A few days ago, I wrote a piece about perceived or real threats to the UK’s development aid budget. I am very concerned that among politicians and the wider general public there is actually little understanding about the aims of international development aid, how it’s spent, what it has achieved, and even how it’s accounted for.

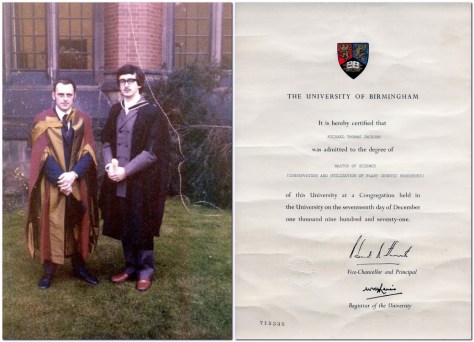

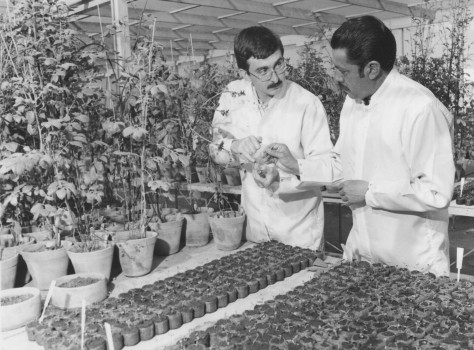

Throughout my career, I worked for organizations and programs that were supported from international development aid budgets. Even during the decade I was a faculty member at The University of Birmingham during the 1980s, I managed a research project on potatoes (a collaboration with the International Potato Center, or CIP, in Peru where I had been employed during the 1970s) funded by the UK’s Overseas Development Administration (ODA), the forerunner of today’s Department for International Development (DFID).

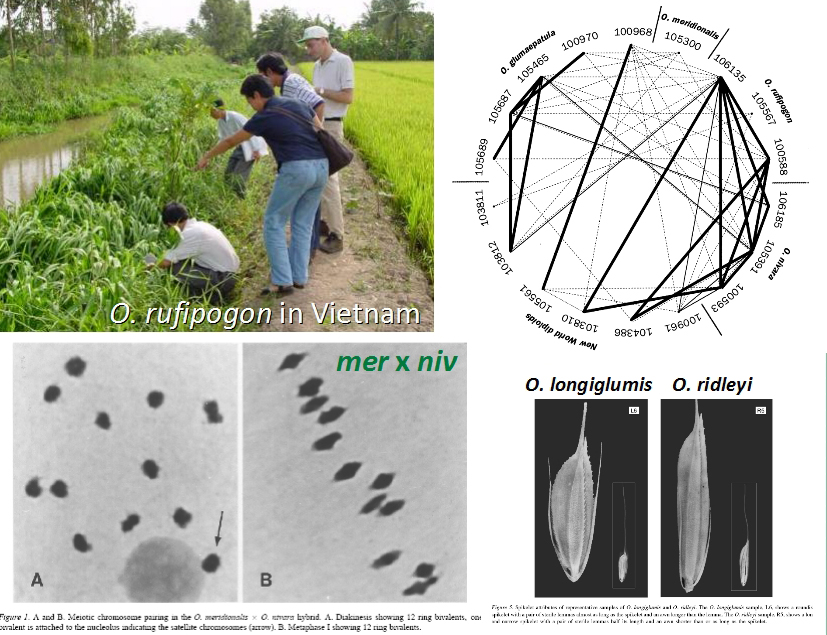

I actually spent 27 years working overseas for two international agricultural research centers in South and Central America, and in the Philippines, from 1973-1981 and from 1991-2010. These were CIP as I just mentioned, and the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI), a globally-important research center in Los Baños, south of Manila in the Philippines, working throughout Asia where rice is the staple food crop, and collaborating with the Africa Rice Centre (WARDA) in Africa, and the International Center for Tropical Agriculture (CIAT) in Latin America.

All four centers are members of the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (or CGIAR) that was established in 1971 to support investments in research and technology development geared toward increasing food production in the food-deficit countries of the world.

All four centers are members of the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (or CGIAR) that was established in 1971 to support investments in research and technology development geared toward increasing food production in the food-deficit countries of the world.

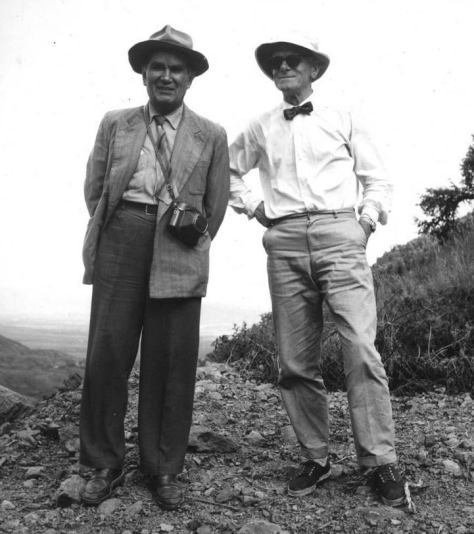

Dr Norman Borlaug

The CGIAR developed from earlier initiatives, going back to the early 1940s when the Rockefeller Foundation supported a program in Mexico prominent for the work of Norman Borlaug (who would be awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1970).

