for the International Rice Genebank, something that other genebanks have only recently got round to.

Our germplasm research focused on four areas:

- seed conservation (with Richard Ellis at the University of Reading, among others);

- the use of molecular markers to better manage and use the rice collection (with colleagues at the University of Birmingham and the John Innes Centre in Norwich);

- biosystematics of rice, concentrating on the closest wild relative species (led by Dr Bao-Rong Lu and supported by Yvette Naredo and the late Amy Juliano);

- on farm conservation – a project led by French geneticist Dr Jean-Louis Pham and social anthropologists Dr Mauricio Bellon and Steve Morin.

At the beginning of the 1990s there were no genome data to support the molecular characterization of rice. Our work with molecular markers was among use these to study a germplasm collection. The research we published on association analysis is probably the first paper that showed this relationship between markers and morphological characteristics or traits.

In 1994, I developed a 5-year project proposal for almost USD3.3 million that we submitted for support to the Swiss Development Cooperation. The three project components included:

In 1994, I developed a 5-year project proposal for almost USD3.3 million that we submitted for support to the Swiss Development Cooperation. The three project components included:

- germplasm exploration (165 collecting missions in 22 countries), with about half of the germplasm collected in Laos; most of the collected germplasm was duplicated at that time in the International Rice Genebank;

- training: 48 courses or on-the-job opportunities between 1995 and 1999 in 14 countries or at IRRI in Los Baños, for more than 670 national program staff;

- on farm conservation to:

-

to increase knowledge on farmers’ management of rice diversity, the factors thatinfluence it, and its genetic implications;

-

to identify strategies to involve farmers’ managed systems in the overall conservation ofrice genetic resources.

-

I was ably assisted in the day-to-day management of the project by my colleague Eves Loresto, a long-time employee at IRRI who sadly passed away a few years back.

When I joined IRRI in 1991 there were just under 79,000 rice samples in the genebank. Through the Swiss-funded project we increased the collection by more than 30%. Since I left the genebank in 2001 that number has increased to over 136,000 making it the largest collection of rice germplasm in the world.

We conducted training courses in many countries in Asia and Africa. The on-farm research was based in the Philippines, Vietnam, and eastern India. It was one of the first projects to bring together a population geneticist and a social anthropologist working side-by-side to understand how, why, and when farmers grew different rice varieties, and what incentives (if any) would induce them to continue to grow them.

The final report of this 5-year project can be read here. We released the report in 2000 on an interactive CD-ROM, including almost 1000 images taken at many of the project sites, training courses, or during germplasm exploration. However, the links in the report are not active on this blog.

During my 10 year tenure of GRC, I authored/coauthored 33 research papers on various aspects of rice genetic resources, 1 co-edited book, 14 book chapters, and 23 papers in the so-called ‘grey’ literature, as well as making 33 conference presentations. Check out all the details in this longer list, and there are links to PDF files for many of the publications.

In 1993 I was elected chair of the Inter-Center Working Group on Genetic Resources, and worked closely with Geoff Hawtin at IPGRI, and his deputy Masa Iwanaga (an old colleague from CIP), to develop the CGIAR’s System-wide Genetic Resources Program or SGRP. Under the auspices of the SGRP I organized a workshop in 1999 on the application of comparative genetics to genebank collections.

Professor John Barton

With the late John Barton, Professor of Law at Stanford University, we developed IRRI’s first policy on intellectual property rights focusing on the management, exchange and use of rice genetic resources. This was later expanded into a policy document covering all aspects of IRRI’s research.

The 1990s were a busy decade, germplasm-wise, at IRRI and in the wider genetic resources community. The Convention on Biological Diversity had come into force in 1993, and many countries were enacting their own legislation (such as Executive Order 247 in the Philippines in 1995) governing access to and use sovereign genetic resources. It’s remarkable therefore that we were able to accomplish so much collecting between 1995 and 2000, and that national programs had trust in the IRG to safely conserve duplicate samples from national collections.

Ron Cantrell

All good things come to an end, and in January 2001 I was asked by then Director General Ron Cantrell to leave GRC and become the institute’s Director for Program Planning and Coordination (that became Communications two years later as I took on line management responsibility for Communication and Publications Services, IT, and the library). On 30 April, I said ‘goodbye’ to my GRC colleagues to move to my new office across the IRRI campus, although I kept a watching brief over GRC for the next year until my successor, Dr Ruaraidh Sackville Hamilton, arrived in Los Baños.

