For 20 years before I joined the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) in the Philippines in July 1991, as head of the Genetic Resources Center (GRC), my career in international agricultural research at the International Potato Center (CIP, 1973-1981) in Peru and academia (at The University of Birmingham, 1981-1991) focused on potatoes and legume species. Although I remained at IRRI until 2010 (when I retired), I was head of GRC for just a decade, after which I moved to a senior management position.

For 20 years before I joined the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) in the Philippines in July 1991, as head of the Genetic Resources Center (GRC), my career in international agricultural research at the International Potato Center (CIP, 1973-1981) in Peru and academia (at The University of Birmingham, 1981-1991) focused on potatoes and legume species. Although I remained at IRRI until 2010 (when I retired), I was head of GRC for just a decade, after which I moved to a senior management position.

I’d travelled in Asia only twice before. And one of those trips had been to IRRI in January 1991 for interview. The other, in 1985, was to attend a genetic resources conference in Jakarta, Indonesia.

IRRI research center in Los Baños. GRC is housed in the Brady Building on the extreme right. Other buildings have been added since the photo was taken.

So my experience in Asia was limited to say the least, and non-existent for rice. Joining IRRI was certainly a challenge. Why?

In the experiment field at IRRI research center in 2010, with Mt Makiling in the background. I bought that sombrero in Peru in January 1973, just a few days after I arrived there to begin my career in international agricultural research at CIP. The hat is still going strong 50+ years later – not so sure about the wearer.

At IRRI, I had to learn about rice from scratch, manage one of the world’s most important genebanks (I’d never managed a genebank before), and supervise a group of more than 70 professional and support staff. Furthermore, I had to learn (quickly) to empathise with a very different culture, specifically Filipino but Asian more broadly (very different from that I’d experienced in Latin America). It wasn’t so straightforward, but I was up for the challenge.

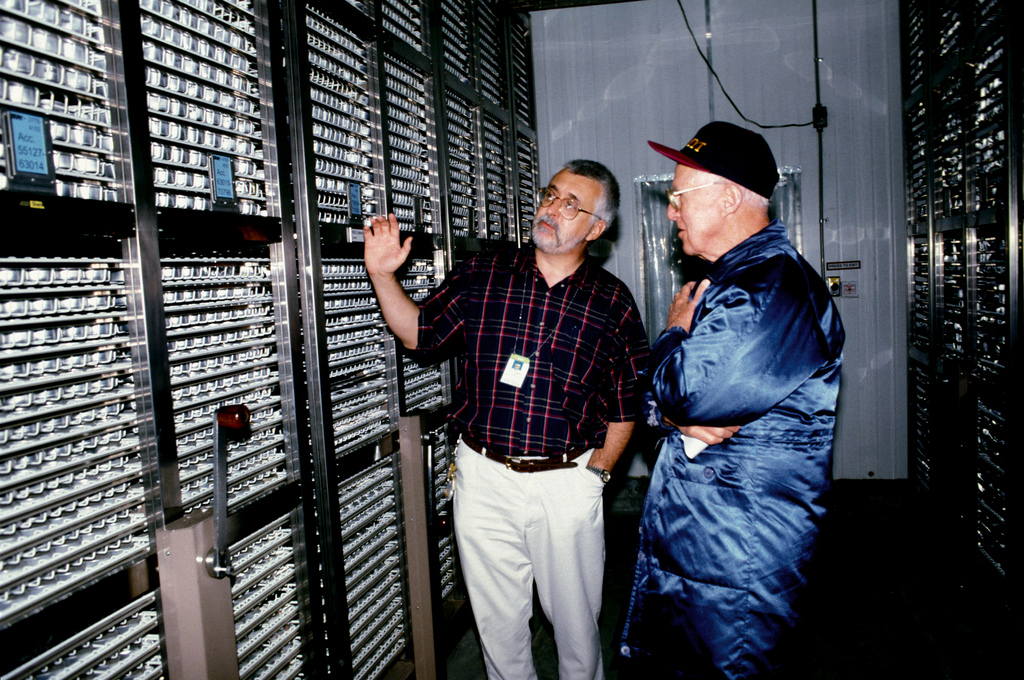

In 1991, Klaus Lampe (right, who passed away earlier this year) was IRRI’s Director General, who was appointed in 1988 to revive the institute’s status in the world of international agricultural research. That meant not only refurbishment of IRRI’s laboratories and offices at its Los Baños campus headquarters, but also involved a significant turnover of staff, replacing many (who had been with IRRI for a decade or more, even since the 1960s) with a cohort of younger staff who could bring new ideas, enthusiasm, and skills to IRRI’s research for development agenda. I was part of that recruitment cohort.

I first heard about the GRC position at IRRI in September 1990. It was advertised as a new department, bringing together the rice genebank (then known as the International Rice Germplasm Center, later renamed the International Rice Genebank) and INGER, a global network for testing rice varieties and breeding lines. While the head would have overall management responsibility for GRC, his/her day-to-day duties would focus on the genebank, while another staff member was the INGER leader.

During my interviews at IRRI over three days I indicated I would only be interested in the position if there was a specific research component and funding to support it, something that had not been envisaged when GRC was established and the position advertised.

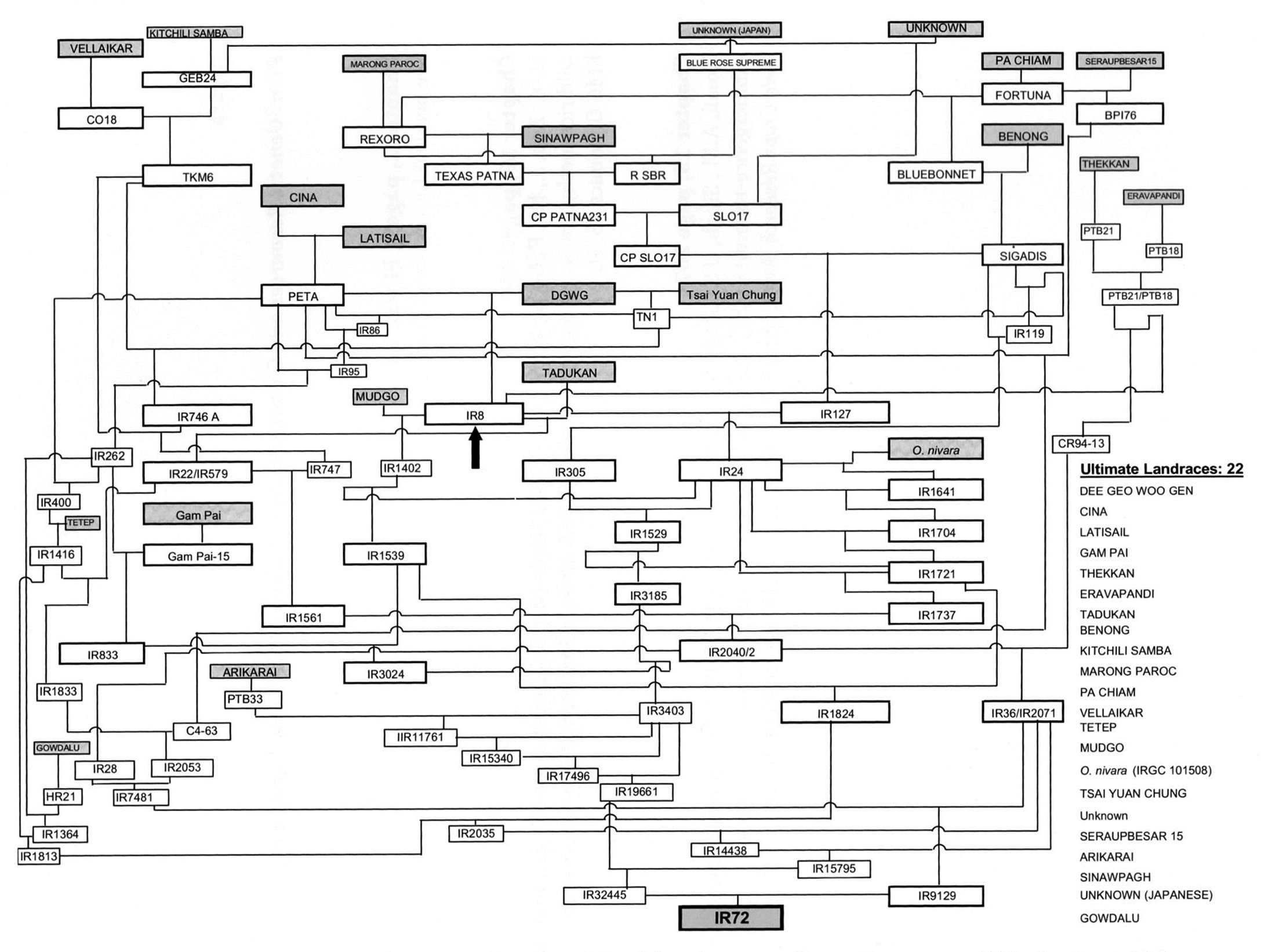

I must have been persuasive because I was offered the position, and Lampe approved a research role for GRC. Specifically for research aimed at managing and using the important rice germplasm collection of indigenous varieties, improved lines, genetic stocks, and wild species that, in 1991, totalled around 75,000 seed samples or accessions.

But in July 1991, research per se was not an immediate priority. There were other, more pressing issues to be attended to first—and their outcome equally as important as our many research publications.

But in July 1991, research per se was not an immediate priority. There were other, more pressing issues to be attended to first—and their outcome equally as important as our many research publications.

I had to quickly familiarise myself with IRRI’s research and management culture as one of the world’s leading agricultural research centers (and oldest among the research centers supported through the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research, or CGIAR), build a GRC culture and, specifically, work out just how the genebank could be better managed and the roles of each of the staff.

My predecessor (as head of the International Rice Germplasm Center) was eminent rice geneticist and upland rice breeder, Dr TT Chang. ‘TT’, as he was known, ran the genebank (I quickly discovered) along the lines: ‘Do as I say’, and staff had little or no individual responsibility or leeway to manage their work more effectively.

It didn’t take me long to realise that changes could and should be made to increase efficiency, and eliminate duplication of effort among staff. I needed to assign specific responsibilities (and accountability) to each staff member for seed conservation, germplasm multiplication and rejuvenation, for data management, among others, and also identify individuals who might take on a specific research role.

After six months of asking lots of questions and discussing the genebank operations, I had a genebank strategy and plan ready. And because my staff had been involved in developing the plan, its implementation was fairly plain-sailing from then on.

I’m not going to detail here the sorts of changes that were made. Almost none of the genebank operations in the field or in storage escaped our attention. Job descriptions were rewritten, and positions upgraded to reflect new responsibilities.

Inside the International Rice Genebank, with Pola de Guzman who became the genebank manager.