By 1960, Rockefeller was interested in expanding the possibilities of agricultural research and, joining with the Ford Foundation, established IRRI to work on rice in the Philippines, the first of what would become the CGIAR centers. In 2009/2010 IRRI celebrated its 50th anniversary. Then, in 1966, came the maize and wheat center in Mexico, CIMMYT—a logical development from the Mexico-Rockefeller program. CIMMYT was followed by two tropical agriculture centers, IITA in Nigeria and CIAT in Colombia, in 1967. Today, the CGIAR supports a network of 15 research centers around the world.

Peru (CIP); Colombia (CIAT); Mexico (CIMMYT); USA (IFPRI); Ivory Coast (Africa Rice); Nigeria (IITA); Kenya (ICRAF and ILRI); Lebanon (ICARDA); Italy (Bioversity International); India (ICRISAT); Sri Lanka (IWMI); Malaysia (Worldfish); Indonesia (CIFOR); and Philippines (IRRI)

The origins of the CGIAR and its evolution since 1971 are really quite interesting, involving the World Bank as the prime mover.

In 1969, World Bank President Robert McNamara (who had been US Secretary of Defense under Presidents Kennedy and Johnson) wrote to the heads of the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) in Rome and the United Nations Development Fund (UNDP) in New York saying: I am writing to propose that the FAO, the UNDP and the World Bank jointly undertake to organize a long-term program of support for regional agricultural research institutes. I have in mind support not only for some of the existing institutes, including the four now being supported by the Ford and Rockefeller Foundations [IRRI, CIMMYT, IITA, and CIAT], but also, as occasion permits, for a number of new ones.

In 1969, World Bank President Robert McNamara (who had been US Secretary of Defense under Presidents Kennedy and Johnson) wrote to the heads of the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) in Rome and the United Nations Development Fund (UNDP) in New York saying: I am writing to propose that the FAO, the UNDP and the World Bank jointly undertake to organize a long-term program of support for regional agricultural research institutes. I have in mind support not only for some of the existing institutes, including the four now being supported by the Ford and Rockefeller Foundations [IRRI, CIMMYT, IITA, and CIAT], but also, as occasion permits, for a number of new ones.

Just click on this image to the left to open an interesting history of the CGIAR, published a few years ago when it celebrated its 40th anniversary.

Just click on this image to the left to open an interesting history of the CGIAR, published a few years ago when it celebrated its 40th anniversary.

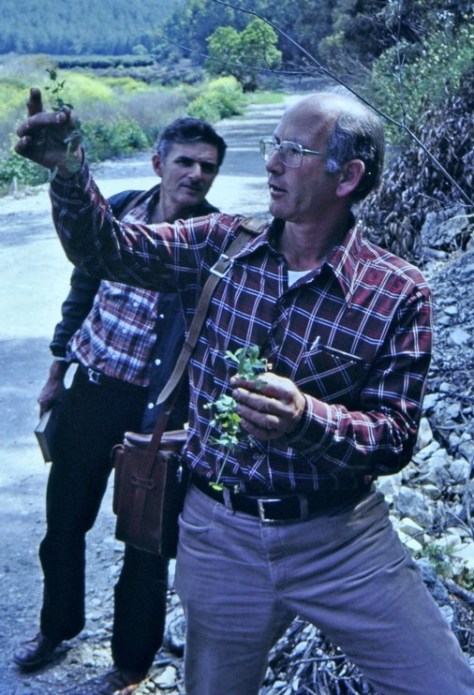

I joined CIP in January 1973 as an Associate Taxonomist, not longer after it became a member of the CGIAR. In fact, my joining CIP had been delayed by more than a year (from September 1971) because the ODA was still evaluating whether to provide funds to CIP bilaterally or join the multilateral CGIAR system (which eventually happened). During 1973 or early 1974 I had the opportunity of meeting McNamara during his visit to CIP, something that had quite an impression on a 24 or 25 year old me.