Listen to Ruaraidh and his staff talking about the genebank.

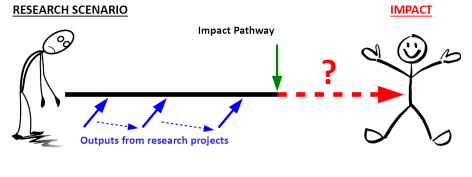

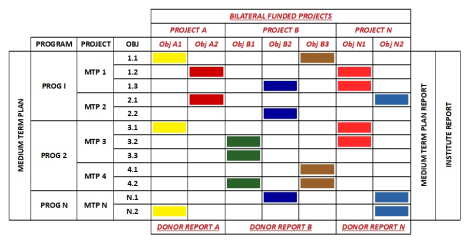

So, after a decade with GRC I moved into IRRI’s senior management team and set about bringing a modicum of rationale to the institute’s resource mobilization initiatives, and management of its overall research project portfolio. I described here how it all started. The staff I was able to recruit were outstanding. Running DPPC was a bit like running a genebank: there were many individual processes and procedures to manage the various research projects, report back to donors, submit grant proposals and the like. Research projects were like ‘genebank accessions’ – all tied together by an efficient data management system that we built in an initiative led by Eric Clutario (seen standing on the left below next to me).

From my DPPC vantage point, it was interesting to watch Ruaraidh take GRC to the next level, adding a new cold storage room, and using bar-coding to label all seed packets, a great addition to the data management effort. With Ken McNally’s genomics research, IRRI has been at the forefront of studies to explore the diversity of genetic diversity in germplasm collections.

Last October, the International Rice Genebank was the first to receive in-perpetuity funding from the Crop Trust. I’d like to think that the significant changes we made in the 1990s to the genebank and management of rice germplasm kept IRRI ahead of the curve, and contributed to its selection for this funding.

I completed a few publications during this period, and finally retired from IRRI at the end of April 2010. Since retirement I have co-edited a second book on climate change and genetic resources, led a review of the CGIAR’s genebank program, and was honored by HM The Queen as an Officer of the British Empire (OBE) in 2012 for my work at IRRI.

So, as 2018 draws to a close, I can look back on almost 50 years involvement in the conservation and use of plant genetic resources for food and agriculture. What an interesting—and fulfilling—journey it has been.

- Discovering Vavilov, and building a career in plant genetic resources: (1) Starting out in South America in the 1970s

- Discovering Vavilov, and building a career in plant genetic resources: (2) Training the next generation of specialists in the 1980s

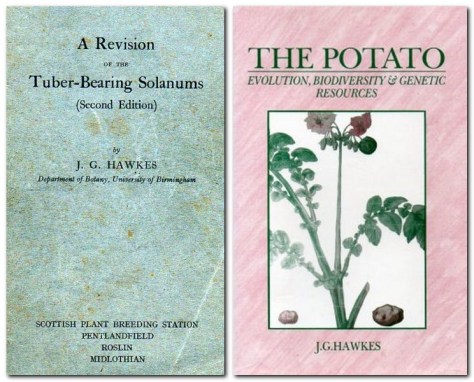

At the same time I was equally influenced by my mentor and PhD supervisor

At the same time I was equally influenced by my mentor and PhD supervisor  I embarked on a career in international agricultural research for development almost by serendipity. One year became a lifetime. The conservation and use of plant genetic resources became the focus of my work in two international agricultural research centers (CIP and IRRI) of the

I embarked on a career in international agricultural research for development almost by serendipity. One year became a lifetime. The conservation and use of plant genetic resources became the focus of my work in two international agricultural research centers (CIP and IRRI) of the

I was searching YouTube the other day for videos about the recent 5th International Rice Congress held in Singapore, when I came across several on the

I was searching YouTube the other day for videos about the recent 5th International Rice Congress held in Singapore, when I came across several on the

materials, among others. You can check the status of the IRRI collection (and many more genebanks in the

materials, among others. You can check the status of the IRRI collection (and many more genebanks in the