The genebank was fortunate to be included in the institute’s refurbishment plan, so we upgraded many of its facilities and installed a dedicated seed drying room, a significant addition.

In this post I summarised what it entails to run a genebank for rice. And check out this video I made about the genebank in 2015 on a return visit to IRRI. Many of the staff who feature in the video have themselves now retired and some have sadly died.

Among the tasks we undertook was revision of the data management system, one of the most important components of genebank operations. For a number of reasons the data system I inherited was not really fit for purpose. It took two years to complete all the changes!

And for the sake of my successor(s), we wrote a genebank operations manual, the first of its kind among the CGIAR genebanks. Publishing the manual was not the only ‘first’ that IRRI achieved.

The fruits of our endeavours were recognised around 1994 when the CGIAR launched an external review of the center genebanks. The reviewers concluded that IRRI’s genebank was ‘a model for others to emulate‘. Our hard work had paid off. But we weren’t complacent, striving to make more improvements which were taken further by my immediate successor, Dr Ruaraidh Sackville Hamilton.

The management and status of the International Rice Genebank

Over the decade I was in charge of IRRI’s genebank, we published several papers and book chapters describing the rice collection and its management (and in the wider CGIAR context), how much it cost to run, who had requested germplasm and for what purpose, using biotechnology for conservation, as well as issues related to the management of intellectual property.

During the mid-1990s, and post-Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) there was concern internationally about how germplasm was being conserved in the 11 CGIAR center genebanks.

The CGIAR’s System-wide Genetic Resources Program (SGRP, launched in 1994 and which I chaired for several years, seen in the image below meeting in Rome had members from all CGIAR centers) responded to these concerns by publishing Biodiversity in Trust in 1997.

The CGIAR’s System-wide Genetic Resources Program (SGRP, launched in 1994 and which I chaired for several years, seen in the image below meeting in Rome had members from all CGIAR centers) responded to these concerns by publishing Biodiversity in Trust in 1997.

The chapters described the status and management of each of the crops held in trust in the genebanks. The rice chapter had authors from IRRI, Africa Rice (in Ivory Coast), IITA (in Nigeria), and CIAT (in Colombia), all of which had rice collections, with that at IRRI the largest and most comprehensive.

In the 1990s, there was considerable interest in developing ‘core collections’ (first proposed by genetic resources pioneer, Sir Otto Frankel (right, one of the pioneers of the plant genetic resources conservation movement launched in the 1960s, who I had the pleasure of meeting at that 1985 conference in Jakarta), a subset of the whole collection that encompassed all the diversity—a concept that has been (mis)interpreted in a multiplicity of ways ever since. I’ve never been much of an advocate for core collections, simply because we had so much to achieve to ensure the safety of the whole collection rather concentrate our efforts on a subset. Nevertheless, my colleague Duncan Vaughan (who left IRRI in 1993 to join a research institute in Tsukuba, Japan) and I speculated how a core collection for rice might be assembled.

We published an update in 1999, after we’d had several years of molecular analysis experience.

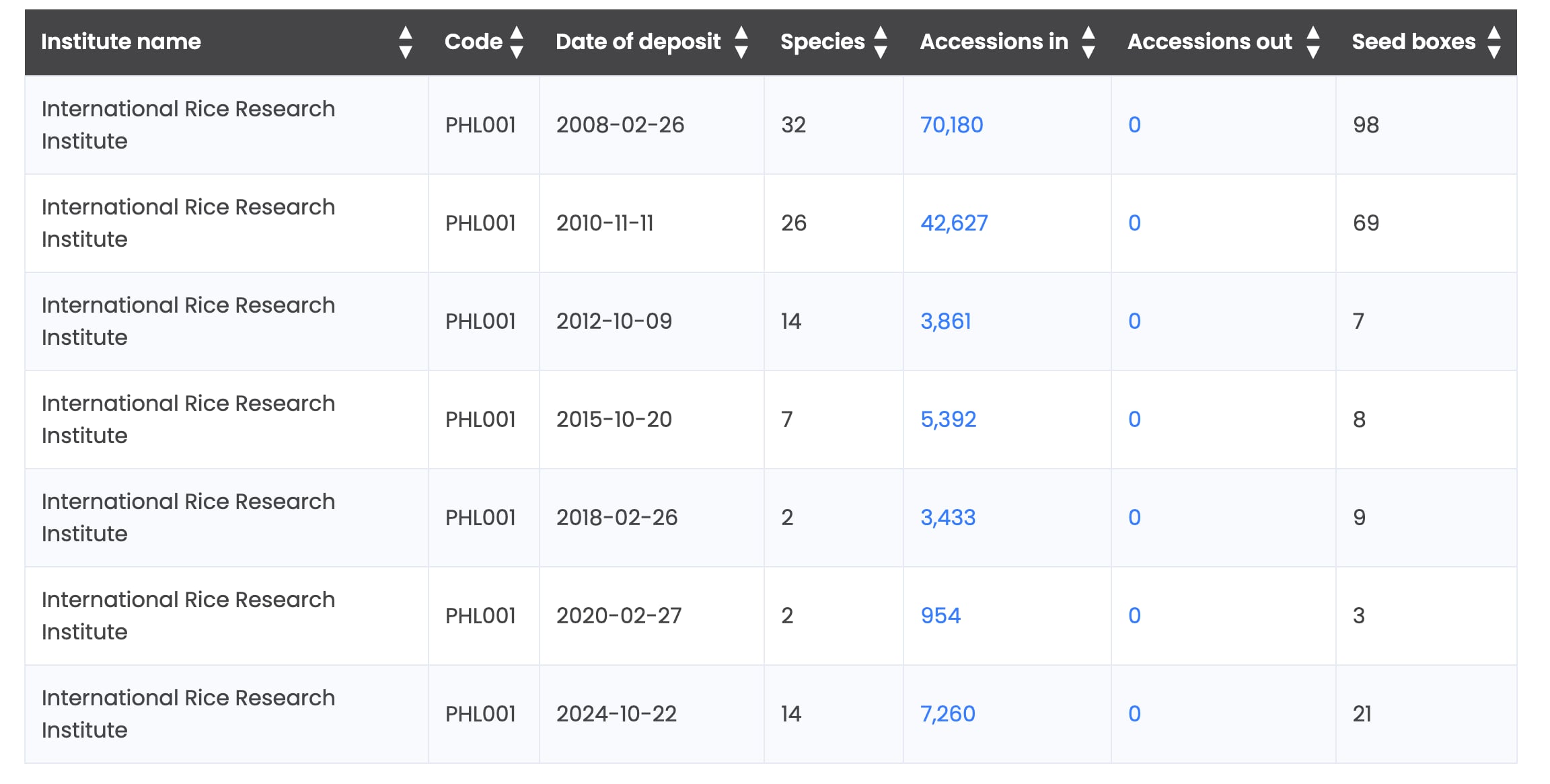

The IRRI collection has been widely used in plant breeding, and rice research in general. It’s not a museum collection, and access to the germplasm is one justification for its continued financial support.

The long-term security of any genebank collection is dependent upon reliability of long-term funding. Fortunately the Crop Trust now provides a significant level of security to genebanks in perpetuity through its Endowment Fund.

But what does it cost to run a genebank like IRRI’s? In the late 1990s, we didn’t really have a good handle on this. With the help of agricultural economists Bonwoo Koo, Philip Pardey, and Brian Wright, several of the CGIAR genebanks made a stab at a costing exercise – subsequently revised since methodologies have been improved. Here is the original IRRI costing study, published in 2004.

During our research on the breeding relationships of wild and cultivated rices, we used in vitro culture of embryos (on nutrient medium), and over the years adopted various molecular approaches (see below) to study the diversity of the rice collection. Some of these also had implications for intellectual property management, and I addressed some of these issues in this chapter in 1999.

In a later section of this post I describe in more detail how we (with colleagues in the UK) adopted and developed molecular approaches to manage the collection (and study diversity). But here are two general descriptions of what we did.

Post-CBD, and with the coming into force of the International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture, I (together with an FAO consultant Robert Lettington) was asked to provide FAO with an analysis of some of the current developments affecting access to germplasm, including the effects of the development of access legislation under the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), legislation on intellectual property rights (IPRs), and other relevant national legislation.

Now let me turn to GRC research per se, which focused on two main areas:

- managing the germplasm collection; and

- understanding the diversity of rice accessions in the collection.

From the outset it was clear to me that we would need external collaborators simply because we did not have the resources (human, laboratory, or financial) to carry out everything by ourselves. And in the account below, I’ll explain how and with whom we developed such collaboration.

Germplasm conservation

The top priority (or should be) for any genebank manager is to ensure that conserved germplasm is safe and will retain its viability for decades.

Since the IRRI collection comprised rice varieties and wild species from across the world, I was concerned that we had insufficient information how to improve the multiplication of diverse seed samples in one location, namely Los Baños (14°N). While there was quite a body of literature about seed multiplication, drying, and storage from a range of other species, not so much was known then about rice.

So I turned to my good friend at the University of Reading, Professor Richard Ellis (right), a leading expert in seed conservation, and together we successfully applied for one of the UK Overseas Development Administration’s (ODA, later to become the Department for International Development or DfID) ‘Holdback’ grants. This was a scheme in which the ODA set aside a small portion of its overseas aid budget to the CGIAR centers to fund collaborative work between British institutions and centers, but with the bulk of the funds spent in the UK.

Our project focused on how the seed production environment and time of harvest affected seed longevity in storage, leading to a couple of publications that guided our practices in the genebank.

The next step was to expand the research in Los Baños itself looking at more rice varieties in a real rice-growing environment.

The next step was to expand the research in Los Baños itself looking at more rice varieties in a real rice-growing environment.

I recruited Dr N Kameswara Rao (right) from India (who had completed his PhD at Reading) to join GRC on a postdoctoral position for three years.

Kameswara Rao and I published these four papers:

As a result of this project, we made several important changes to germplasm multiplication and rejuvenation, and post-harvest drying and management was enhanced, as I mentioned earlier, with the addition of a dedicated seed drying room (with a capacity of at least 2 tonnes, that allowed seeds to dry slowly) to the genebank.

Seed germination of wild rice species had always been somewhat hit-and-miss, so my staff set up a series of experiments to improve the germination rate, leading to the adoption of different protocols.