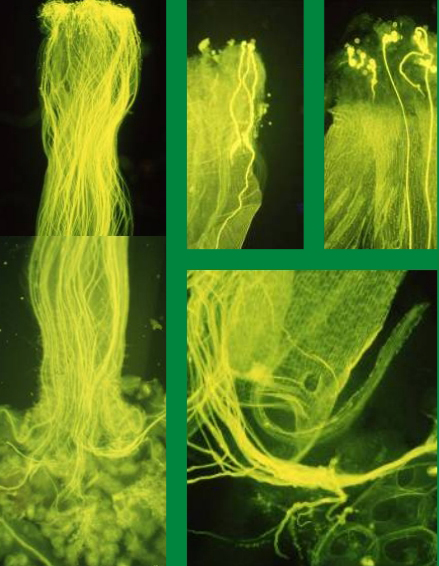

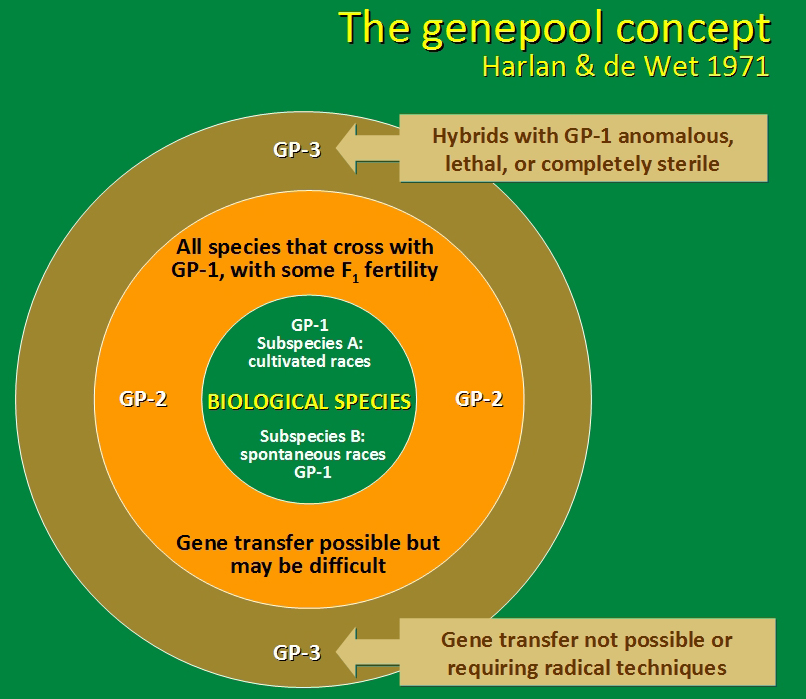

In the first couple of decades the primary focus of the CGIAR was on enhancing the productivity of food crops through plant breeding and the use of genetic diversity held in the large and important genebanks of eleven centers. Towards the end of the 1980s and through the 1990s, the CGIAR centers took on a research role in natural resources management, an approach that has arguably had less success than crop productivity (because of the complexity of managing soil and water systems, ecosystems and the like).

In research approaches pioneered by CIP, a close link between the natural and social sciences has often been a feature of CGIAR research programs. It’s not uncommon to find plant breeders or agronomists, for example working alongside agricultural economists or anthropologists and sociologists, who provide the social context for the research for development that is at the heart of what the CGIAR does.

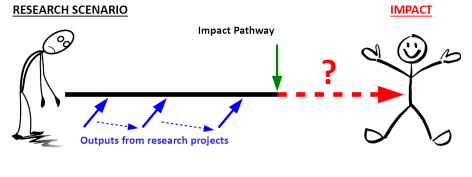

And it’s this research for development—rather than research for its own sake (as you might find in any university department)—that sets CGIAR research apart. I like to visualize it in this way. A problem area is identified that affects the livelihoods of farmers and those who depend on agriculture for their well-being. Solutions are sought through appropriate research, leading (hopefully) to positive outcomes and impacts. And impacts from research investment are what the donor community expects.

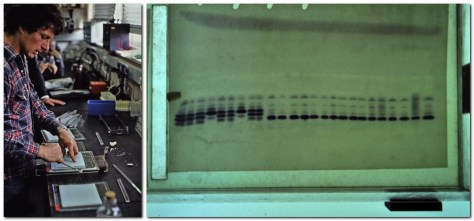

Of course, by its very nature, not all research leads to positive outcomes. If we knew the answers beforehand there would be no need to undertake any research at all. Unlike scientists who pursue knowledge for its own sake (as with many based in universities who develop expertise in specific disciplines), CGIAR scientists are expected to contribute their expertise and experience to research agendas developed by others. Some of this research can be quite basic, as with the study of crop genetics and genomes, for example, but always with a focus on how such knowledge can be used to improve the livelihoods of resource-poor farmers. Much research is applied. But wherever the research sits on the basic to applied continuum, it must be of high quality and stand up to scrutiny by the scientific community through peer-publication. In another blog post, I described the importance of good science at IRRI, for example, aimed at the crop that feeds half the world’s population in a daily basis.

Of course, by its very nature, not all research leads to positive outcomes. If we knew the answers beforehand there would be no need to undertake any research at all. Unlike scientists who pursue knowledge for its own sake (as with many based in universities who develop expertise in specific disciplines), CGIAR scientists are expected to contribute their expertise and experience to research agendas developed by others. Some of this research can be quite basic, as with the study of crop genetics and genomes, for example, but always with a focus on how such knowledge can be used to improve the livelihoods of resource-poor farmers. Much research is applied. But wherever the research sits on the basic to applied continuum, it must be of high quality and stand up to scrutiny by the scientific community through peer-publication. In another blog post, I described the importance of good science at IRRI, for example, aimed at the crop that feeds half the world’s population in a daily basis.

Since 1972 (up to 2016 which was the latest audited financial statement) the CGIAR and its centers have received USD 15.4 billion. To some, that might seem an enormous sum dedicated to agricultural research, even though it was received over a 45 year period. As I pointed out earlier with regard to rice, the CGIAR centers focus on the crops and farming systems (in the broadest sense) in some of the poorest countries of the world, and most of the world’s population.