In 1981, one of the students attending the one-year

In 1981, one of the students attending the one-year  Today, the

Today, the  All four centers are members of the

All four centers are members of the

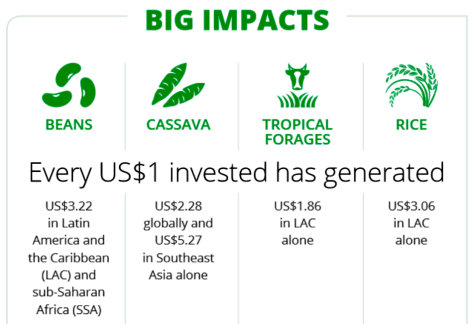

In 1969, World Bank President Robert McNamara (who had been US Secretary of Defense under Presidents Kennedy and Johnson) wrote to the heads of the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) in Rome and the United Nations Development Fund (UNDP) in New York saying: I am writing to propose that the FAO, the UNDP and the World Bank jointly undertake to organize a long-term program of support for regional agricultural research institutes. I have in mind support not only for some of the existing institutes, including the four now being supported by the Ford and Rockefeller Foundations [IRRI, CIMMYT, IITA, and CIAT], but also, as occasion permits, for a number of new ones.

In 1969, World Bank President Robert McNamara (who had been US Secretary of Defense under Presidents Kennedy and Johnson) wrote to the heads of the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) in Rome and the United Nations Development Fund (UNDP) in New York saying: I am writing to propose that the FAO, the UNDP and the World Bank jointly undertake to organize a long-term program of support for regional agricultural research institutes. I have in mind support not only for some of the existing institutes, including the four now being supported by the Ford and Rockefeller Foundations [IRRI, CIMMYT, IITA, and CIAT], but also, as occasion permits, for a number of new ones.

And that’s how I got into research management in 2001, when IRRI Director General Ron Cantrell invited me to join the senior management team as

And that’s how I got into research management in 2001, when IRRI Director General Ron Cantrell invited me to join the senior management team as

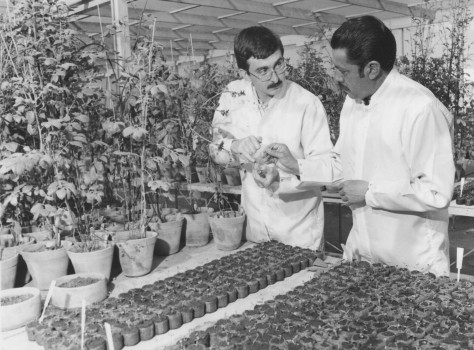

Soccie Almazan became the curator of the wild rices that had to be grown in a quarantine screenhouse some distance from the main research facilities, on the far side of the experiment station. But the one big change that we made was to incorporate all the germplasm types, cultivated or wild, into a single genebank collection, rather than the three collections. Soccie brought about some major changes in how the wild species were handled, and with an expansion of the screenhouses in the early 1990s (as part of the overall refurbishment of institute infrastructure) the genebank at last had the space to adequately grow (in pots) all this valuable germplasm that required special attention. See the video from 4:30. Soccie retired from IRRI in the last couple of years.

Soccie Almazan became the curator of the wild rices that had to be grown in a quarantine screenhouse some distance from the main research facilities, on the far side of the experiment station. But the one big change that we made was to incorporate all the germplasm types, cultivated or wild, into a single genebank collection, rather than the three collections. Soccie brought about some major changes in how the wild species were handled, and with an expansion of the screenhouses in the early 1990s (as part of the overall refurbishment of institute infrastructure) the genebank at last had the space to adequately grow (in pots) all this valuable germplasm that required special attention. See the video from 4:30. Soccie retired from IRRI in the last couple of years.

We also had to choose a short research project, mostly carried out during the summer months through the end of August, and written up and presented for examination in September. While the bulk of the work was carried out following the exams, I think all of us had started on some aspects much earlier in the academic year. In my case, for example, I had chosen a topic on lentil evolution by November 1970, and began to assemble a collection of seeds of different varieties. These were planted (under cloches) in the field by the end of March 1971, so that they were flowering by June. I also made chromosome counts on each accession in my spare time from November onwards, on which my very first