Molecular markers – collaboration with the University of Birmingham and the John Innes Centre

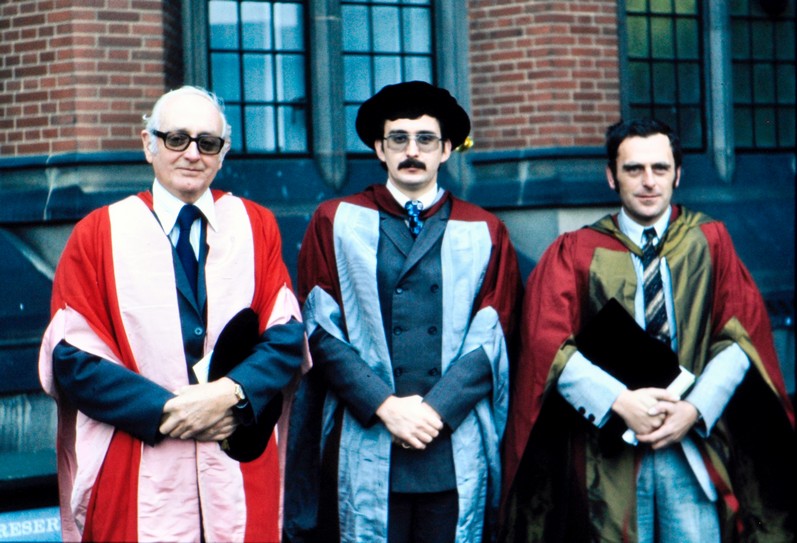

Even before I left the university to join IRRI, I had discussed with my colleagues Brian Ford-Lloyd and John Newbury [1] how we might continue to collaborate. Then, like I had with Richard Ellis at Reading, we successfully applied for a UK ‘Holdback’ grant (R5059) jointly with John Innes Centre (JIC, with the late Professor Mike Gale, FRS) in Norwich, to study how molecular markers could be used to reveal the nature of diversity in the germplasm collection and help in its management. Parminder Virk [2], a quantitative geneticist, joined the project in Birmingham, and added his considerable statistical analysis skills to the research. Dr Glenn Bryan [3] was the lead scientist at JIC.

But not without a little controversy at IRRI. Why should that have been? Well, some of my IRRI colleagues argued that the funds should come directly to the institute since there was a laboratory already established to use molecular markers (mainly Restriction Fragment Length Polymorphism markers or RFLPs), even though that lab was operating at almost full capacity.

They just couldn’t accept that ‘Holdback Funds’ would never be awarded directly to a center, even though we could allocate some of our expenses in the research to the project. In any case, it was clear to me that we had neither the capacity in house, nor did we have the trained personnel in GRC. With that in mind, I was able eventually to send one of my staff, Amita ‘Amy’ Juliano (who sadly passed away around 2004) for several weeks training (on a travel grant from the British Council) in the Birmingham lab, and on her return she set up her own lab in GRC.

L-R: John Newbury, Faye Hughes (lab technician), Parminder Virk (postdoc), visitor, Amy Juliano (IRRI), visitor, me, Brian Ford-Lloyd in the lab at Birmingham.

Birmingham had responsibility for the molecular screening (and development of techniques and methodologies), using PCR-based markers like Random Amplification of Polymorphic DNA or RAPD markers. What we at IRRI contributed was expertise to phenotype rice varieties in the field.

Compared to what molecular markers are available for research today (and more than a decade before the rice genome was sequenced in 2002), and the developments in genome sequencing that have taken place, our initial focus on RAPD markers was just the beginning of an innovative (pioneering even) molecular study of any germplasm collection. And has led to some molecular firsts.

We showed that RAPD markers were useful for expanding our knowledge of diversity beyond the purely morphological or isozyme data then available.

In a particularly significant development we demonstrated how RAPD markers could be used to predict the behaviour of rice varieties in the field (combining excellent molecular analysis with accurate phenotyping). This was one of the first (if not the first) examples of what came to be known as ‘association genetics’, dismissed at the time by many (including Mike Gale) but now widely verified in other species.

Our colleagues at the JIC also developed work on Amplified Fragment Length Polymorphism or AFLP markers to study rice germplasm. A young Chinese scientist, Zhu Jiahui, joined the project and eventually was awarded his PhD for the research.

A couple of PhD students at Birmingham used molecular markers to study material from the collection.

After several years of study we developed a deep appreciation of how molecular markers really did open a window on the diversity of the germplasm collection.

Biosystematics and pre-breeding

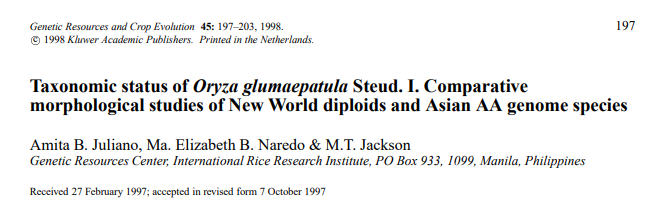

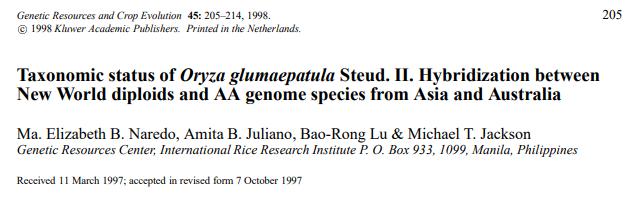

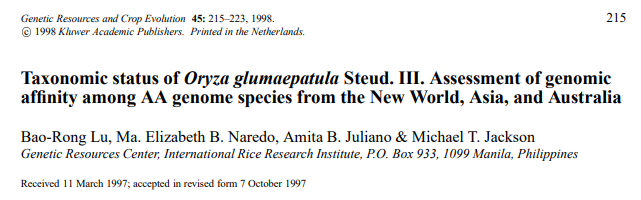

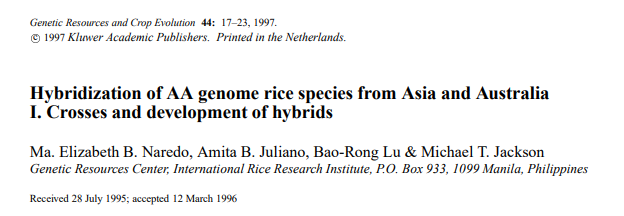

Wild species have been used to improve rice varieties, and the genebank collection holds many accessions of the 20 or so wild Oryza species. However, there had been little systematic study in terms of their taxonomy or their breeding relationships with the cultivated species. We decided to rectify that situation and launched a program to study the variation in and relationships of the wild and cultivated rices, Oryza sativa and Oryza glaberrima.

In 1994 we recruited Chinese cytogeneticist Dr Lu Bao-Rong (right, now at Fudan University in Shanghai) to lead this biosystematics initiative and to continue the collecting of wild species of his predecessor, Dr Duncan Vaughan. The two Filipino support staff were Amy Juliano and Maria Elizabeth ‘Yvette’ Naredo.

Under our supervision, Amy and Yvette carried out some important work on the AA genome rices (the two cultivated species and their closest wild relatives), establishing crossing and embryo rescue protocols.

In all, the biosystematics research led to these papers:

Yvette completed her MS degree at the University of the Philippines-Los Baños, co-supervised by me and a faculty member from the university, for a study on two distantly related species, Oryza ridleyi and Oryza longiglumis. Some years later she went on to complete her PhD as well.

Yvette completed her MS degree at the University of the Philippines-Los Baños, co-supervised by me and a faculty member from the university, for a study on two distantly related species, Oryza ridleyi and Oryza longiglumis. Some years later she went on to complete her PhD as well.

In 1994, I applied to the Swiss government for funding to:

- ‘complete’ the collection of rice varieties (and some wild species) throughout Asia, and wild rices in several African countries, and Costa Rica and Brazil in South America;

- train personnel in national programs the principles and practices of rice germplasm conservation and use (including data management); and

- evaluate the role for on-farm management of rice varieties as a component of genetic conservation.

We received a grant of USD3.286 million, and the project ran until 2000. I’ve written extensively about the project in this blog post. There you will find links to original project reports – and lots more.

Collecting rice germplasm

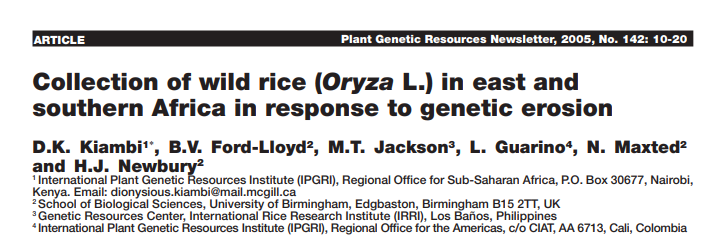

But in terms of collecting, one of my former MSc students at the University of Birmingham, Dr Dan Kiambi (a Kenyan national) coordinated collecting efforts in Africa.

In Asia, few collections of rice germplasm had been made in Laos, due to the conflict that had blighted that country over many years. In fact it’s overall capacity for agricultural R&D was quite limited. At the end of the 1980s, and supported with Swiss funding, IRRI opened a country program office in Vientiane (the capital city), headed by the late Dr John Schiller (right), an Australian agronomist who became a good friend.

In Asia, few collections of rice germplasm had been made in Laos, due to the conflict that had blighted that country over many years. In fact it’s overall capacity for agricultural R&D was quite limited. At the end of the 1980s, and supported with Swiss funding, IRRI opened a country program office in Vientiane (the capital city), headed by the late Dr John Schiller (right), an Australian agronomist who became a good friend.

With funding from the rice biodiversity project, I hired a project scientist based in Vientiane who would work with the Lao national program to collect rice varieties throughout the country (as well as assisting collecting elsewhere if time permitted).

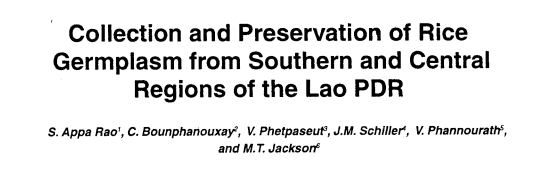

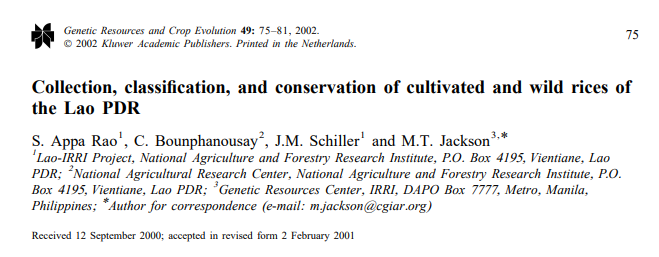

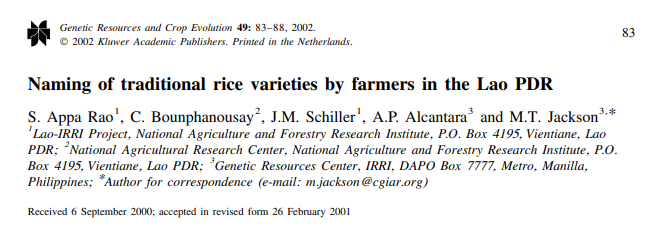

Dr Seepana Appa Rao (right, a germplasm scientist) came to us from a sister center, ICRISAT, in Hyderabad, India and he spent five years in Laos, assembling a comprehensive collection of 13,000 Lao rice samples which were duplicated in the International Rice Genebank. I wrote about this special aspect of the rice biodiversity project here.