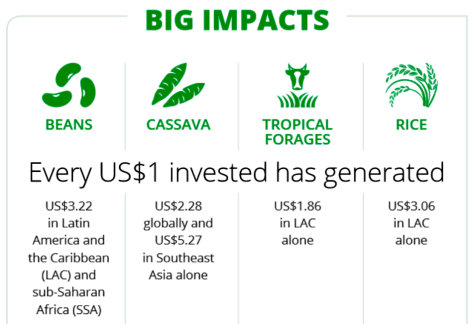

But has that investment achieved anything? Well, there are several ways of measuring impact, the economic return to investment being one. Just look at these impressive figures from CIAT in Colombia that undertakes research on beans, cassava, tropical forages (for pasture improvement), and rice.

For even more analysis of the impact of CGIAR research take a look at the 2010 Food Policy paper by agricultural economists and Renkow and Byerlee.

Over the years, however, the funding environment has become tighter, and donors to the CGIAR have demanded greater accountability. Nevertheless, in 2018 the CGIAR has an annual research portfolio of just over US$900 million with 11,000 staff working in more than 70 countries around the world. CGIAR provides a participatory mechanism for national governments, multilateral funding and development agencies and leading private foundations to finance some of the world’s most innovative agricultural research.

The donors are not a homogeneous group however. They obviously differ in the amounts they are prepared to commit to research for development. They focus on different priority regions and countries, or have interests in different areas of science. Some donors like to be closely involved in the research, attending annual progress meetings or setting up their own monitoring or reviews. Others are much more hands-off.

When I joined the CGIAR in 1973, unrestricted funds were given to centers, we developed our annual work programs and budget, and got on with the work. Moving to Costa Rica in 1976 to lead CIP’s regional program in Mexico, Central America and the Caribbean, I had an annual budget and was expected to send a quarterly report back to HQ in Lima. Everything was done using snail mail or telex. No email demands to attend to on almost a daily basis.

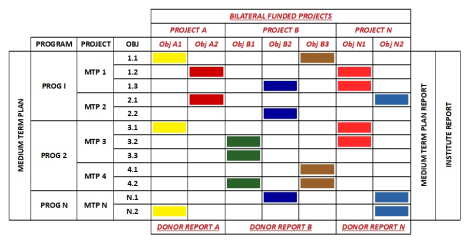

Much of the research carried out in the centers is now funded from bilateral grants from a range of donors. Just look at the number and complexity of grants that IRRI manages (see Exhibit 2 – page 41 and following – from the 2016 audited financial statement). Each of these represents the development of a grant proposal submitted for funding, with its own objectives, impact pathway, expected outputs and outcomes. These then have to be mapped to the CGIAR cross-center programs (in the past these were the individual center Medium Term Plans), in terms of relevance, staff time and resources.

What it also means is that staff spend a considerable amount of time writing reports for the donors: quarterly, biannually, or annually. Not all have the same format, and it’s quite a challenge I have to say, to keep on top of that research complexity. In the early 2000s the donors also demanded increased attention to the management of risk, and I have written about that elsewhere in this blog.

And that’s how I got into research management in 2001, when IRRI Director General Ron Cantrell invited me to join the senior management team as Director for Program Planning & Coordination (later Communications).

And that’s how I got into research management in 2001, when IRRI Director General Ron Cantrell invited me to join the senior management team as Director for Program Planning & Coordination (later Communications).

For various reasons, the institute did not have a good handle on current research grants, nor their value and commitments. There just wasn’t a central database of these grants. Such was the situation that several donors were threatening to withhold future grants if the institute didn’t get its act together, and begin accounting more reliably for the funding received, and complying with the terms and conditions of each grant.

Within a week I’d identified most (but certainly not all) active research grants, even those that had been completed but not necessarily reported back to the donors. It was also necessary to reconcile information about the grants with that held by the finance office who managed the financial side of each grant. Although I met resistance for several months from finance office staff, I eventually prevailed and had them accept a system of grant identification using a unique number. I was amazed that they were unable to understand from the outset how and why a unique identifier for each grant was not only desirable but an absolute necessity. I found that my experience in managing the world’s largest genebank for rice with over 100,000 samples or accessions stood me in good stead in this respect. Genebank accessions have a range of information types that facilitate their management and conservation and use. I just treated research grants like genebank accessions, and built our information systems around that concept.

Eric Clutario

I was expressly fortunate to recruit a very talented database manager, Eric Clutario, who very quickly grasped the concepts behind what I was truing to achieve, and built an important online information management system that became the ‘envy’ of many of the other centers.

We quickly restored IRRI’s trust with the donors, and the whole process of developing grant proposals and accounting for the research by regular reporting became the norm at IRRI. By the time IRRI received its first grant from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation (for work on submergence tolerant rice) all the project management systems had been in place for several years and we coped pretty well with a complex and detailed grant proposal.

Since I retired from IRRI in 2010, and after several years of ‘reform’ the structure and funding of the CGIAR has changed somewhat. Centers no longer prepare their own Medium Term Plans. Instead, they commit to CGIAR Research Programs and Platforms. Some donors still provide support with few restrictions on how and where it can be spent. Most funding is bilateral support however, and with that comes the plethora of reporting—and accountability—that I have described.