We also had to choose a short research project, mostly carried out during the summer months through the end of August, and written up and presented for examination in September. While the bulk of the work was carried out following the exams, I think all of us had started on some aspects much earlier in the academic year. In my case, for example, I had chosen a topic on lentil evolution by November 1970, and began to assemble a collection of seeds of different varieties. These were planted (under cloches) in the field by the end of March 1971, so that they were flowering by June. I also made chromosome counts on each accession in my spare time from November onwards, on which my very first  At the end of the course, all our work, exams and dissertation, was assessed by an external examiner (a system that is commonly used among universities in the UK). The examiner was

At the end of the course, all our work, exams and dissertation, was assessed by an external examiner (a system that is commonly used among universities in the UK). The examiner was

Ayla came to Birmingham with a clear focus on what she wanted to achieve. She saw the MSc course as the first step to completing her PhD, and even arrived in Birmingham with samples of seeds for her research. During the course she completed a dissertation (with Jack Hawkes) on the origin of rye (Secale cereale), and she continued this project for a further two years or so for her PhD. I don’t recall whether she had the MSc conferred or not. In those days, it was not unusual for someone to convert an MSc course into the first year of a doctoral program; I’m pretty sure this is what Ayla did.

Ayla came to Birmingham with a clear focus on what she wanted to achieve. She saw the MSc course as the first step to completing her PhD, and even arrived in Birmingham with samples of seeds for her research. During the course she completed a dissertation (with Jack Hawkes) on the origin of rye (Secale cereale), and she continued this project for a further two years or so for her PhD. I don’t recall whether she had the MSc conferred or not. In those days, it was not unusual for someone to convert an MSc course into the first year of a doctoral program; I’m pretty sure this is what Ayla did.

Folu married shortly before traveling to Birmingham. Her husband had enrolled for a PhD at University College London. He had seen a small poster about the MSc course at Birmingham on a notice board at the University of Ibadan, Nigeria where Folu had completed her BSc in Botany. She applied successfully for financial support from the Mid-Western Nigeria Government to attend the MSc course, and subsequently her PhD studies.

Folu married shortly before traveling to Birmingham. Her husband had enrolled for a PhD at University College London. He had seen a small poster about the MSc course at Birmingham on a notice board at the University of Ibadan, Nigeria where Folu had completed her BSc in Botany. She applied successfully for financial support from the Mid-Western Nigeria Government to attend the MSc course, and subsequently her PhD studies.

genetic resources the training courses she helped deliver, and the research linkages she promoted among various bodies in Nigeria. She has

genetic resources the training courses she helped deliver, and the research linkages she promoted among various bodies in Nigeria. She has

The first week of October 1967. 50 years ago, to the day and date. Monday 2 October.

The first week of October 1967. 50 years ago, to the day and date. Monday 2 October.

I had a room on the sixth floor, with a view overlooking Woodmill Lane to the west, towards the university, approximately 1.2 miles and 25 minutes away on foot. In the next room to mine, or perhaps two doors away, I met John Grainger who was also signed up for the same course as me. John had grown up in Kenya where his father worked as an entomologist. Now that sounded quite exotic to me.

I had a room on the sixth floor, with a view overlooking Woodmill Lane to the west, towards the university, approximately 1.2 miles and 25 minutes away on foot. In the next room to mine, or perhaps two doors away, I met John Grainger who was also signed up for the same course as me. John had grown up in Kenya where his father worked as an entomologist. Now that sounded quite exotic to me.

Rice is such a fascinating crop you might want to understand a little more. And there’s no better source than Rice Today, a magazine launched by the

Rice is such a fascinating crop you might want to understand a little more. And there’s no better source than Rice Today, a magazine launched by the

And it wasn’t long before his presence was felt. It’s not inappropriate to comment that IRRI had lost its way during the previous decade for various reasons. There was no clear research strategy nor direction. Strong leadership was in short supply. Bob soon put an end to that, convening an international expert group of stakeholders (rice researchers, rice research leaders from national programs, and donors) to help the institute chart a perspective for the next decade or so. In 2006 IRRI’s Strategic Plan (2007-2015),

And it wasn’t long before his presence was felt. It’s not inappropriate to comment that IRRI had lost its way during the previous decade for various reasons. There was no clear research strategy nor direction. Strong leadership was in short supply. Bob soon put an end to that, convening an international expert group of stakeholders (rice researchers, rice research leaders from national programs, and donors) to help the institute chart a perspective for the next decade or so. In 2006 IRRI’s Strategic Plan (2007-2015),

What about identical monozygotic twins, such as

What about identical monozygotic twins, such as