Dr Seepana Appa Rao (right, a germplasm scientist) came to us from a sister center, ICRISAT, in Hyderabad, India and he spent five years in Laos, assembling a comprehensive collection of 13,000 Lao rice samples which were duplicated in the International Rice Genebank. I wrote about this special aspect of the rice biodiversity project here.

Appa was an enthusiastic writer and here are two papers about the collections he made.

But Appa didn’t just collect rice varieties and leave it at that. With his Lao colleagues he studied the germplasm, leading to several interesting papers and book chapters.

The following chapters were all published in the same book.

On-farm management of rice genetic resources

During the 1990s there was a concerted effort among some activist NGOs and the like to downplay the important (and safe) role of ex situ conservation in genebanks, instead promoting an in situ on-farm management (conservation) approach that should be adopted. Whereas there was a considerable body of scientific literature to support the efficacy of ex situ conservation, on-farm management seemed to almost be an ideology with little scientific basis to support its long-term consequences in terms of genetic conservation.

I felt we needed to tackle this situation head on, so I hired a population geneticist, Dr Jean-Louis Pham (on secondment from IRD in France) and a Mexican human ecologist, Dr Mauricio Bellon who together would look into the genetic and societal implications of on-farm management. After Mauricio moved to another institute after a couple of years, we recruited Dr Steve Morin, a social anthropologist from Nebraska.

L-R: Jean-Louis Pham, Mauricio Bellon, and Steve Morin

All in all, quite a productive decade, upgrading the genebank and its collection, and establishing excellent collaborations with scientists in the UK and elsewhere, without whom we could never have achieved so much.

My Filipino staff grew in their roles, and the genebank went from strength to strength. I retired just as IRRI reached its Golden Jubilee.

My Filipino staff grew in their roles, and the genebank went from strength to strength. I retired just as IRRI reached its Golden Jubilee.

Although I moved into a program management role after leaving GRC, I retained a keen interest in what my former colleagues were undertaking. And to this day, they keep me posted from time-to-time.

Besides the papers and chapters that I have included above, we presented these papers and posters at conferences. No digital copies are available.

1993

Cabanilla, V.R., M.T. Jackson & T.R. Hargrove, 1993. Tracing the ancestry of rice varieties. Poster presented at the 17th International Congress of Genetics, Birmingham, U.K., August 15-21, 1993. Volume of abstracts, 112-113.

Hunt, E.D., M.T. Jackson, M. Oliva & A. Alcantara, 1993. Employing geographical information systems (GIS) for conserving and using rice germplasm. Poster presented at the 17th International Congress of Genetics, Birmingham, U.K., August 15-21, 1993. Volume of abstracts, 117.

Jackson, M.T., 1993. Biotechnology and the conservation and use of plant genetic resources. Invited paper presented at the Workshop on Biotechnology in Developing Countries, held at the 17th International Congress of Genetics, Birmingham, U.K., August 15-21, 1993.

Jackson, M.T., G.C. Loresto & A.P. Alcantara, 1993. The International Rice Germplasm Center at IRRI. In: The Egyptian Society of Plant Breeding (1993). Crop Genetic Resources in Egypt: Present Status and Future Prospects. Papers of an ESPB Workshop, Giza, Egypt, March 2-3, 1992.

Newbury, H.J., P. Virk, M.T. Jackson, G. Bryan, M. Gale & B.V. Ford-Lloyd, 1993. Molecular markers and the analysis of diversity in rice. Poster presented at the 17th International Congress of Genetics, Birmingham, U.K., August 15-21, 1993. Volume of abstracts, 121-122.

1994

Jackson, M.T., 1994. Care for and use of biodiversity in rice. Invited paper presented at the Symposium on Food Security in Asia, held at the Royal Society, London, November 1, 1994.

Parsons, B.J., B.V. Ford-Lloyd, H.J. Newbury & M.T. Jackson, 1994. Use of PCR-based markers to assess genetic diversity in rice landraces from Bhutan and Bangladesh. Poster presented at the Annual Meeting of the British Ecological Society, held at The University of Birmingham, December 1994.

Virk, P., B.V. Ford-Lloyd, M.T. Jackson & H.J. Newbury, 1994. The use of RAPD analysis for assessing diversity within rice germplasm. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the British Ecological Society, held at The University of Birmingham, December 1994.

1995

Dao The Tuan, Nguyen Dang Khoi, Luu Ngoc Trinh, Nguyen Phung Ha, Nguyen Vu Trong, D.A. Vaughan & M.T. Jackson, 1995. INSA-IRRI collaboration on wild rice collection in Vietnam. In: G.L. Denning & Vo-Tong Xuan (eds.), Vietnam and IRRI: A partnership in rice research. International Rice Research Institute, Los Baños, Philippines, and Ministry of Agriculture and Food Industry, Hanoi, Vietnam, pp. 85-88.

Jackson, M.T., 1995. The international crop germplasm collections: seeds in the bank! Invited paper presented at the meeting Economic and Policy Research for Genetic Resources Conservation and Use: a Technical Consultation, held at IFPRI, Washington, D.C., June 21-22, 1995

Jackson, M.T., A. Alcantara, E. Guevarra, M. Oliva, M. van den Berg, S. Erguiza, R. Gallego & M. Estor, 1995. Documentation and data management for rice genetic resources at IRRI. Paper presented at the Planning Meeting for the System-wide Information Network for Genetic Resources (SINGER), held at CIMMYT, Mexico, October 2-6, 1995.

Jackson, M.T., B.R. Lu, G.C. Loresto & F. de Guzman, 1995. The conservation of rice genetic resources at the International Rice Research Institute. Paper presented at the International Symposium on Research and Utilization of Crop Germplasm Resources held in Beijing, People’s Republic of China, June 1-3, 1995.

Kameswara Rao, N. & M.T. Jackson, 1995. Seed production strategies for conservation of rice genetic resources. Poster presented at the Fifth International Workshop on Seeds, University of Reading, September 11-15, 1995.

Lu, B.R., A. Juliano, E. Naredo & M.T. Jackson, 1995. The conservation and study of wild Oryza species at the International Rice Research Institute. Paper presented at the International Symposium on Research and Utilization of Crop Germplasm Resources held in Beijing, People’s Republic of China, June 1-3, 1995.

Pham, J.L., M.R. Bellon & M.T. Jackson, 1995. A research program on on-farm conservation of rice genetic resources. Poster presented at the Third International Rice Genetics Symposium, Manila, Philippines, October 16-20, 1995.

Reaño, R., M.T. Jackson, F. de Guzman, S. Almazan & G.C. Loresto, 1995. The multiplication and regeneration of rice germplasm at the International Rice Genebank, IRRI. Paper presented at the Discussion Meeting on Regeneration Standards, held at ICRISAT, Hyderabad, India, December 4-7, 1995, sponsored by IPGRI, ICRISAT and FAO.

1996

Appa Rao, S., C. Bounphanousay, V. Phetpaseuth, K. Kanyavong, B. Sengthong, J. M. Schiller, V. Phannourath & M.T. Jackson, 1996. Collection and classification of rice germplasm from the Lao PDR. Part 1. Southern and Central Regions – 1995. Internal report of the National Agricultural Research Center, Dept. of Agriculture and Extension, Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry, Vientiane, Lao PDR, and Genetic Resources Center, International Rice Research Institute (IRRI), Los Baños, Philippines.

Jackson, M.T. & G.C. Loresto, 1996. The role of the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) in supporting national and regional programs. Invited paper presented at the Asia-Pacific Consultation Meeting on Plant Genetic Resources, held in New Delhi, India, November 27-29, 1996.

Jackson, M.T. & R.D. Huggan, 1996. Pflanzenvielfalt als Grundlage der Welternährung. Bulletin—das magazin der Schweizerische Kreditanstalt SKA. March/April 1996, 9-10.

Jackson, M.T., 1996. Intellectual property rights—the approach of the International Rice Research Institute. Invited paper presented at the Satellite Symposium on Biotechnology and Biodiversity: Scientific and Ethical Issues, held in New Delhi, India, November 15-16, 1996.

Jackson, M.T., G.C. Loresto & F. de Guzman, 1996. Partnership for genetic conservation and use: the International Rice Genebank at the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI). Poster presented at the Beltsville Symposium XXI on Global Genetic Resources—Access, Ownership, and Intellectual Property Rights, held in Beltsville, Maryland, May 19-22, 1996.

Virk, P.S., H.J. Newbury, Y. Shen, M.T. Jackson & B.V. Ford-Lloyd, 1996. Prediction of agronomic traits in diverse germplasm of rice and beet using molecular markers. Paper presented at the Fourth International Plant Genome Conference, held in San Diego, California, January 14-18, 1996.

1997

Appa Rao, S., C. Bounphanousay, K. Kanyavong, V. Phetpaseuth, B. Sengthong, J.M. Schiller, S. Thirasack & M.T. Jackson, 1997. Collection and classification of rice germplasm from the Lao PDR. Part 2. Northern, Southern and Central Regions. Internal report of the National Agricultural Research Center, Department of Agriculture and Extension, Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry, Vientiane, Lao PDR, and Genetic Resources Center, International Rice Research Institute (IRRI), Los Baños, Philippines.

1998

Appa Rao, S., C. Bounphanousay, V. Phetpaseuth, K. Kanyavong, B. Sengthong, J.M. Schiller & M.T. Jackson, 1998. Collection and Classification of Lao Rice Germplasm Part 3. Collecting Period—October 1997 to February 1998. Internal report of the National Agricultural Research Center, National Agriculture and Forestry Research Institute, Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry, Vientiane, Lao PDR, and Genetic Resources Center, International Rice Research Institute (IRRI), Los Baños, Philippines.

Jackson, M.T., 1998. Intellectual property rights—the approach of the International Rice Research Institute. Invited paper at the Seminar-Workshop on Plant Patents in Asia Pacific, organized by the Asia & Pacific Seed Association (APSA), held in Manila, Philippines, September 21-22, 1998.

Jackson, M.T., 1998. Recent developments in IPR that have implications for the CGIAR. Invited paper presented at the ICLARM Science Day, International Center for Living Aquatic Resources Management, Manila, Philippines, September 30, 1998.

Jackson, M.T., 1998. The genetics of genetic conservation. Invited paper presented at the Fifth National Genetics Symposium, held at PhilRice, Nueva Ecija, Philippines, December 10-12, 1998.

Jackson, M.T., 1998. The role of the CGIAR’s System-wide Genetic Resources Programme (SGRP) in implementing the GPA. Invited paper presented at the Regional Meeting for Asia and the Pacific to facilitate and promote the implementation of the Global Plan of Action for the Conservation and Sustainable Use of Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture, held in Manila, Philippines, December 15-18, 1998.