Managing a research agenda in one of the CGIAR centers is much more complex than in a university (where each faculty member ‘does their own thing’). Short-term bilateral funding (mostly three years) on fairly narrow topics are now the components of much broader research strategies and programs. Just click on the image on the right to read all about the research organization and focus of the ‘new’ CGIAR. R4D is very important. It has provided solutions to many important challenges facing farmers and resource poor people in the developing world. Overseas development aid has achieved considerable traction through agricultural research and needs carefully protecting.

Managing a research agenda in one of the CGIAR centers is much more complex than in a university (where each faculty member ‘does their own thing’). Short-term bilateral funding (mostly three years) on fairly narrow topics are now the components of much broader research strategies and programs. Just click on the image on the right to read all about the research organization and focus of the ‘new’ CGIAR. R4D is very important. It has provided solutions to many important challenges facing farmers and resource poor people in the developing world. Overseas development aid has achieved considerable traction through agricultural research and needs carefully protecting.

We also had to choose a short research project, mostly carried out during the summer months through the end of August, and written up and presented for examination in September. While the bulk of the work was carried out following the exams, I think all of us had started on some aspects much earlier in the academic year. In my case, for example, I had chosen a topic on lentil evolution by November 1970, and began to assemble a collection of seeds of different varieties. These were planted (under cloches) in the field by the end of March 1971, so that they were flowering by June. I also made chromosome counts on each accession in my spare time from November onwards, on which my very first

We also had to choose a short research project, mostly carried out during the summer months through the end of August, and written up and presented for examination in September. While the bulk of the work was carried out following the exams, I think all of us had started on some aspects much earlier in the academic year. In my case, for example, I had chosen a topic on lentil evolution by November 1970, and began to assemble a collection of seeds of different varieties. These were planted (under cloches) in the field by the end of March 1971, so that they were flowering by June. I also made chromosome counts on each accession in my spare time from November onwards, on which my very first  At the end of the course, all our work, exams and dissertation, was assessed by an external examiner (a system that is commonly used among universities in the UK). The examiner was

At the end of the course, all our work, exams and dissertation, was assessed by an external examiner (a system that is commonly used among universities in the UK). The examiner was

Ayla came to Birmingham with a clear focus on what she wanted to achieve. She saw the MSc course as the first step to completing her PhD, and even arrived in Birmingham with samples of seeds for her research. During the course she completed a dissertation (with Jack Hawkes) on the origin of rye (Secale cereale), and she continued this project for a further two years or so for her PhD. I don’t recall whether she had the MSc conferred or not. In those days, it was not unusual for someone to convert an MSc course into the first year of a doctoral program; I’m pretty sure this is what Ayla did.

Ayla came to Birmingham with a clear focus on what she wanted to achieve. She saw the MSc course as the first step to completing her PhD, and even arrived in Birmingham with samples of seeds for her research. During the course she completed a dissertation (with Jack Hawkes) on the origin of rye (Secale cereale), and she continued this project for a further two years or so for her PhD. I don’t recall whether she had the MSc conferred or not. In those days, it was not unusual for someone to convert an MSc course into the first year of a doctoral program; I’m pretty sure this is what Ayla did.

Folu married shortly before traveling to Birmingham. Her husband had enrolled for a PhD at University College London. He had seen a small poster about the MSc course at Birmingham on a notice board at the University of Ibadan, Nigeria where Folu had completed her BSc in Botany. She applied successfully for financial support from the Mid-Western Nigeria Government to attend the MSc course, and subsequently her PhD studies.

Folu married shortly before traveling to Birmingham. Her husband had enrolled for a PhD at University College London. He had seen a small poster about the MSc course at Birmingham on a notice board at the University of Ibadan, Nigeria where Folu had completed her BSc in Botany. She applied successfully for financial support from the Mid-Western Nigeria Government to attend the MSc course, and subsequently her PhD studies.

genetic resources the training courses she helped deliver, and the research linkages she promoted among various bodies in Nigeria. She has

genetic resources the training courses she helped deliver, and the research linkages she promoted among various bodies in Nigeria. She has

Per Ardua Ad Alta

Per Ardua Ad Alta My first visit to the university was in May or June 1967—to sit an exam. Biology was one of the four subjects (with Geography, English Literature, and General Studies) I was studying for my

My first visit to the university was in May or June 1967—to sit an exam. Biology was one of the four subjects (with Geography, English Literature, and General Studies) I was studying for my

in the Second Year. With my colleague Brian Ford-Lloyd (with whom I’ve published three books on genetic resources) I developed a Third Year module on genetic resources that seems to have been well-received (from some subsequent feedback I’ve received). I also contributed to a plant pathology module for Third Year students. But the bulk of my teaching was to MSc students on the graduate course on Conservation and Utilization of Plant Genetic Resources – the very course I’d attended a decade earlier. My main focus was crop evolution, germplasm collecting, and agricultural systems, among others. And of course there was supervision of

in the Second Year. With my colleague Brian Ford-Lloyd (with whom I’ve published three books on genetic resources) I developed a Third Year module on genetic resources that seems to have been well-received (from some subsequent feedback I’ve received). I also contributed to a plant pathology module for Third Year students. But the bulk of my teaching was to MSc students on the graduate course on Conservation and Utilization of Plant Genetic Resources – the very course I’d attended a decade earlier. My main focus was crop evolution, germplasm collecting, and agricultural systems, among others. And of course there was supervision of

Springer now has its own in-house genetic resources journal, Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution (I’m a member of the editorial board), but there are others such as Plant Genetic Resources – Characterization and Utilization (published by Cambridge University Press). Nowadays there are more journals to choose from dealing with disciplines like seed physiology, molecular systematics and ecology, among others, in which papers on genetic resources can find a home.