Lu, B.R., M.E. Naredo, A.B. Juliano & M.T. Jackson, 1998. Biosystematic studies of the AA genome Oryza species (Poaceae). Poster presented at the Second International Conference on the Comparative Biology of the Monocotyledons and Third International Symposium on Grass Systematics and Evolution, Sydney, Australia, September 27-October 2, 1998.

Morin, S.R., J.L. Pham, M. Calibo, G. Abrigo, D. Erasga, M. Garcia, & M.T. Jackson, 1998. On farm conservation research: assessing rice diversity and indigenous technical knowledge. Invited paper presented at the Workshop on Participatory Plant Breeding, held in New Delhi, March 23-24, 1998.

Morin, S.R., J.L. Pham, M. Calibo, M. Garcia & M.T. Jackson, 1998. Catastrophes and genetic diversity: creating a model of interaction between genebanks and farmers. Paper presented at the FAO meeting on the Global Plan of Action on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture for the Asia-Pacific Region, held in Manila, Philippines, December 15-18, 1998.

1999

Alcantara, A.P., E.B. Guevarra & M.T. Jackson, 1999. The International Rice Genebank Collection Information System. Poster presented at the annual meeting of the Crop Science Society of America, Salt Lake City, October 31-November 4, 1999.

Appa Rao, S., C. Bounphanousay, K. Kanyavong, B. Sengthong, J.M. Schiller & M.T. Jackson, 1999. Collection and classification of Lao rice germplasm, Part 4. Collection Period: September to December 1998. Internal report of the National Agricultural Research Center, National Agriculture and Forestry Research Institute, Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry, Vientiane, Lao PDR, and Genetic Resources Center, International Rice Research Institute (IRRI), Los Baños, Philippines.

Appa Rao, S., C. Bounphanouxay, J.M. Schiller & M.T. Jackson, 1999. Collecting Rice Genetic Resources in the Lao PDR. Poster presented at the annual meeting of the Crop Science Society of America, Salt Lake City, October 31-November 4, 1999.

Jackson, M.T., E.L. Javier & C.G. McLaren, 1999. Rice genetic resources for food security. Invited paper at the IRRI Symposium, held at the annual meeting of the Crop Science Society of America, Salt Lake City, October 31-November 4, 1999.

Jackson, M.T., F.C. de Guzman, R.A. Reaño, M.S.R. Almazan, A.P. Alcantara & E.B. Guevarra, 1999. Managing the world’s largest collection of rice genetic resources. Poster presented at the annual meeting of the Crop Science Society of America, Salt Lake City, October 31-November 4, 1999.

2000

Jackson, M.T., B.R. Lu, M.S. Almazan, M.E. Naredo & A.B. Juliano, 2000. The wild species of rice: conservation and value for rice improvement. Poster presented at the annual meeting of the Crop Science Society of America, Minneapolis, November 5-9, 2000.

Naredo, M.E., A.B. Juliano, M.S. Almazan, B.R. Lu & M.T. Jackson, 2000. Morphological and molecular diversity of AA genome species of rice. Poster presented at the annual meeting of the Crop Science Society of America, Minneapolis, November 5-9, 2000.

Pham J.L., S.R. Morin & M.T. Jackson, 2000. Linking genebanks and participatory conservation and management. Invited paper presented at the International Symposium on The Scientific Basis of Participatory Plant Breeding and Conservation of Genetic Resources, held at Oaxtepec, Morelos, Mexico, October 9-12, 2000.

2001

Jackson, M.T., 2001. Collecting plant genetic resources: partnership or biopiracy. Invited paper presented at the annual meeting of the Crop Science Society of America, Charlotte, North Carolina, October 21-24, 2001.

Jackson, M.T., 2001. Rice: diversity and livelihood for farmers in Asia. Invited paper presented in the symposium Cultural Heritage and Biodiversity, at the annual meeting of the Crop Science Society of America, Charlotte, North Carolina, October 21-24, 2001.

2004

Jackson, M.T., 2004. Achieving the UN Millennium Development Goals begins with rice research. Invited paper presented to the Cross Party International Development Group of the Scottish Parliament, Edinburgh, Scotland, June 2, 2004.

[1] Brian was subsequently appointed Professor of Conservation Genetics at Birmingham, and Deputy Head of the School of Biosciences. He retired almost a decade ago.

John moved to the University of Worcester in 2008 as Professor of Bioscience, and head of of the Institute of Science and the Environment. He is now retired.

[2] Parminder later joined IRRI as a rice breeder, and from there, in the early 2000s, joined the CGIAR’s Harvest Plus program. I believe he has now retired.

[3] When the project ended, Glenn moved to the James Hutton Institute near Dundee, Scotland where he was lead of the potato genetics and breeding group, retiring in July 2023.

Memories. Powerful; fleeting; joyful; or sad. Sometimes, unfortunately, too painful and hidden away in the deepest recesses of the mind, only to be dragged to the surface with great reluctance.

Memories. Powerful; fleeting; joyful; or sad. Sometimes, unfortunately, too painful and hidden away in the deepest recesses of the mind, only to be dragged to the surface with great reluctance.

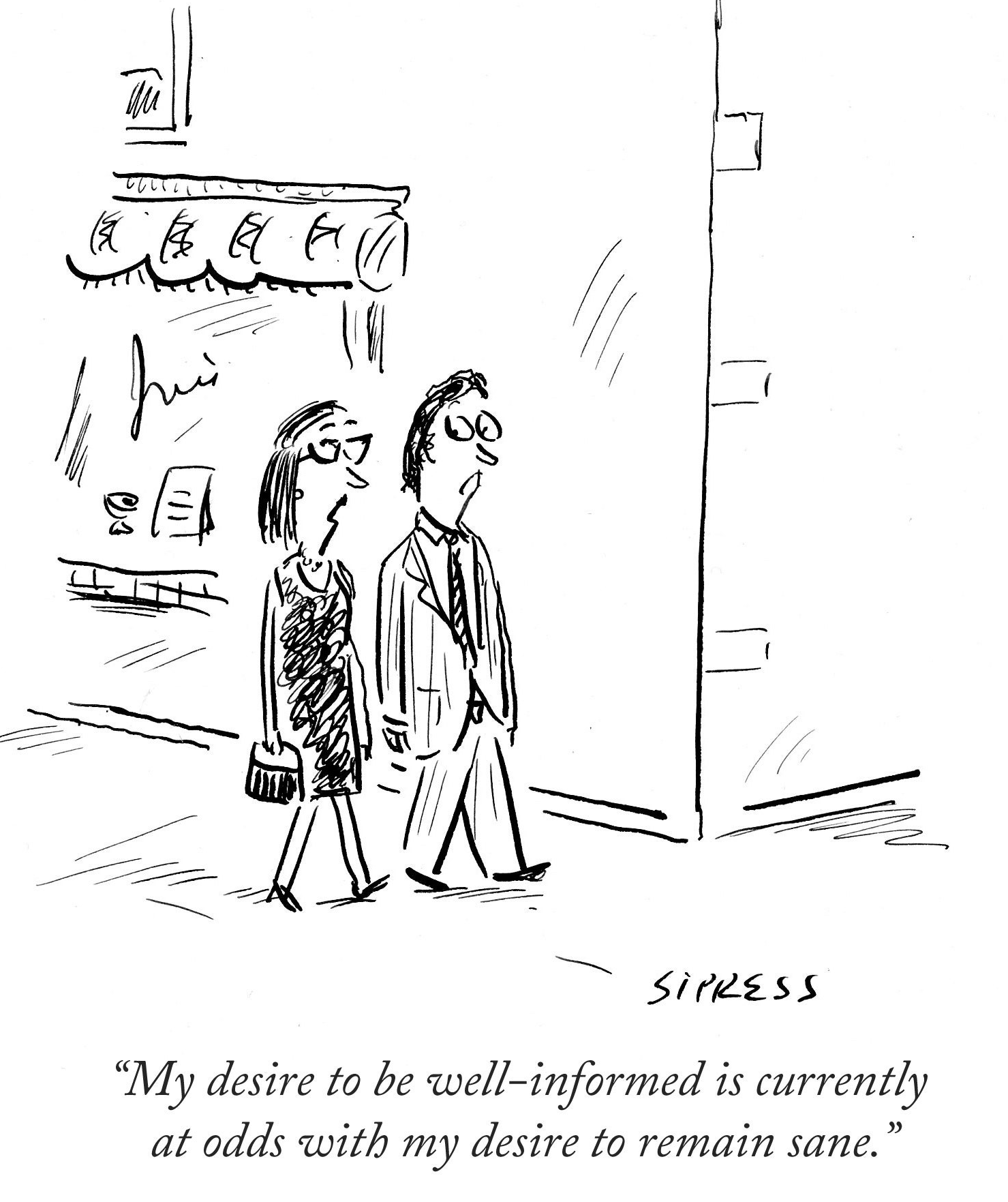

I grew up believing that—despite the suitability or not of the occupant—one should respect the office of a Prime Minister or President.

I grew up believing that—despite the suitability or not of the occupant—one should respect the office of a Prime Minister or President.

And he unleashed mad dogs in the form of Elon Musk and his cohort of employees from the so-called ‘Department for Government Efficiency’ (DOGE) with, it seems, carte blanche authority to do whatever he pleases.

And he unleashed mad dogs in the form of Elon Musk and his cohort of employees from the so-called ‘Department for Government Efficiency’ (DOGE) with, it seems, carte blanche authority to do whatever he pleases.