Springer now has its own in-house genetic resources journal, Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution (I’m a member of the editorial board), but there are others such as Plant Genetic Resources – Characterization and Utilization (published by Cambridge University Press). Nowadays there are more journals to choose from dealing with disciplines like seed physiology, molecular systematics and ecology, among others, in which papers on genetic resources can find a home.

There’s been quite a bit in the news again recently about the value of a university education, after George Osbourne, the UK’s Chancellor of the Exchequer,

There’s been quite a bit in the news again recently about the value of a university education, after George Osbourne, the UK’s Chancellor of the Exchequer,

What about identical monozygotic twins, such as

What about identical monozygotic twins, such as

But a yellow sweetpea (Lathyrus odoratus)? From images I’ve viewed on the web, many are not true sweetpeas but other species of Lathyrus. It seems, however, that some creamy-yellow varieties have been developed, although a deep yellow one has not yet been produced that I could sniff out. Most are are white, red, pink, blue, or purple, and shades in between, and most of the varieties on the market have large, blousy and delicately fragrant blooms.

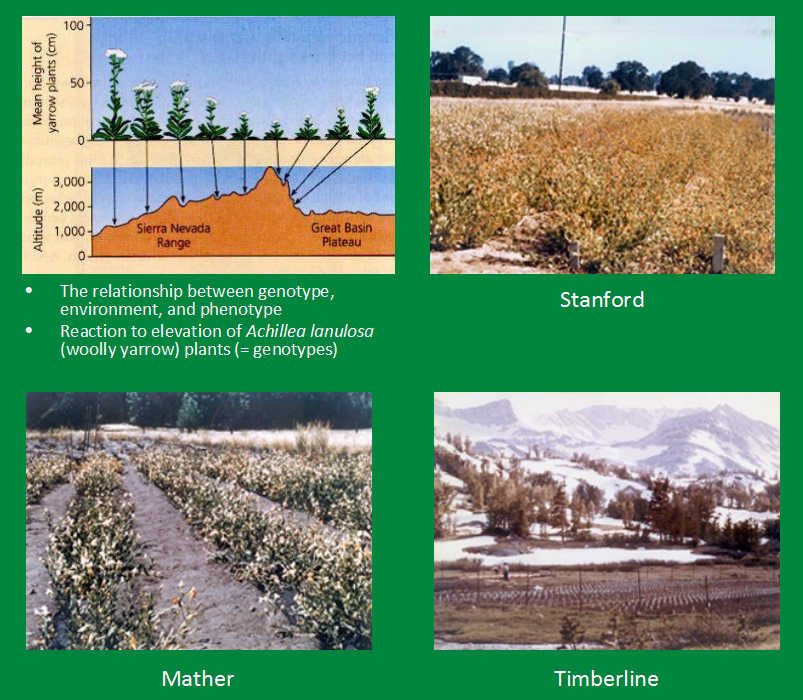

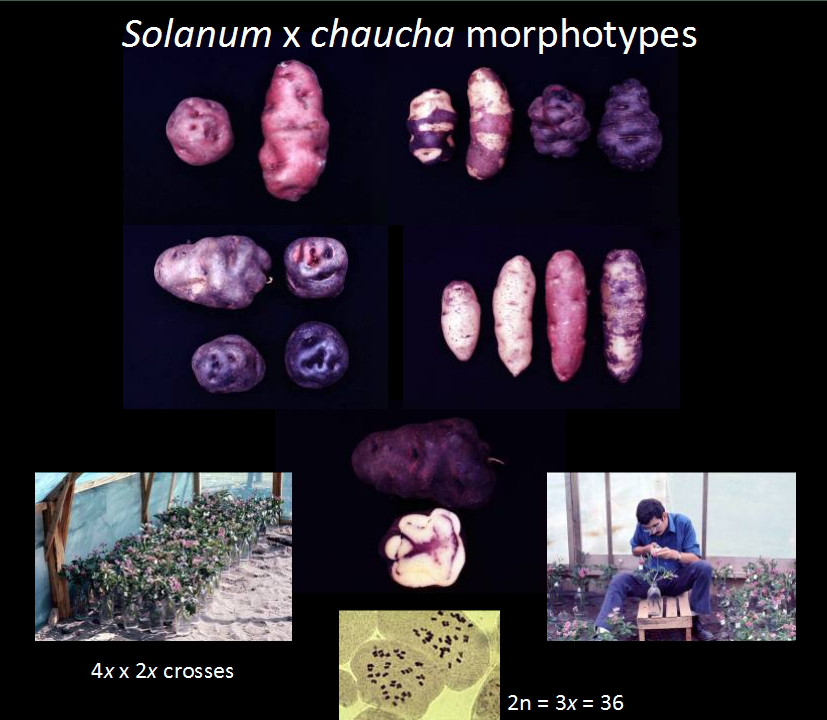

But a yellow sweetpea (Lathyrus odoratus)? From images I’ve viewed on the web, many are not true sweetpeas but other species of Lathyrus. It seems, however, that some creamy-yellow varieties have been developed, although a deep yellow one has not yet been produced that I could sniff out. Most are are white, red, pink, blue, or purple, and shades in between, and most of the varieties on the market have large, blousy and delicately fragrant blooms. Humble? Boiled, mashed, fried, roast, chipped or prepared in many other ways, the potato is surely the King of Vegetables. And for 20 years in the 1970s and 80s, potatoes were the focus of my own research.