It was about the

It was about the

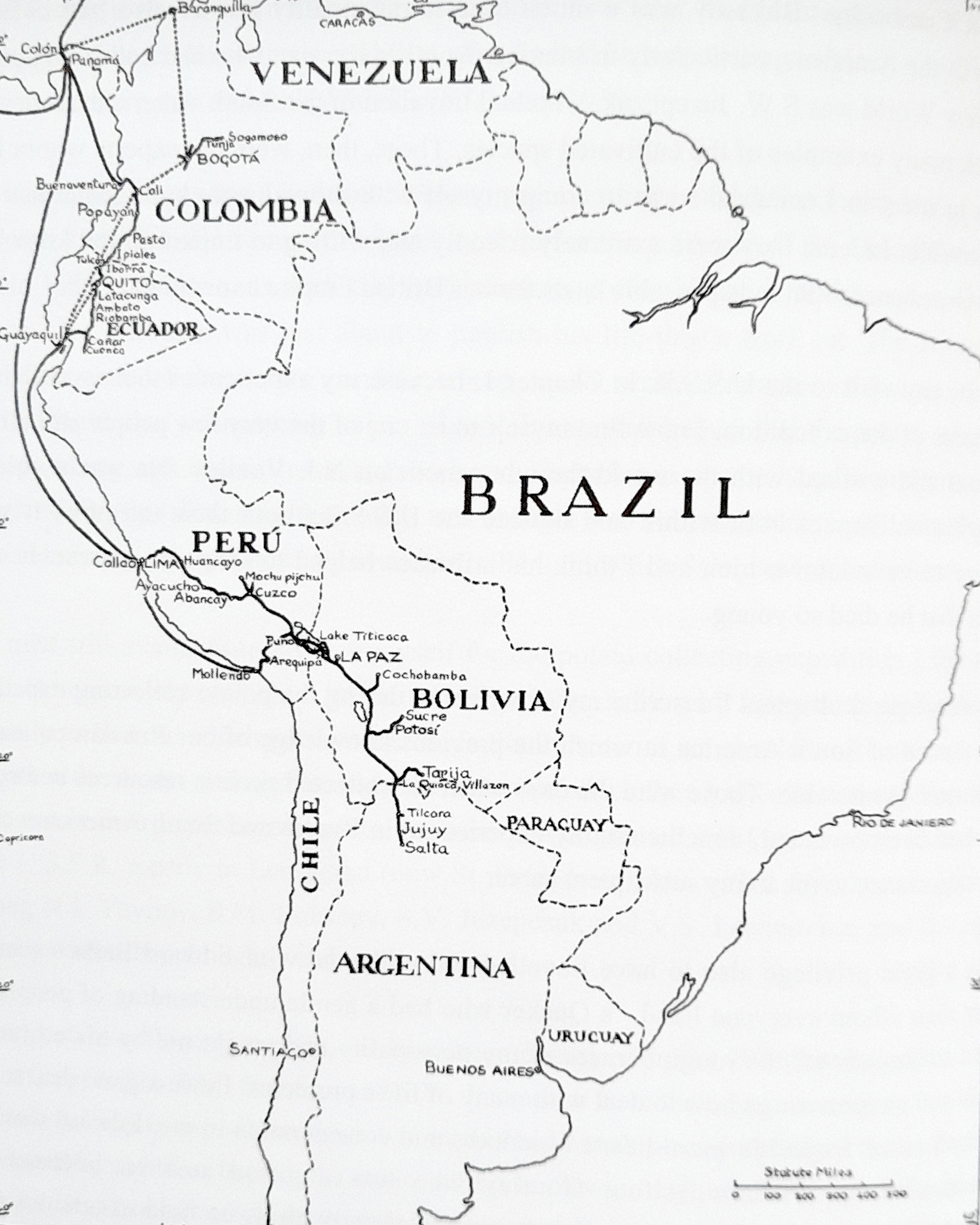

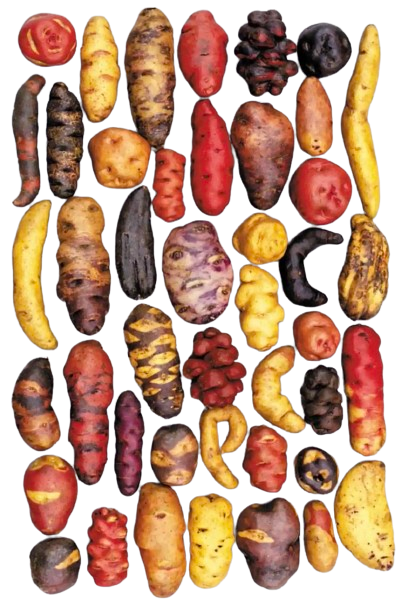

Among the species identified in the course of Jack’s dissertation research was Solanum ballsii from northern Argentina, which he dedicated to EK Balls in a formal description in 1944. However, in his 1963 revised taxonomy of the tuber-bearing Solanums (potatoes), Jack (with his Danish colleague Jens Peter Hjerting, 1917-2012) recognized Solanum ballsii simply as a subspecies of Solanum vernei, a species which has since provided many important sources of resistance to the potato cyst nematode.

Among the species identified in the course of Jack’s dissertation research was Solanum ballsii from northern Argentina, which he dedicated to EK Balls in a formal description in 1944. However, in his 1963 revised taxonomy of the tuber-bearing Solanums (potatoes), Jack (with his Danish colleague Jens Peter Hjerting, 1917-2012) recognized Solanum ballsii simply as a subspecies of Solanum vernei, a species which has since provided many important sources of resistance to the potato cyst nematode.

Before those two concerts it must have been almost 30+ years since I’d attended any live concert, while I was still at university.

Before those two concerts it must have been almost 30+ years since I’d attended any live concert, while I was still at university.

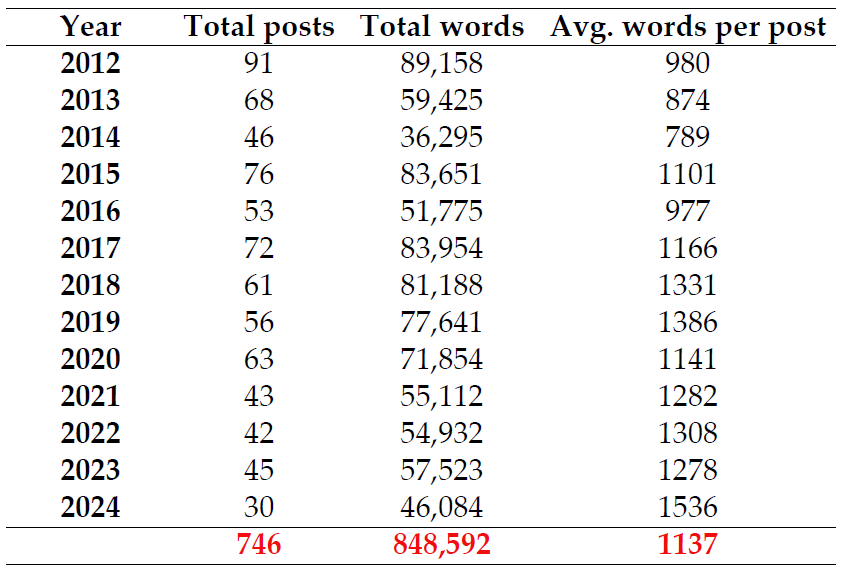

Since I started this blog in February 2012, I have written a number of stories about rice genetic resources and their conservation at the

Since I started this blog in February 2012, I have written a number of stories about rice genetic resources and their conservation at the

During the 1990s, the collection grew by about 30% to a little over 100,000 accessions. This was quite remarkable in itself, given that the

During the 1990s, the collection grew by about 30% to a little over 100,000 accessions. This was quite remarkable in itself, given that the

1991 was a fortuitous time to join IRRI. I was recruited by Director General

1991 was a fortuitous time to join IRRI. I was recruited by Director General

Earlier I mentioned the CBD. There’s no doubt that during the 1990s the whole realm of genetic resources became highly politicized, with the CGIAR centers contributing to CBD discussions as they related to agricultural biodiversity, and through the

Earlier I mentioned the CBD. There’s no doubt that during the 1990s the whole realm of genetic resources became highly politicized, with the CGIAR centers contributing to CBD discussions as they related to agricultural biodiversity, and through the

For many years, Steph and I toyed with becoming members of the

For many years, Steph and I toyed with becoming members of the  We received gift membership of

We received gift membership of  The National Trust was the vision of its

The National Trust was the vision of its

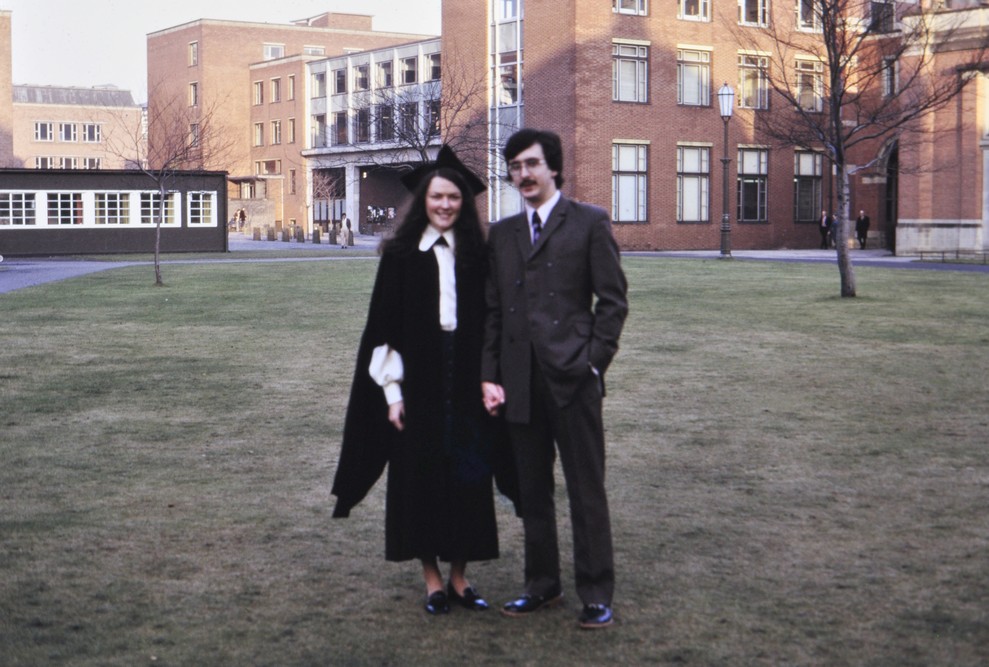

I enjoyed my

I enjoyed my  A third cohort of students arrived in Birmingham in September 1971, among them Stephanie Tribble from Southend-on-Sea who had just graduated from the

A third cohort of students arrived in Birmingham in September 1971, among them Stephanie Tribble from Southend-on-Sea who had just graduated from the

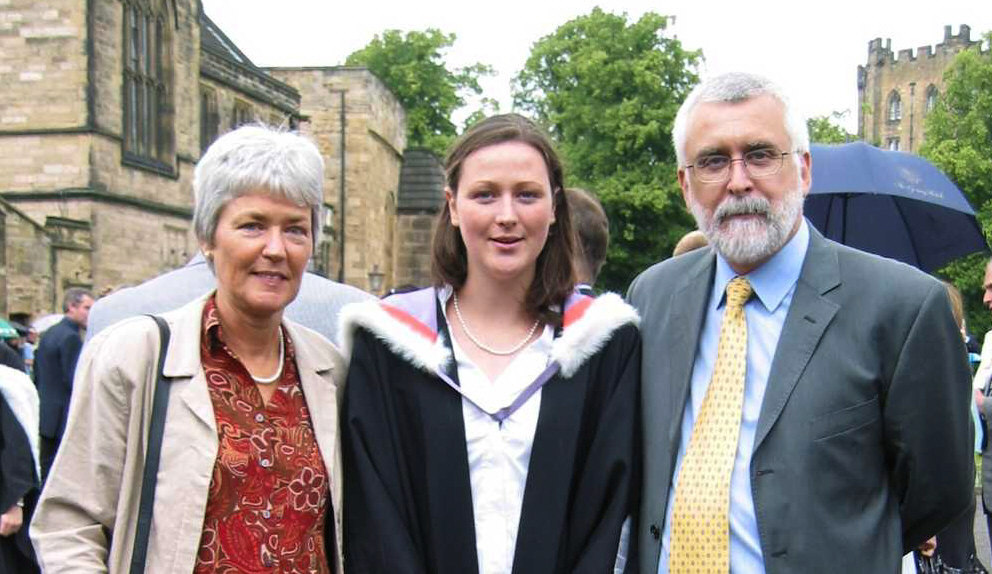

We upended their world when I took the position at IRRI and they moved to the Philippines with Steph just after Christmas 1991. Even more challenging was their enrolment in the