Humble? Boiled, mashed, fried, roast, chipped or prepared in many other ways, the potato is surely the King of Vegetables. And for 20 years in the 1970s and 80s, potatoes were the focus of my own research.

In 1989, my former colleagues at the University of Birmingham, Brian Ford-Lloyd and Martin Parry, and I organized a two-day symposium on genetic resources and climate change. The papers presented were published in Climatic Change and Plant Genetic Resources by Belhaven Press (ISBN 1 85293 102 7), edited by me and the other two.

In 1989, my former colleagues at the University of Birmingham, Brian Ford-Lloyd and Martin Parry, and I organized a two-day symposium on genetic resources and climate change. The papers presented were published in Climatic Change and Plant Genetic Resources by Belhaven Press (ISBN 1 85293 102 7), edited by me and the other two. In a particularly prescient chapter, the late Professor Harold Woolhouse discussed how photosynthetic biochemistry is relevant to adaptation to climate change. Two decades later the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) based in the Philippines is leading a worldwide effort to turbocharge the photosynthesis of rice, by converting the plant from so-called C3 to C4 photosynthesis.

In a particularly prescient chapter, the late Professor Harold Woolhouse discussed how photosynthetic biochemistry is relevant to adaptation to climate change. Two decades later the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) based in the Philippines is leading a worldwide effort to turbocharge the photosynthesis of rice, by converting the plant from so-called C3 to C4 photosynthesis.

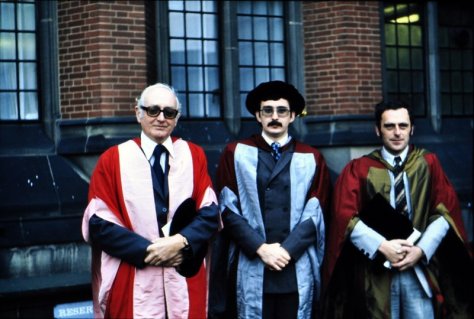

Michael Jackson is the Managing Editor for this book. He retired from the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) in 2010. For 10 years he was Head of the Genetic Resources Center, managing the International Rice Genebank, one of the world’s largest and most important genebanks. For nine years he was Director for Program Planning and Communications. He was Adjunct Professor of Agronomy at the University of the Philippines-Los Baños. During the 1980s he was Lecturer in the School of Biological Sciences at the University of Birmingham, focusing on the conservation and use of plant genetic resources. From 1973-81 he worked at the International Potato Center, in Lima, Perú and in Costa Rica. He now works part-time as an independent agricultural research and planning consultant. He was appointed OBE in The Queen’s New Year’s Honours 2012, for services to international food science.

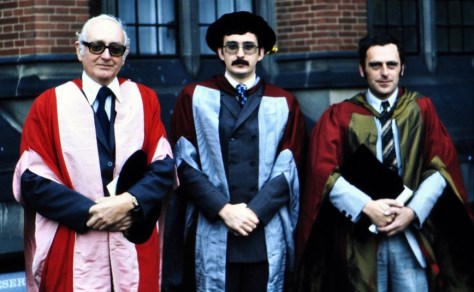

Michael Jackson is the Managing Editor for this book. He retired from the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) in 2010. For 10 years he was Head of the Genetic Resources Center, managing the International Rice Genebank, one of the world’s largest and most important genebanks. For nine years he was Director for Program Planning and Communications. He was Adjunct Professor of Agronomy at the University of the Philippines-Los Baños. During the 1980s he was Lecturer in the School of Biological Sciences at the University of Birmingham, focusing on the conservation and use of plant genetic resources. From 1973-81 he worked at the International Potato Center, in Lima, Perú and in Costa Rica. He now works part-time as an independent agricultural research and planning consultant. He was appointed OBE in The Queen’s New Year’s Honours 2012, for services to international food science. Brian Ford-Lloyd is Professor of Conservation Genetics at the University of Birmingham, Director of the University Graduate School, and Deputy Head of the School of Biosciences. As Director of the University Graduate School he aims to ensure that doctoral researchers throughout the University are provided with the opportunity, training and facilities to undertake internationally valued research that will lead into excellent careers in the UK and overseas. He draws from his experience of having successfully supervised over 40 doctoral researchers from the UK and many other parts of the world in his chosen research area which includes the study of the natural genetic variation in plant populations, and agricultural plant genetic resources and their conservation.

Brian Ford-Lloyd is Professor of Conservation Genetics at the University of Birmingham, Director of the University Graduate School, and Deputy Head of the School of Biosciences. As Director of the University Graduate School he aims to ensure that doctoral researchers throughout the University are provided with the opportunity, training and facilities to undertake internationally valued research that will lead into excellent careers in the UK and overseas. He draws from his experience of having successfully supervised over 40 doctoral researchers from the UK and many other parts of the world in his chosen research area which includes the study of the natural genetic variation in plant populations, and agricultural plant genetic resources and their conservation. Martin Parry

Martin Parry

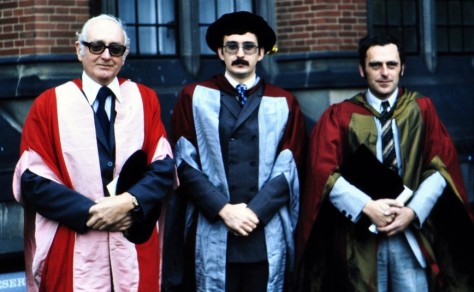

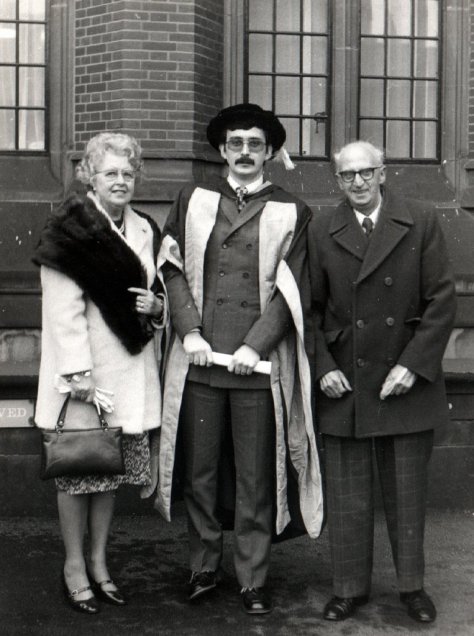

Completing a PhD thesis is one thing. Supervising the research of someone else is another.

Completing a PhD thesis is one thing. Supervising the research of someone else is another. Ardeshir B Damania 1983: Variation in wheat and barley landraces from Nepal and the Yemen Arab Republic

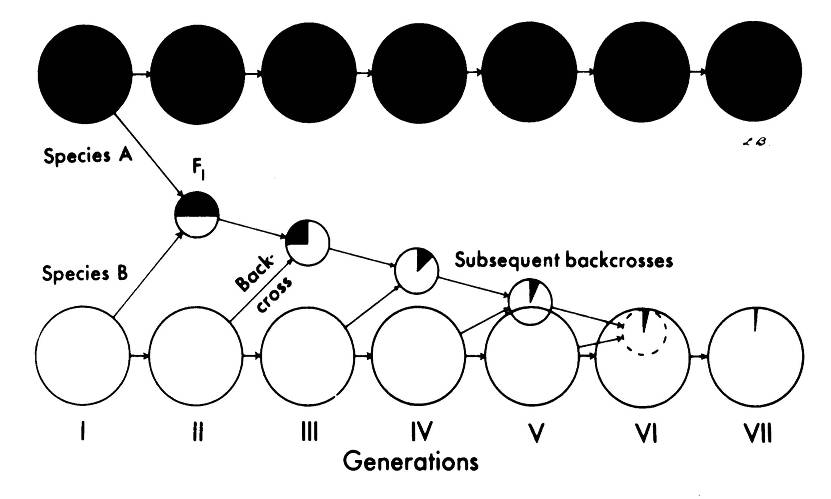

Ardeshir B Damania 1983: Variation in wheat and barley landraces from Nepal and the Yemen Arab Republic Rene Chavez 1984: The use of wide crosses in potato breeding

Rene Chavez 1984: The use of wide crosses in potato breeding Denise B Clugston 1988: Embryo culture and protoplast fusion for the introduction of Mexican wild species germplasm into the cultivated potato

Denise B Clugston 1988: Embryo culture and protoplast fusion for the introduction of Mexican wild species germplasm into the cultivated potato Carlos Arbizu 1990: The use of Solanum acaule as a source of resistance to potato spindle tuber viroid (PSTV) and potato leaf roll virus (PLRV)

Carlos Arbizu 1990: The use of Solanum acaule as a source of resistance to potato spindle tuber viroid (PSTV) and potato leaf roll virus (PLRV) Abdul Ghani Yunus 1990: Biosystematics of Lathyrus Section Lathyrus with special reference to the grass pea, L. sativus L.

Abdul Ghani Yunus 1990: Biosystematics of Lathyrus Section Lathyrus with special reference to the grass pea, L. sativus L. F Javier Franisco Ortega 1992: An ecogeographical study within the Chamaecytisus proliferus (L.fil.) Link complex (Fabaceae: Genisteae) in the Canary Islands

F Javier Franisco Ortega 1992: An ecogeographical study within the Chamaecytisus proliferus (L.fil.) Link complex (Fabaceae: Genisteae) in the Canary Islands Susan A Juned 1994: Somaclonal variation in the potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) cultivar Record with particular reference to the reducing sugar variation after cold storage

Susan A Juned 1994: Somaclonal variation in the potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) cultivar Record with particular reference to the reducing sugar variation after cold storage