We upended their world when I took the position at IRRI and they moved to the Philippines with Steph just after Christmas 1991. Even more challenging was their enrolment in the  could transfer to

could transfer to

After a gap year, Philippa began her studies in Psychology at

After a gap year, Philippa began her studies in Psychology at

She spent six months looking for a job, finally landing a research assistantship in the

She spent six months looking for a job, finally landing a research assistantship in the

attention as I was reading a book at the time. High brow Muzak.

attention as I was reading a book at the time. High brow Muzak. I was totally unaware of this interesting back story. Nevertheless, it is a beautiful and much appreciated piece of music, that gained position 170/300 in the Classic FM Hall of Fame 2024. Enjoy this interpretation.

I was totally unaware of this interesting back story. Nevertheless, it is a beautiful and much appreciated piece of music, that gained position 170/300 in the Classic FM Hall of Fame 2024. Enjoy this interpretation.

Each Christmas we try to visit one of Trust properties to see their Christmas decorations. And this year it was

Each Christmas we try to visit one of Trust properties to see their Christmas decorations. And this year it was

With some free time in Dublin, I took the opportunity of walking around the city center, and came across a record store on Grafton Street, where this recording of Orfeo ed Euridice was in stock. I also bought Mark Knopfler’s Golden Heart that had just been released. It’s remained a favorite of mine ever since.

With some free time in Dublin, I took the opportunity of walking around the city center, and came across a record store on Grafton Street, where this recording of Orfeo ed Euridice was in stock. I also bought Mark Knopfler’s Golden Heart that had just been released. It’s remained a favorite of mine ever since.

For 20 years before I joined the

For 20 years before I joined the

The CGIAR’s

The CGIAR’s

The next step was to expand the research in Los Baños itself looking at more rice varieties in a real rice-growing environment.

The next step was to expand the research in Los Baños itself looking at more rice varieties in a real rice-growing environment.

Yvette completed her MS degree at the University of the Philippines-Los Baños, co-supervised by me and a faculty member from the university, for a study on two distantly related species, Oryza ridleyi and Oryza longiglumis. Some years later she went on to complete her PhD as well.

Yvette completed her MS degree at the University of the Philippines-Los Baños, co-supervised by me and a faculty member from the university, for a study on two distantly related species, Oryza ridleyi and Oryza longiglumis. Some years later she went on to complete her PhD as well.

In Asia, few collections of rice germplasm had been made in Laos, due to the conflict that had blighted that country over many years. In fact it’s overall capacity for agricultural R&D was quite limited. At the end of the 1980s, and supported with Swiss funding, IRRI opened a country program office in Vientiane (the capital city), headed by the late Dr John Schiller (right), an Australian agronomist who became a good friend.

In Asia, few collections of rice germplasm had been made in Laos, due to the conflict that had blighted that country over many years. In fact it’s overall capacity for agricultural R&D was quite limited. At the end of the 1980s, and supported with Swiss funding, IRRI opened a country program office in Vientiane (the capital city), headed by the late Dr John Schiller (right), an Australian agronomist who became a good friend. Dr Seepana Appa Rao (right, a germplasm scientist) came to us from a sister center, ICRISAT, in Hyderabad, India and he spent five years in Laos, assembling a comprehensive collection of 13,000 Lao rice samples which were duplicated in the International Rice Genebank. I wrote about this special aspect of the rice biodiversity project

Dr Seepana Appa Rao (right, a germplasm scientist) came to us from a sister center, ICRISAT, in Hyderabad, India and he spent five years in Laos, assembling a comprehensive collection of 13,000 Lao rice samples which were duplicated in the International Rice Genebank. I wrote about this special aspect of the rice biodiversity project

My Filipino staff grew in their roles, and the genebank went from strength to strength. I retired just as IRRI reached its Golden Jubilee.

My Filipino staff grew in their roles, and the genebank went from strength to strength. I retired just as IRRI reached its Golden Jubilee.

As I was unpacking my suitcase, I’d turned on the TV, and whatever channel I’d tuned to (my recollection was MTV, but I’ve checked and MTV wasn’t launched until 1981) was broadcasting a rather interesting video, of cartoon hammers marching in step—in the last minute of

As I was unpacking my suitcase, I’d turned on the TV, and whatever channel I’d tuned to (my recollection was MTV, but I’ve checked and MTV wasn’t launched until 1981) was broadcasting a rather interesting video, of cartoon hammers marching in step—in the last minute of  Just yesterday, I came across a video on YouTube, by American YouTube personality, multi-instrumentalist, music producer, and educator,

Just yesterday, I came across a video on YouTube, by American YouTube personality, multi-instrumentalist, music producer, and educator,

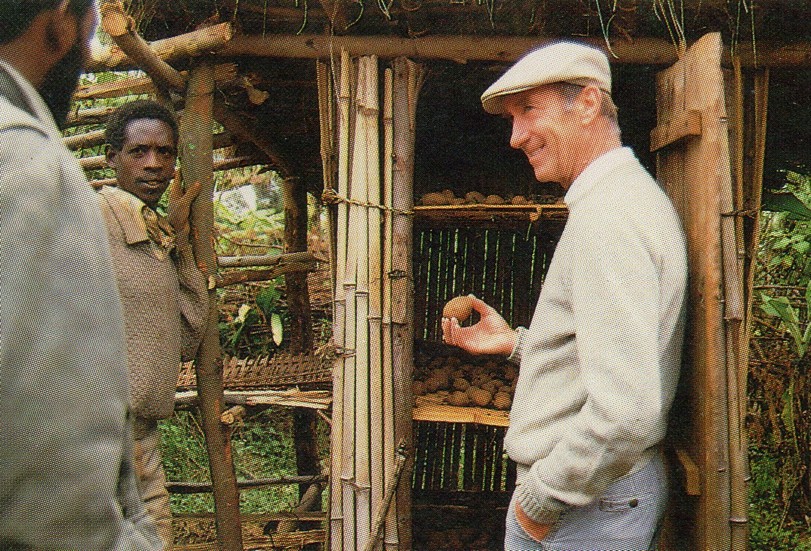

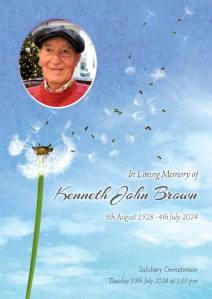

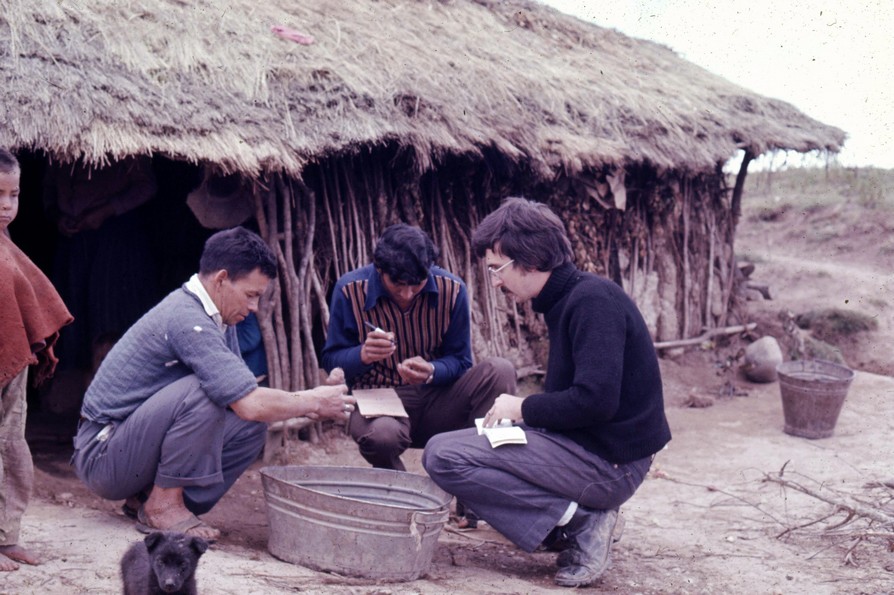

Ken Brown and I first met in February 1976 when he joined the center (known by its Spanish acronym CIP) as Coordinator for Regional Research and Training in the Outreach Program (shortly afterwards renamed Regional Research and Training).

Ken Brown and I first met in February 1976 when he joined the center (known by its Spanish acronym CIP) as Coordinator for Regional Research and Training in the Outreach Program (shortly afterwards renamed Regional Research and Training).

In April 1978, Ken was a member of the team that launched a major regional program in Central America and the Caribbean, perhaps the first consortium among the centers of the

In April 1978, Ken was a member of the team that launched a major regional program in Central America and the Caribbean, perhaps the first consortium among the centers of the

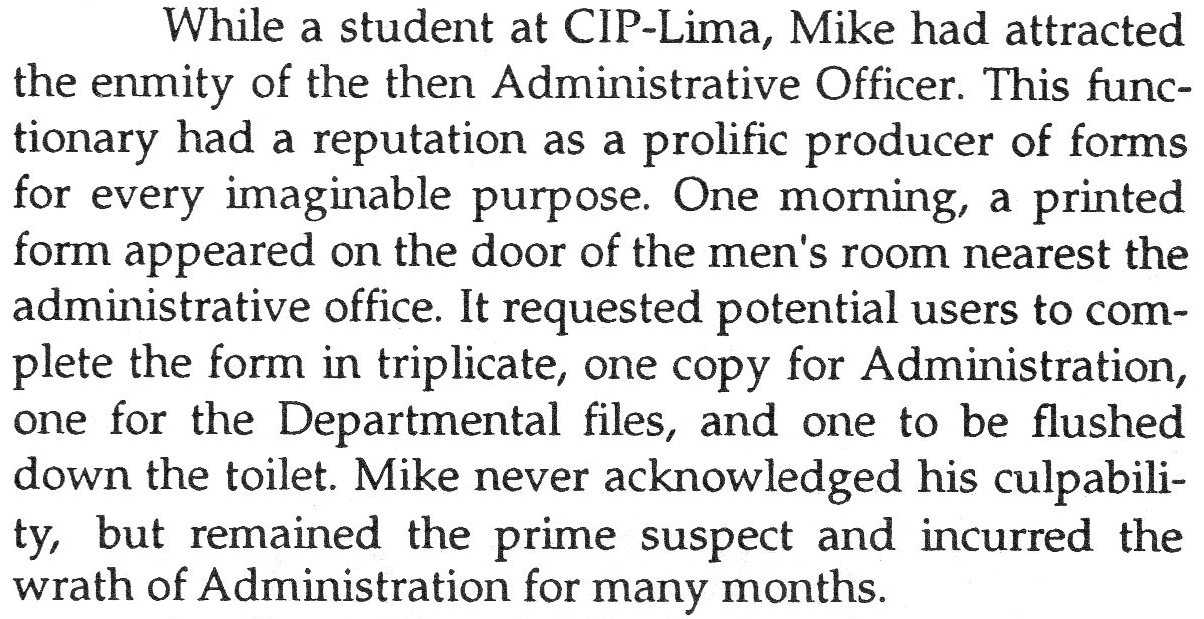

Ken remained at CIP until his retirement around 1993 when he published a short memoir: Roots and Tubers Galore: The Story of CIP’s Global Research Program and the People Who Shaped It.

Ken remained at CIP until his retirement around 1993 when he published a short memoir: Roots and Tubers Galore: The Story of CIP’s Global Research Program and the People Who Shaped It.

I was encouraged (by the wife of a visiting colleague at the agricultural institute where we lived in Turrialba, who was a professor of English Literature at Cornell University) to tackle the novels of Victorian author,

I was encouraged (by the wife of a visiting colleague at the agricultural institute where we lived in Turrialba, who was a professor of English Literature at Cornell University) to tackle the novels of Victorian author,  I also decided to delve into the Wessex novels of

I also decided to delve into the Wessex novels of  In 2017, I spent almost

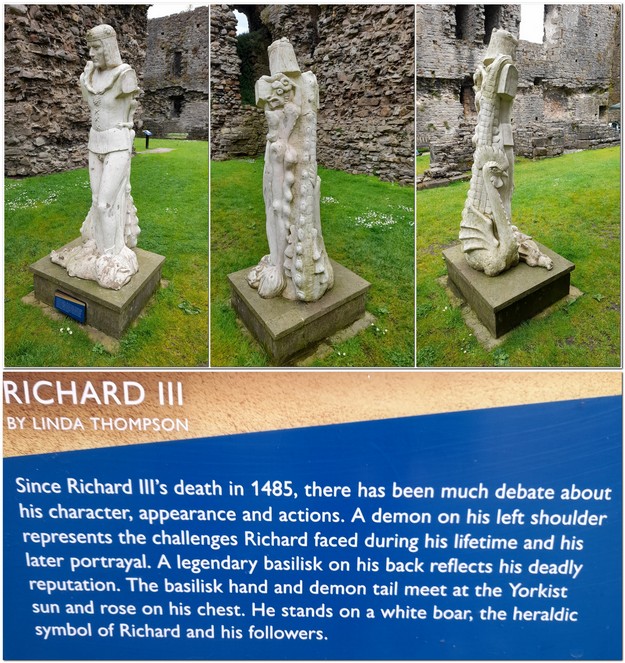

In 2017, I spent almost  But I have taken a fancy to historical novels, some executed better than others. A year or so back, when it was all the rage on TV, I tackled Hilary Mantel’s

But I have taken a fancy to historical novels, some executed better than others. A year or so back, when it was all the rage on TV, I tackled Hilary Mantel’s

I’d joined the

I’d joined the

In October 1975, I successfully defended my PhD thesis (The evolutionary significance of the triploid cultivated potato, Solanum x chaucha Juz. et Buk.) at the University of Birmingham, where my co-supervisor, potato taxonomist and germplasm pioneer

In October 1975, I successfully defended my PhD thesis (The evolutionary significance of the triploid cultivated potato, Solanum x chaucha Juz. et Buk.) at the University of Birmingham, where my co-supervisor, potato taxonomist and germplasm pioneer During my time in Lima, Dr Roger Rowe (left, then head of CIP’s Breeding and Genetics Department) was my local supervisor.

During my time in Lima, Dr Roger Rowe (left, then head of CIP’s Breeding and Genetics Department) was my local supervisor.

I returned to Lima just before the New Year 1976, knowing that CIP’s Director General,

I returned to Lima just before the New Year 1976, knowing that CIP’s Director General,

Plant pathologist Professor Luis Carlos Gonzalez (right, from the University of Costa Rica in San José) and I also studied how to control the disease through a combination of tolerant varieties and soil and weed management.

Plant pathologist Professor Luis Carlos Gonzalez (right, from the University of Costa Rica in San José) and I also studied how to control the disease through a combination of tolerant varieties and soil and weed management.

In 1977,

In 1977,

I can’t finish this section about my time at CIP without mentioning Dr Ken Brown (left), who was head of Regional Research.

I can’t finish this section about my time at CIP without mentioning Dr Ken Brown (left), who was head of Regional Research.

Because of the

Because of the  In the late 1980s, my colleague Brian Ford-Lloyd (right) and I ran a project, funded by KP Agriculture (and managed by my former CIP colleague, Dr John Vessey) to generate

In the late 1980s, my colleague Brian Ford-Lloyd (right) and I ran a project, funded by KP Agriculture (and managed by my former CIP colleague, Dr John Vessey) to generate

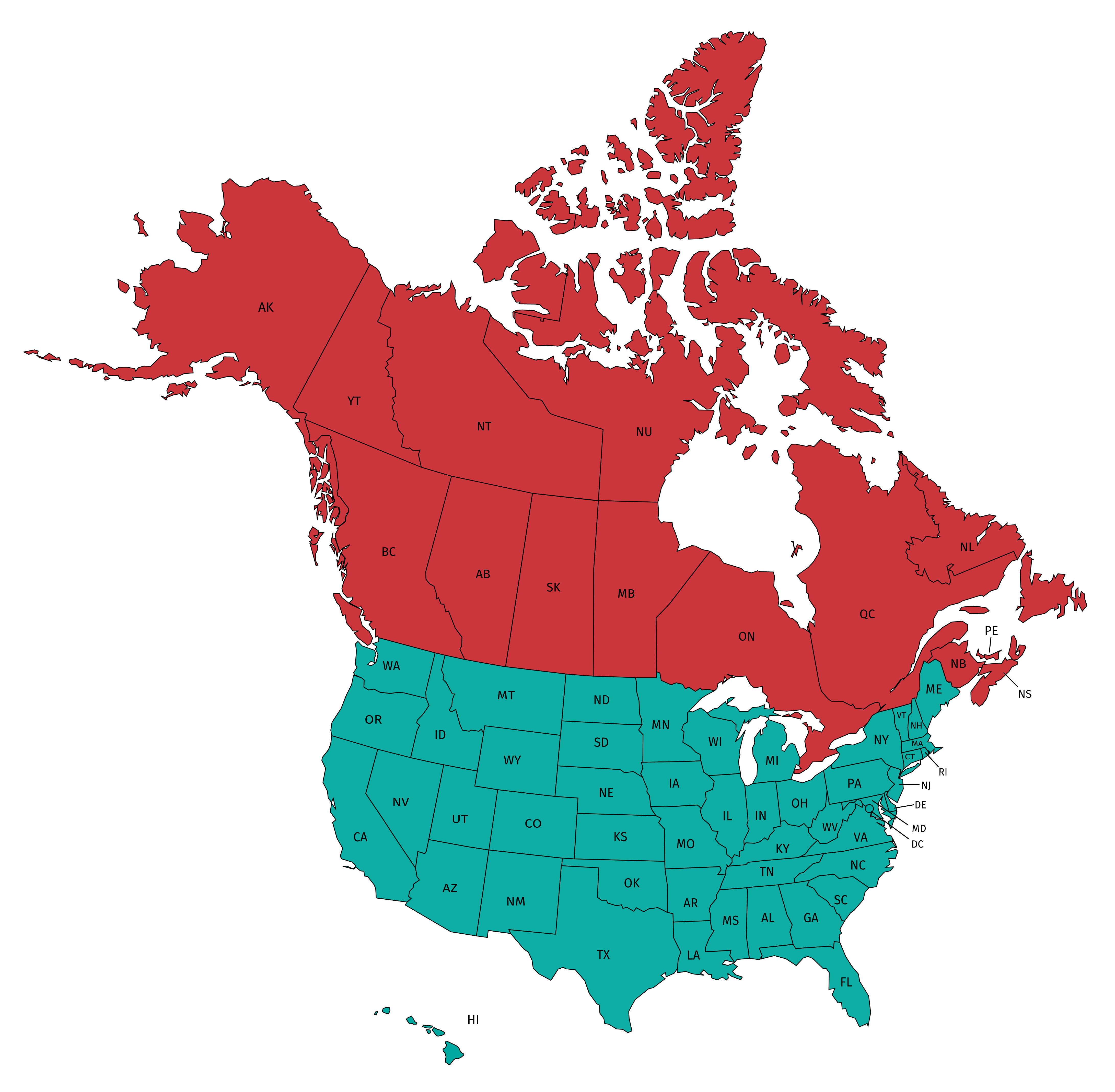

Tuesday 14 May. And here we were preparing to jet off to Las Vegas to begin another trip, this time across Utah and Colorado over the next seven days.

Tuesday 14 May. And here we were preparing to jet off to Las Vegas to begin another trip, this time across Utah and Colorado over the next seven days.

The route we took passed through the

The route we took passed through the

It was surely the influence of one of my mentors,

It was surely the influence of one of my mentors,

Almost immediately after returning to Birmingham, I discovered (by looking through Flora Europaea once again) that the origin of the grasspea, Lathyrus sativus, was unknown. The

Almost immediately after returning to Birmingham, I discovered (by looking through Flora Europaea once again) that the origin of the grasspea, Lathyrus sativus, was unknown. The  The academic year September 1981-September 1982 was my first full year at Birmingham. Among the CUPGR intake was a Malaysian student, Abdul bin Ghani Yunus (right), who asked me to supervise his MSc research project. I persuaded him to tackle a study of variation in the grasspea and its wild relatives, much along the lines I had approached lentil a decade earlier.

The academic year September 1981-September 1982 was my first full year at Birmingham. Among the CUPGR intake was a Malaysian student, Abdul bin Ghani Yunus (right), who asked me to supervise his MSc research project. I persuaded him to tackle a study of variation in the grasspea and its wild relatives, much along the lines I had approached lentil a decade earlier.